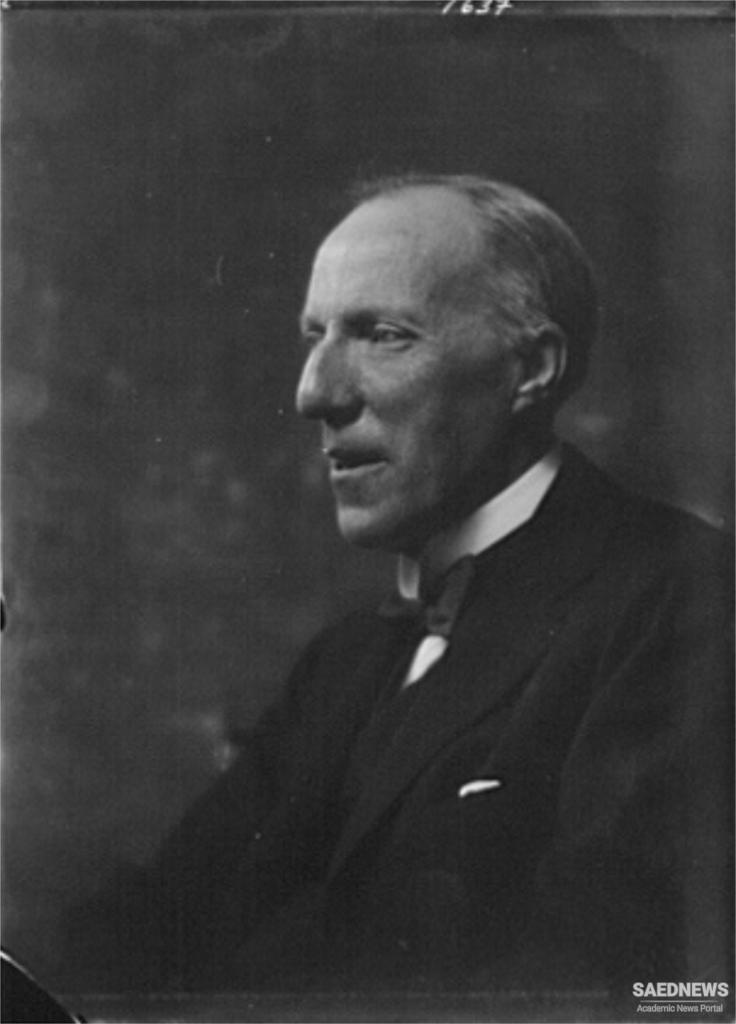

Cecil Sharp instigated the “first English folk revival” in the early years of the twentieth century in several ways: intensive collecting in rural England, the publication of a seminal study (English Folk Song: Some Conclusions, 1907), the propagation of songbooks for schools and the public, the revitalization of Morris dancing, and the founding of the English Folk Song Society (1911). Sharp’s work persuaded the composer Ralph Vaughan Williams, among others, to use folk song in his concert works.

Sharp made a pilgrimage to the United States in 1912–14 to follow the trail of English folk song to Appalachia, building on the budding collecting he found there. He produced a groundbreaking two-volume work, English Folk-Songs from the Southern Appalachians (1932), that viewed the American southeastern mountaineers as an untouched sanctuary of “organic” living and singing. A leftist critique of Sharp as a bourgeois, prudish nationalist took hold in the 1970s, changing academic opinion about this foundational fi gure whose work nevertheless remains a cornerstone of folk song research in both Britain and the United States.

In the United States, folk music defi nition split along the racial lines of the 1800s. For Americans, indigenous peoples took the place of European “primitive,” their “savagery” eventually tinged with sentimentality as the tribes were pacifi ed and thus “doomed to vanish.” The quest for Native American folklore became one of the main goals for the new American Folklore Society, defined as collecting “the fast-vanishing remains of folklore in America,” with a tilt toward American Indian material. The very fi rst doctoral dissertation in musicology written by an American on any music research topic was penned by Theodore Baker in 1882 and titled “On the Music of the North American Savages.” Baker had to go to the University of Leipzig in Germany to do his degree work.

Meanwhile, African American music, originally part of the experience of slavery, remained in a “peculiar” position. It could not exactly be “folk music,” which belonged to the rural white majority. Cecil Sharp, the great English folk music activist, came to Appalachia in 1912. He was hoping to fi nd preserved remnants of old English folk song. He did a great job of collecting the melodies of the mountains at a time when Americans were just beginning to take them seriously. But he scrupulously ignored any ties to the black musics also indigenous to the region.

He said that the white highlanders had “one and all entered at birth into the full enjoyment of their racial heritage,” creating a “community in which singing was as common and almost as universal a practice as speaking.” Yet in Sharp’s day, it was on urban stages that the average American consumed a large amount of so-called black folk music, as parodied and re-created by white performers in blackface in the most popular form of the nineteenth century, the “minstrel show,” and offshoots of those productions, such as the medicine show, reached more isolated places reasonably quickly.

Music the New Platform of Preaching

Music the New Platform of Preaching