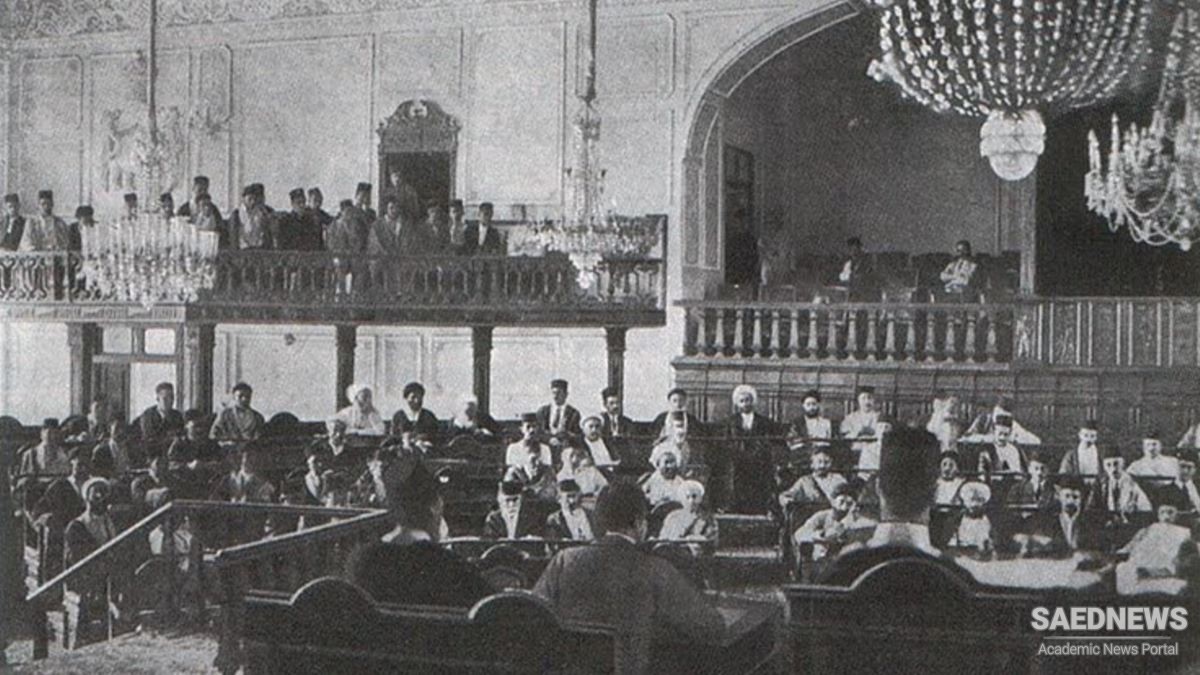

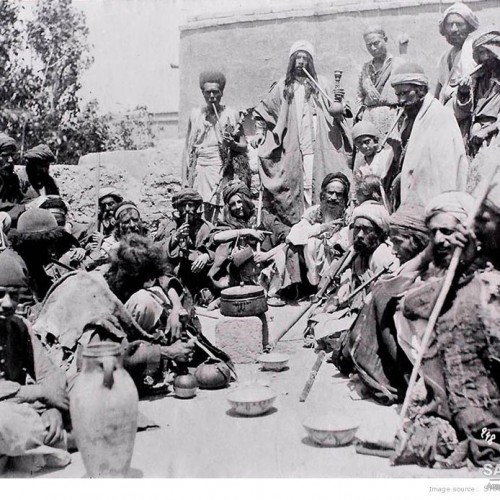

The Friday Mosque Incident marked the beginning of a popular movement that eventually came to be recognized as the Constitutional Revolution (Enqelab-e Mashruteh), a transformational experience with major consequences for twentieth-century Iran. The previously described episode highlights most, if not all, of the elements that would shape the revolution: merchants and artisans resentful of an inefficient and intrusive state; the lower- and middle-ranking mullahs of various shades calling on the mojtaheds to come out in support of the people; the Qajar state’s desperate reactions to demands for popular participation and eventually for a constitution; and finally, the urban population in large numbers. To these groups were added in due course the Western-educated elite, who joined the indigenous radical elements and helped shape the parliament (Majles) and frame the modern constitution.The emerging constitutional movement, with its distinctive pluralistic features that allowed for diverse social and political groups to participate, however, soon ran counter to a royalist front that, backed by imperial Russia, aimed to reassert the power of an autocratic Qajar shah in power and preserve the privileges of the ruling elite. The revolution also contested the privileges of the very clerical class that first came to its support but soon changed course as the constitution and the Majles imposed limits on the mojtaheds’ sphere of authority and defined the boundaries of the shari‘a. The outcome was a multifaceted struggle that helped define Iran’s modern national identity, emerging first in the civil war of 1908–1909 and continuing in the two decades before the rise of Reza Shah and the establishment of the Pahlavi order in 1925 (Source: Iran a Modern History).

Constitutionalism and Constitutional Movement: Beginning of Modern History of Persia

Constitutionalism and Constitutional Movement: Beginning of Modern History of Persia