Later, Iran would match up poorly against British and British Indian forces in terms of discipline, command of forces, logistics, and naval forces and coastal defense batt eries. Despite eff orts by various European military missions to pass along some of the tactical improvements and weapons developed during and aft er the Napoleonic wars, Qajar Iran lacked the resources and will to assimilate these new methods to achieve victory on the batt lefi eld against its major opponents. The Qajars generally prevailed only in confl ict with similar Ott oman, Afghan, and tribal forces.

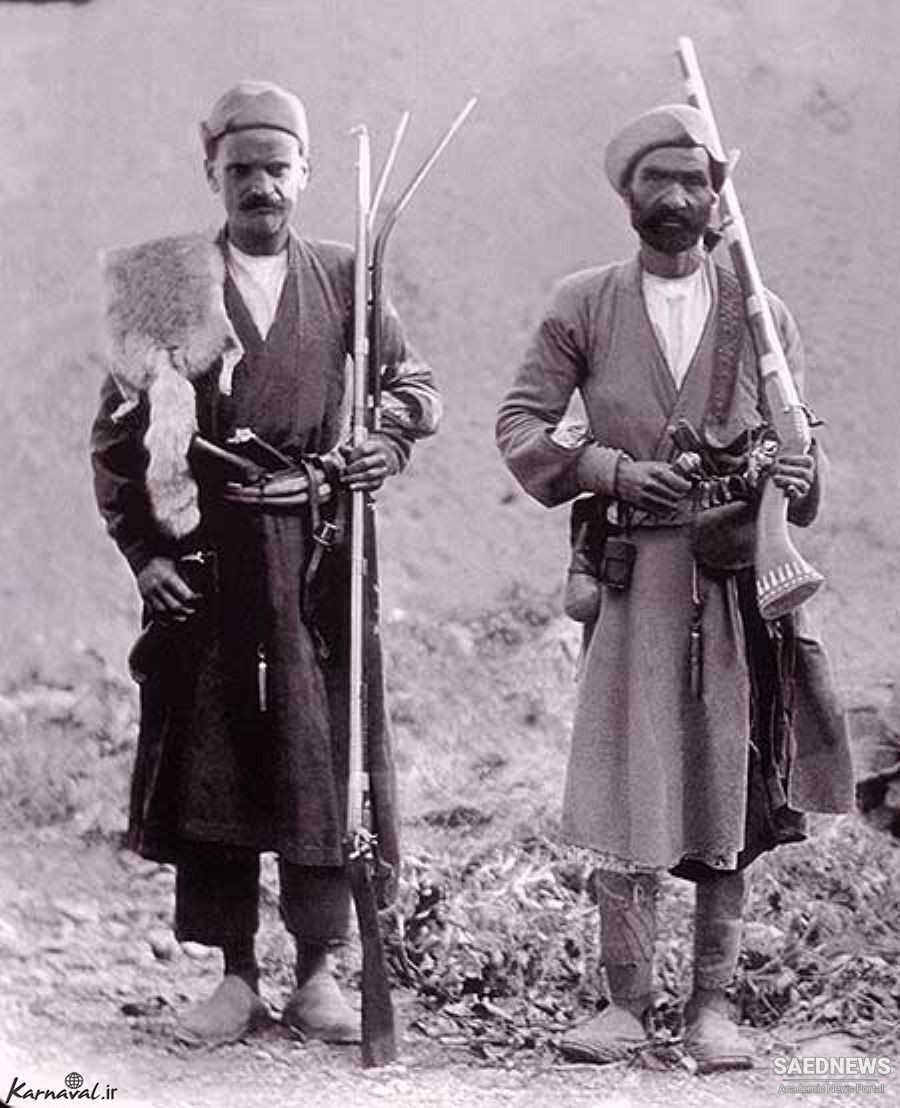

Standing Qajar military forces in the fi rst decade of the century consisted mainly of the royal guards and town garrisons. The royal guards, offi cered by Qajar nobles, contained four thousand ghulams armed with aging muskets. Most of Iran was ruled by tribes and landed nobles who provided levies of mounted fighters to the crown when called and, in return, got the right to collect tax revenues to cover their expenses and other needs. Litt le revenue made its way to the capital, and what did was usually wasted rather than invested in a standing military. In wartime, however, the regional levies could muster as many as eighty thousand generally well- prepared horsemen, who brought their own arms and kit. The tribal levies were expert horsemen and superior marksmen, capable of fi ring their muskets over their shoulders while galloping away from a foe. Many still used lance and bow, and all carried sabers of high- quality steel that they wielded with deadly skill. While these warriors could be assembled quickly, they might evaporate just as fast if their leader failed to hold them together. A British offi cial observed that they had “no further discipline than that of obeying their own leaders” and accepted as their leaders only “those of their own body they deemed their superiors.” Another British observer commented that the tribal contingents retained their separate identities even within the royal camp, noting that “since the army was mostly composed of men drawn from the diff erent tribes, each tribe was encamped in separate divisions." The Qajars had no functional heavy artillery at the turn of the nineteenth century and instead relied on the zanburak. The Iranians seem to have lost the camel- handling skills of Nader Shah’s army, however, and camels oft en ran amok, damaging Iranian formations as much as the enemy’s lines. Because the government provided so litt le to its fi ghters, the system worked well only when the Qajars were on the off ensive, the opportunities for plunder were plentiful, and the campaign could be completed quickly during nonwinter months.

The four Qajar shahs who ruled between 1797 and 1896 gave only slight, unsustained, and belated att ention to the creation of a modern military force that might protect them from external att ack and internal revolt. The fi rst major problem was the absence of any systematic att empt to integrate the tribes into Qajar political and military organizations as the Safavids had done. Instead, Qajar policies instituted under Crown Prince Abbas Mirza aft er 1805 were designed to weaken tribal power. The crown prince dismissed the tribal cavalry as a rabble, despite growing European adherence to Frederick the Great’s example of ending the intermingling of cavalry and infantry and returning the mounted forces to its original functions of shock action and scouting, the very roles in which Iranian horsemen excelled. One British official lamented that “to a nation devoid of organization in every other department of government a regular army was impossible . . . the tribes, the chivalry of the Empire, the forces with which [Nader Shah] overran the East, and which, ever yielding but ever present, surrounded, under Muhammad Khan, the Russian armies with a desert, were destroyed.” At the same time, Russian intrusions on Iranian territory in the early nineteenth century cut off Qajar access to Georgia. This made it diffi cult to replenish the ghulam corps that continued to serve as the shah’s personal guard and remained the central government’s most eff ective military force throughout the fi rst decades of the 1800s.

Qajars and the Military Crisis: Weak Army and Royal Ambitions

Qajars and the Military Crisis: Weak Army and Royal Ambitions