There is a composite artistic construction at play, combining traditional Persian compositions and European stylistic techniques, which seems to produce an altogether new style of painting. The development is better understood through a comparison between the wall paintings of the Chehel Sotun and Ali Qapu palaces. The wall paintings of the Ali Qapu palace, made half a century before those of Chehel Sotun, were probably produced by the court master painter Reza Abbasi, or under his supervision, and all follow the idealistic style of Persian miniatures, showing none of the influence of the naturalistic paintings of the Chehel Sotun Palace. This generation of artists, however, did produce paintings of Europeans, wearing foreign costume, such as black hats and ruffs, as may be seen in the Ali Qapu murals and the single-page paintings of Reza Abbasi and his contemporaries.

The Chehel Sotun Palace was completed in 1647 by Shah Abbas II, providing a venue in which he could receive guests. It is not known which artists are responsible for the wall paintings of this palace. The style of some of the paintings, especially those made on the external walls, suggests that they may have been made by a Dutch painter, and perhaps in collaboration with some Iranian artists. In some of these scenes European men and women (the men presumably diplomats or merchants) are depicted.

The turbulent situation in Iran at the end of the Safavid era (1501-1736) brought to a halt the emergence of images of female figures on the walls of royal palaces and private homes. The Afghan invasion of 1722 and the capture of Isfahan turned the golden days of the Isfahanis into fear and desperation. These disastrous events encouraged the Ottomans to take advantage of the situation, and in 1723 they invaded from the west, ravaging western Persia as far as Hamadan, while the Russians seized territories around the Caspian Sea. This situation, however, did not last long, and with the emergence of a military genius from Khorasan by the name of Nader Quli Beg (1688-1747; later Nader Shah, r. 1736—1747), all invaders were expelled, and the country was unified again. Yet in the field of art relatively little effort was made (apart from some architecture and manuscripts), as Nader was at war throughout the period of his leadership.

But Nader Shah left behind a country with secure borders, which the next two dynasties were able to rule in peace. It was during these reigns of these two dynasties — the Zand dynasty (1750-1794), and the Qajar dynasty (1779-1925) - that art and artists again came to be praised, and figurative painting enjoyed further prosperity.

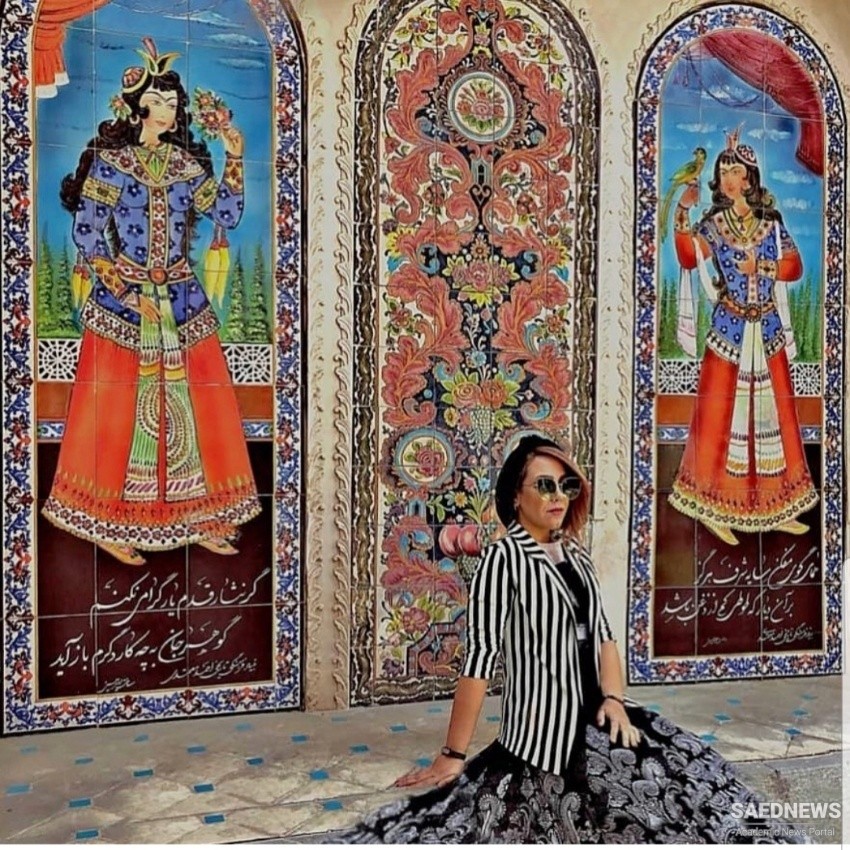

The output of this period constitutes a distinctive art style later known as the Qajar school — a style of painting developed in the royal courts of the Zand and Qajar kings. Qajar artists based their art on large-scale human figures. This iconography is found in many colorful media: tilework, embroidered felt tent-panels, and frescoes, as well as panel paintings. Although the execution and the techniques drew from Western oil-painting traditions, tter followed the same classic themes rincesses, lovers, and dancers. This trend about the mid 19th century, but with the lithography and photography (see below), il evolution suddenly opened up this royal :asure of the wider population.

European Paintings in Early Modern Persia

European Paintings in Early Modern Persia