There are now at least two schemes of chronology for the early Sasanians, both of which are plausible. It is impossible to discuss here the vast literature relating to such questions as the difference between accession to the throne and coronation, the Babylonian practice of counting the accession year from new year's day, the death of Mani, and the like. Fortunately, the two positions have been well summarized by their two major proponents, S. H. Taqizadeh and W. B. Henning.

A difference of three years exists throughout. The discovery of a Greek codex on the life of Man! seems to resolve this discrepancy, but problems still remain. The relevant passage in the codex reads as follows: When I became twenty-four years old, in the year in which the Persian king Dari-Ardashir conquered the city of Hatra, and in which King Shapur, his son, put on the greatest diadem [was crowned] in the month of Pharmuthi, on the day of the moon, my most blessed Lord took compassion on me, summoned me to his grace [etc.]

The Egyptian month and year can be calculated to show that the crowning of Shapur as co-ruler with his father must have taken place on 12 April 240 (first of the Babylonian month Nisan 551). The co-regency of Shapur and Ardashir seems to have lasted until early in 242. Thus we have a problem that Shapur may have had two "crownings", one as co-regent in 240 and another as sole ruler in 243, although it is more likely that there was only one crowning in 240.

After Ardashir overthrew Ardavan, his task of conquest was not ended. The great Parthian feudal families, if one may use the word "feudal" in its widest connotation, either submitted to Ardashir. willingly or unwillingly, or they were in turn defeated. The family of the Karen, with their centre probably at Nihavand, is said to have been almost exterminated save one member who fled to Armenia and founded the Kamsarakan noble family, according to an Armenian source.1 Khosrov, the Arsacid king of Armenia, certainly led an opposition to Ardashir, and Armenian tradition has it that his relative the Kushan king Vehsadjan (Vasudeva ?) supported him, whereas the Suren and other noble Iranian families submitted to Ardashir. Members of the Karen family, however, appear high on the list of notables at the court of Ardashir, as recorded in the great inscription of Shapur I, which contradicts the notice in the Armenian source above. Therefore, we may assume that gradually most of the great lords, including the Karen, joined Ardashir.

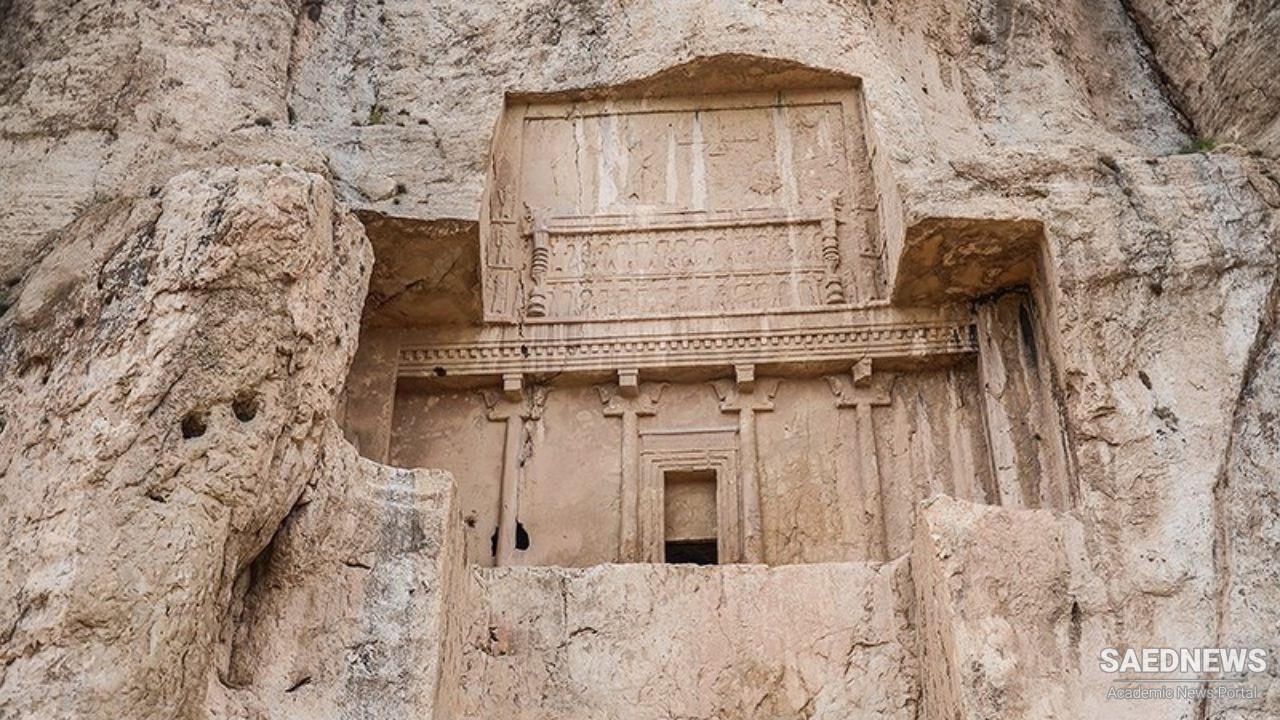

In some areas, Ardashir installed sub-kings from his own family as rulers. Thus one son, also called Ardashir, was made king of Kirman.3 Other sons were probably installed elsewhere, and Persian governors or other officials were sent to the principalities which had submitted. Governors and kings, who were members of the Sasanian family, were shifted from one area to another according to policy or need. Although there is no evidence that Ardashir had any detailed and clear knowledge of the Achaemenians, the fact that he and his son Shapur carved rock-reliefs near their Achaemenian counterparts at Naqsh-i Rustam indicates a policy of cultural as well as political aggrandizement in imitation of the past. Several Roman historians assert that Ardashir consciously planned to re-establish the Achaemenian empire, and there is no reason to doubt the intention of the founder of the dynasty to create a vast empire.

The rise of the Sasanian dynasty

The rise of the Sasanian dynasty