The trade in human beings from Africa was a response to external factors. At first, the labour was needed in Portugal, Spain and inAtlantic islands such as Sâo Tome, Cape Verde and the Canaries; then came the period when the Greater Antilles and the Spanish American mainland needed replacements for the Indians who were victims of genocide ; and then the demands of Caribbean and mainland plantation societies had to be met. The records show direct connections between levels of exports from Africa and European demand for slave labour in some part of the American plantation economy. When the Dutch took Pernambuco in Brazil in 1634, the Director of the Dutch West Indian Company immediately informed their agents on the ‘Gold Coast’ that they were to take the necessary steps to pursue the trade in slaves on the adjacent coast east of the Volta — thus creating for that area the infamous name of the ‘Slave Coast.’ When the British West Indian islands took to growing sugar cane, the Gambia was one of the first places to respond. Examples of this kind of external control can be instanced right up to the end of the trade, and this embraces Eastern Africa also, since European markets in the Indian Ocean islands became important in the 18th and 19th centuries, and since demand in places like Brazil caused Mozambicans to be shipped round the Cape of Good Hope.Throughout the 17th and 18th centuries, and for most of the 19th century, the exploitation of Africa and African labour continued to be a source for the accumulation o capital to be re-invested in Western Europe. The African contribution to European capitalist growth extended over such vital sectors as shipping, insurance, the formation companies, capitalist agriculture, technology and the manufacture of machinery. The effects were so wide-ranging that many are seldom brought to the notice of the reading public (Source: How Europe Underdeveloped Africa).

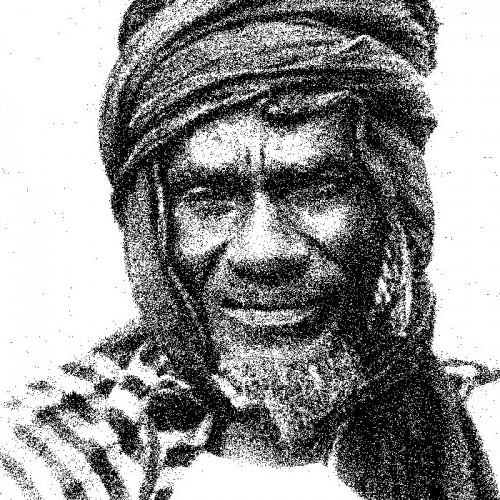

Samory Toure: African Napoleon and Muslim Revolutionary Leader

Samory Toure: African Napoleon and Muslim Revolutionary Leader