The Constitutional Revolution had a mixed legacy for Iran. To begin with, it is unclear whether the participants in the movement to impose constitutional restrictions on the monarchy—the clergy, members of the intelligentsia, local notables, and bazaar merchants—ever considered themselves “revolutionaries” per se. They neither sought to nor were able to overthrow the existing political order and replace it with a fundamentally different one. Instead, insofar as the movement’s principal actors were concerned, they had embarked on a quest to bring about a government that would be in compliance with traditional notions of justice (‘edalat) and freedom from tyranny (zulm). In the long run, they failed. In the process, the movement gave rise to a number of local associations (anjomans), especially in Tehran and the northern city of Tabriz. Inspired by and modeled after the communist soviets, the associations were meant to choose local deputies for the Majles and to take an active role in local government. However, they had the unintended consequence of deepening existing factional divisions and greatly contributing to the country’s administrative paralysis. And, as if to add insult to injury, the two great powers, Britain and Russia, only found Iran’s chaotic circumstances more conducive to their larger imperial goals and expanded their presence and hold over the country.

Despite its multiple setbacks and negative consequences, the Constitutional Revolution turned out to be one of the most important events in Iranian history. Later generations of Iranians pointed to the “revolutionary” years of 1905–11 as the beginning of a long and protracted struggle to curtail the arbitrary powers of absolutist monarchy. Also, both the constitution (Qanun Asasi, or Basic Law) and the Majles were important political innovations for Iran, their foreign and imported nature notwithstanding. While in the early decades the Majles was politically emasculated and ceased to function as a meaningful parliamentary body, in the aftermath of the Second World War, when the Iranian monarchy was once again weakened, it did make its imprint on Iranian history. Finally, the same set of actors involved in the Constitutional Revolution went on to bring about a different sort of revolution some seven decades later—the Islamic revolution of 1978–79— this time with significant help from the urban middle classes.

In the short run, however, the Constitutional Revolution plunged Iran into chaos. With an ineffectual monarchy and the Majles torn by factional rivalries, the country drifted through the Great War at the mercy of foreign powers. Finally, in 1921, an army officer named Reza and a well-known journalist by the name of Seyyed Zia-alddin Tabatabai launched a military coup, becoming the commander of the army and the prime minister, respectively. Zia was eased out of power in 1923, and Reza deposed the monarchy two years later, thus bringing the Qajar era to an end. Having earlier adopted the last name Pahlavi, he declared himself shah and established the Pahlavi dynasty.

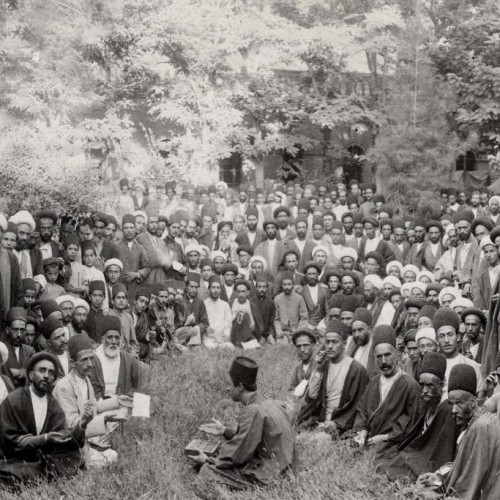

British Embassy the Sanctuary of the Constitutional Activists!

British Embassy the Sanctuary of the Constitutional Activists!