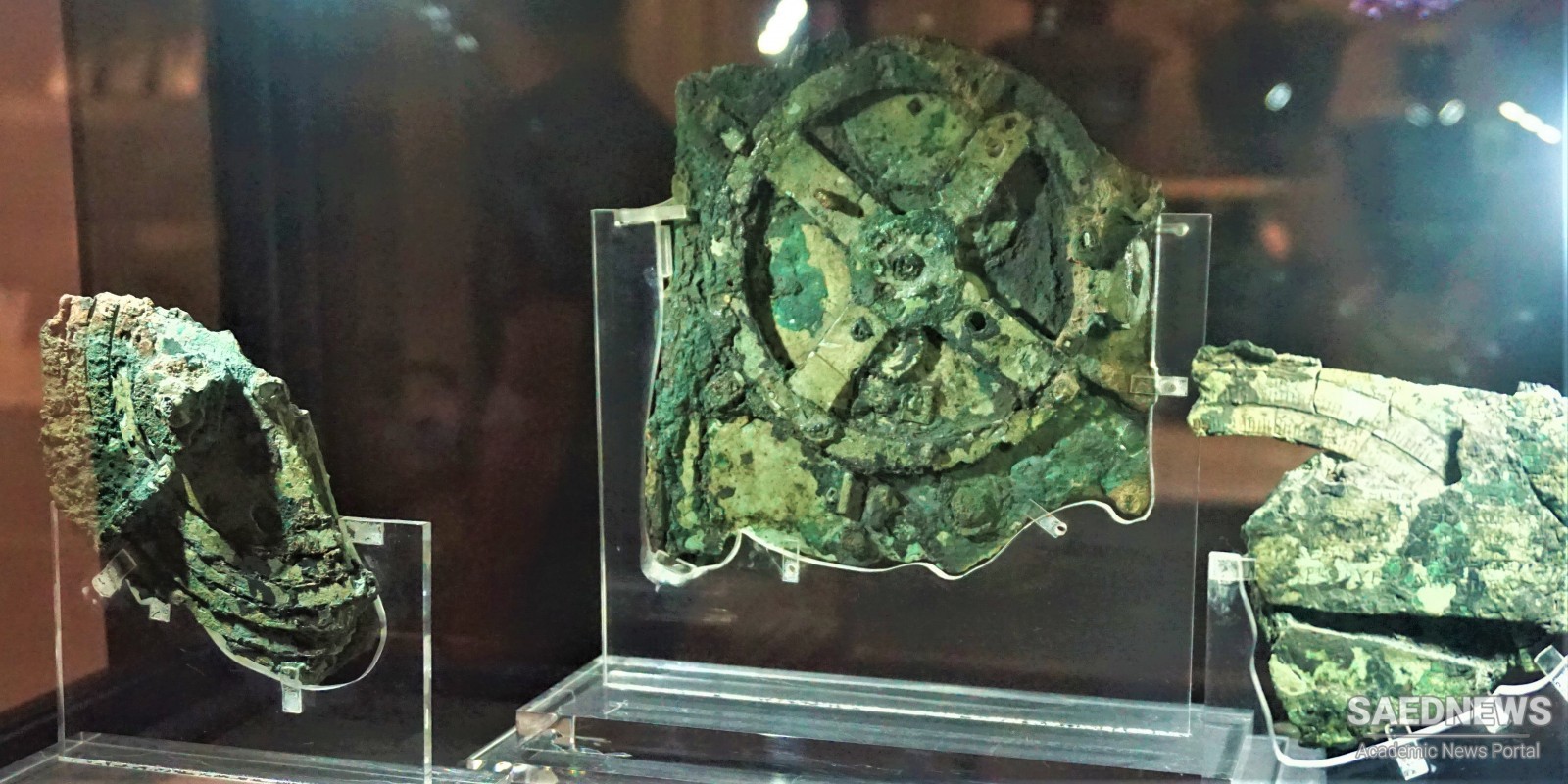

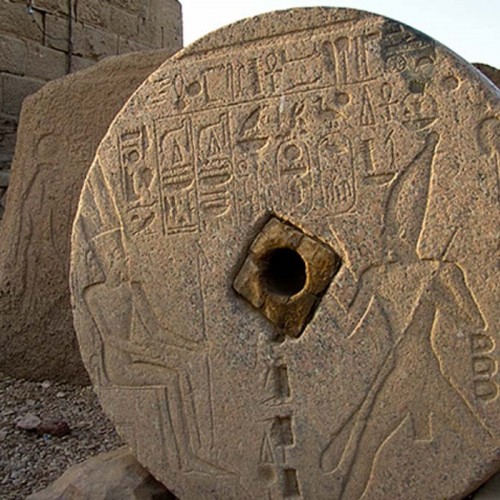

It was in part thanks to the toothed gear, a revolutionary device that could change the direction of power and increase or decrease the speed of movement, that in the Hellenistic and Roman periods the water wheel was used both as a lifting device and to power other kinds of machines like mills and (at the end of the ancient world) even saws. It was the Hellenistic Greeks, too, who invented the water pump with automatic inlet and outlet valves. Still, it remained for humans and animals to power most of the machines of antiquity: animal-powered mills, for example, are always more common than their water-powered cousins. Perhaps the single most remarkable example of the ancients’ skill in designing machines based on these basic mechanical principles is the now-famous Antikythera mechanism. Just over a hundred years ago, sponge fishermen working in the waters off an islet near the Greek island of Kythera discovered an ancient shipwreck, and hauled up from it (among other things) an encrusted mass of bronze. This unprepossessing discovery was to prove to be a late-Hellenistic instrument that, through an intricate system of gears and dials, allowed complex calculations of data apparently related to the solar and lunar calendars. Understandably, this bit of ancient high technology is often identified as the primitive ancestor of our modern computer. This is a bit of a simplification, since the gears of the mechanism bear a greater relationship to Renaissance mechanical astrolabes and clockworks than to the binary system on which our computers are based. But the device remains one of the most intriguing and advanced applications of mechanical theory in antiquity (Source: Ancient Technology).

Ancient Technological Wonders: Struggle for Facilitation of Social Life

Ancient Technological Wonders: Struggle for Facilitation of Social Life