Drastic critique of the Islamic past, it can be argued, could have occurred only in a milieu impregnated with heterodoxy. Kermani was not a conventional Babi loyal to the messianic precepts and its proto-shari‘a system devised by the Bab in his Bayan, even though for a while he did remain loyal to the Azali activist brand of Babism and a passionate supporter of the Azali sectarian battles against the Baha’is. Yet the Babi past served Kermani as an intellectual springboard to come to terms with European modernity. His intellectual profile included not only the European Enlightenment but also a complex amalgam of materialist philosophy, socialist political programs, and nationalism with a chauvinist bent. It was the renewed subversion against the Qajar state, however, that in 1896 cost Kermani his life, when he and two of his cohorts were arrested and detained by order of the Sultan ‘Abd al-Hamid, who seems to have been alerted of an anti-Qajar conspiracy in the making. After the assassination of Naser al-Din Shah, they were duly extradited to Iran as accomplices and executed in Tabriz by the order of then crown prince Mohammad ‘Ali Mirza (1872– 1925). Whatever Kermani’s role, it was his memory as an anti-Qajar dissident that elevated him to the status of a martyr in the narrative of the Constitutional Revolution. An unabashed critic of all organized religions, and especially Islam, he advocated a rationalistic view of civilization that was the closest a nineteenth-century Iranian expatriate could come to the Deist ideas of the French Enlightenment (albeit via Russian literature). The chief vehicle for this social and moral critique was modern European theater, a medium new to the Iranian (and Azarbaijani) audience. Even though Akhundzadeh’s plays were published abroad and enjoyed a sizable readership in their original Turkish and later in Persian translation, they were hardly ever performed. A major theme in Akhundzadeh’s works, inspired by the simplicity of Molière’s plays, was the contrast between the hold of old beliefs and practices, the “superstitions,” in Muslim societies and the potency of modern civilizational forces, especially the modern sciences and medicine.

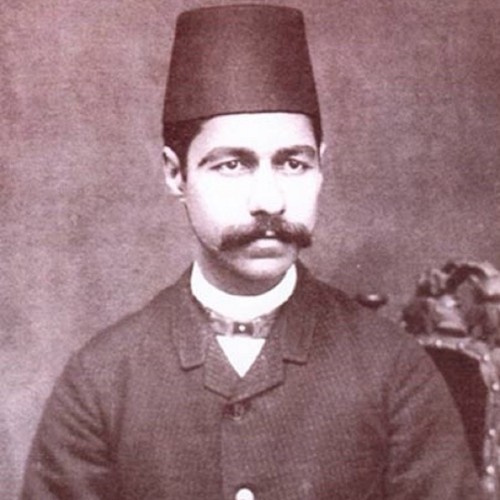

Mirza Aqa Khan Kermani and Modern Nationalism in Iran

Mirza Aqa Khan Kermani and Modern Nationalism in Iran