In truth, however, the Negro abolition societies did not reflect a go-it-alone philosophy on the part of the founders. Doubtless some of them had felt that they would be more at ease and under less of a strain in a racially separate group. Others may have preferred for the time a Negro society in order to spare their white abolitionist colleagues any embarrassment or hostility that their presence might incur. But whatever their reason, the founders of Negro societies did not envision their efforts as distinctive or self-contained; rather they viewed their role as that of a true auxiliary—supportive, supplemental, and subsidiary. Negro abolitionists spoke with the same accents as their white counterparts, although perhaps in a voice of differing pitch.

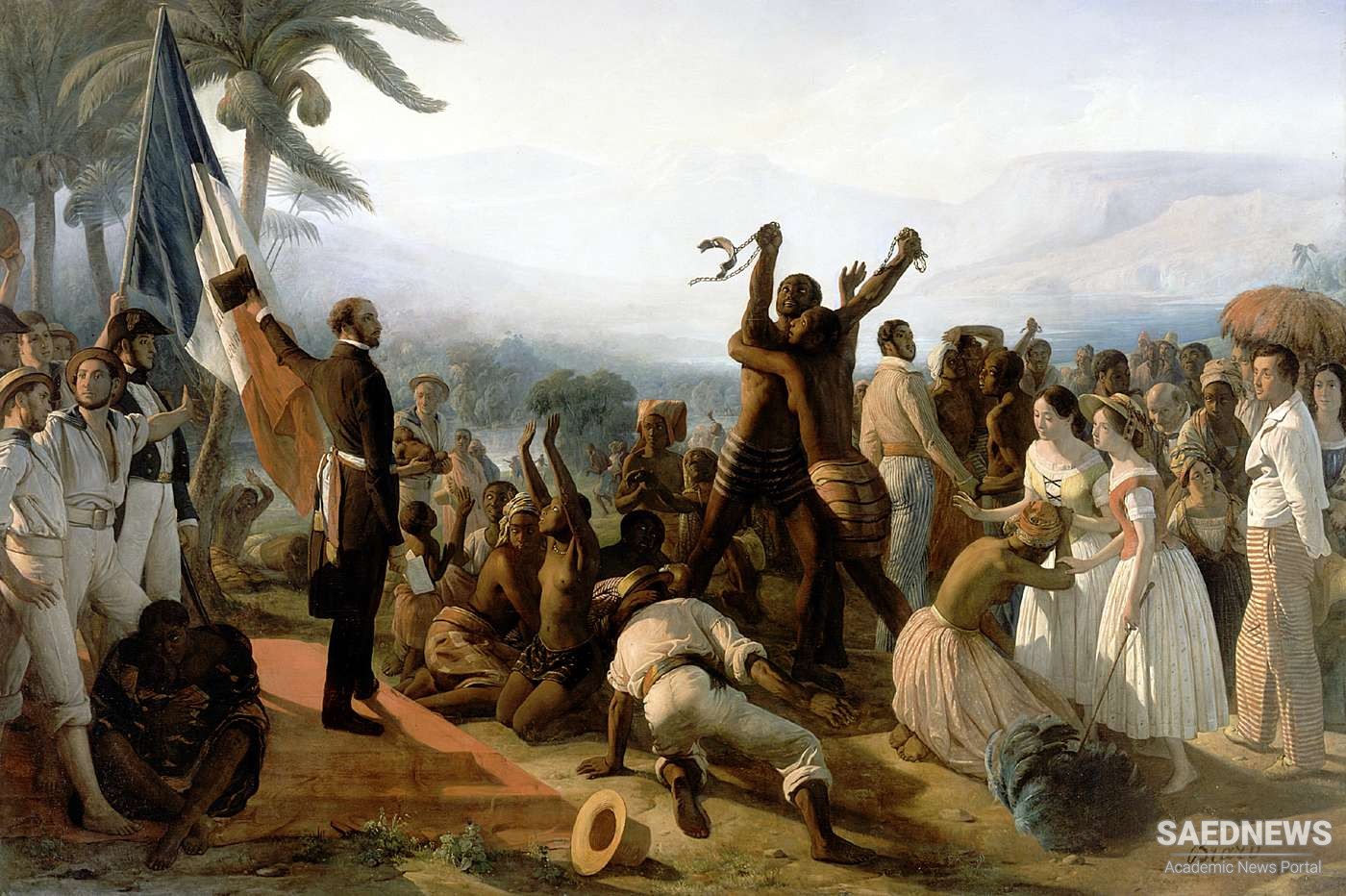

Negro participants, fittingly enough perhaps, formed a more integral component of the abolition crusade than of any other major reform in America. The larger and far more influential body of Negro abolitionists who never joined a col- ored antislavery society would, as a natural consequence, work closely with whites. But much the same was true for members of the Negro societies, which in their outlook and operations were closely tied in to the larger movement. This reciprocal, interlocking relationship between black and white reformers may be demonstrated by the support, financial and otherwise, each gave to the other in pursuit of the common goal.

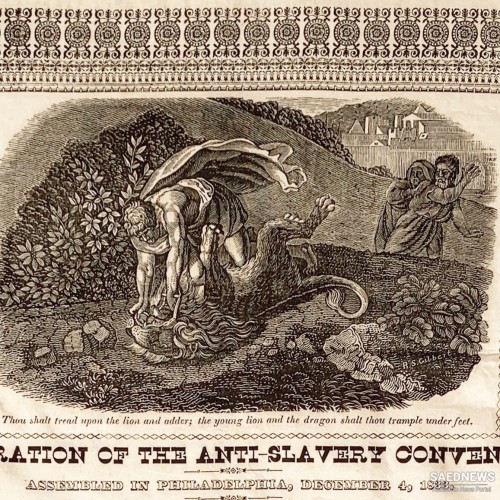

American Anti-Slavery Society: Civil Efforts towards Abolitionism

American Anti-Slavery Society: Civil Efforts towards Abolitionism