The Bakhtiyaris of central and southwestern Iran, arguably the largest confederacy in the country, were an odd candidate to support Tabriz, since a few detachments of Bakhtiyari horsemen were among the government troops fighting in Tabriz. Yet a rival faction in the Bakhtiyari leadership turned in favor of the constitutionalists.

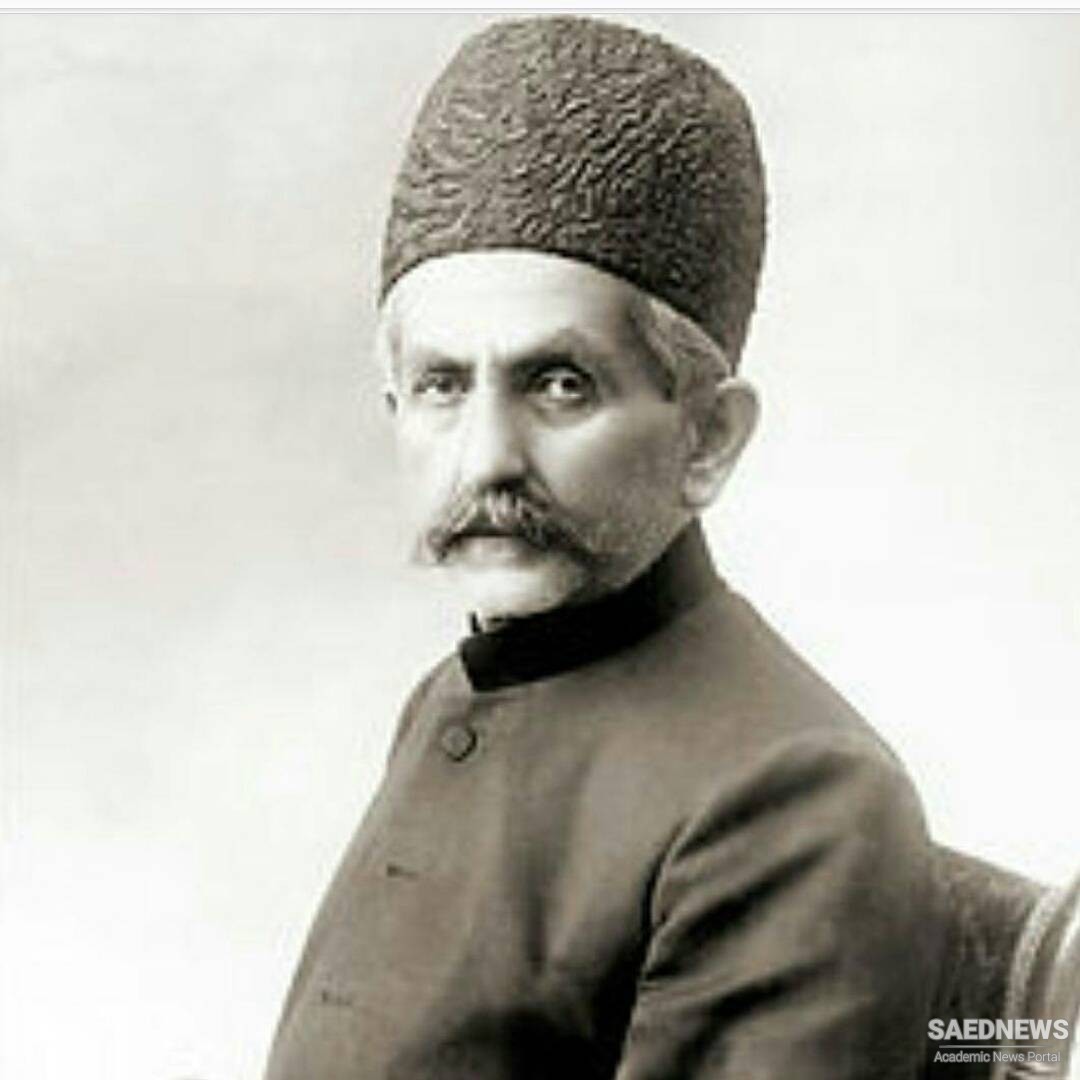

It was headed by ‘Ali-Qoli Khan Sardar As‘ad (1856–1917), a cultivated khan with nationalist predilections whose interest in Iranian history, and that of his own tribe, along with his previous residence in Europe, had converted him into a liberal nationalist of some valor. Beginning early in 1909, the Bakhtiyari horsemen under his command, well equipped by standards of the time, were a formidable force in the south of the country.

Unlike the constitutionalist fighters in the Tabriz wards, they enjoyed the freedom of the steppes and nomadic mobility, which allowed them to capture Isfahan with relative ease. Sardar As‘ad was successful in forging a semblance of unity among the khans of his tribe’s major league. That the Bakhtiyari lands happened to be where oil was first discovered in Iran, as early as 1908, was not entirely irrelevant to the future prominence of this tribe in national politics. In 1909, however, the issue of oil and British dealings with the Bakhtiyaris were not yet a factor.

The call for a concerted march to Tehran first came from the fighters in Rasht, where an assortment of Caucasian social democrats and Armenian volunteers, arriving in Russian vessels via the Caspian, joined hands with the Rasht fighters for control of the provincial center. They came to be known as Melliyun (nationalists).

As with the Bakhtiyaris, here, too, a major local dignitary, Gholam-Hosain Khan Tonekaboni, later known as Sepahdar, and some of his allies among the landowning classes of prosperous Gilan province, shifted their loyalties from Tehran to the nationalists’ side. Sepahdar, who earlier had fought with his troops against the Tabriz resistance, reappeared in a new nationalist guise. His rise to prominence denoted the dawn of a provincial landowning class that would come to play a major role in the politics of the postrevolutionary era.

Despite the despair and uncertainty of the moment, there was an air of optimism for constitutional restoration, and even though radical elements vowed to remove Mohammad ‘Ali Shah, there was a fair amount of support for compromise as well. This virtual telegraphic community in Iran, for they primarily communicated through telegraphic messages, was defiant toward elements within the Tehran court, and in that they found themselves in a surprising accord with the two neighboring powers.

In April 1909 a strongly worded Anglo-Russian memorandum warned the shah that unless he restored the constitution and removed its enemies from his court, he stood to lose the two powers’ already-sinking confidence in him—a warning that appeared to the shah’s opposition as a green light to capture Tehran. In reality, it was meant to encourage the shah to restore some semblance of a constitutional regime in order to stop the constitutionalists’ advances.

Brave and Proud Tabriz: United to Defend the Moribund Rule of Law

Brave and Proud Tabriz: United to Defend the Moribund Rule of Law