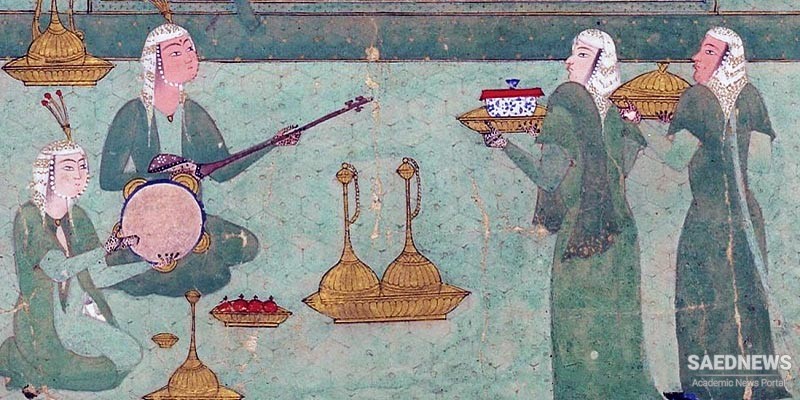

Of the musical arts of the earliest civilisations on the Iranian plateau, no tangible trace has remained. The Persian Empire of the Achaemenian dynasty (550-331 BC), with all its grandeur and glory, has left us nothing to reveal the nature of its musical culture. In the writings of the Greek historians, we find but a faint glimmer of the musical life of this period. Herodotus mentions the religious rituals of the Zoroastrians, which involved the chanting of sacred hymns. Xenophon, in his Cyropedia, speaks of the martial and ceremonial musics of the Persian Empire.1 The first document of any extent on Persian music comes to us from the Sassanian period (AD 226-642). At the Sassanian court, musicians had an exalted status. Emperor Chosroes II (Xosro Parviz), ruler from AD 590 to 628, the splendour of whose court is told in many legends, was patron to numerous musicians. Ramtin, Bamsad, Nakisa, Azad, Sarkas and Barbod were among the musicians of this period whose names have survived. Barbod was the most illustrious musician of the court of Chosroes II. Numerous stories about this musician and his remarkable skills as performer and composer have been told by later writers and poets. Barbod is credited with the organisation of a musical system containing seven modal structures, known as the Royal Modes (Xosrovdni); thirty derivative modes (Lahn); and three hundred and sixty melodies (Dastdri). The numbers correspond with the number of days in the week, month and year of the Sassanian calendar, but the implications are not clear (Source: The Dastgah Concept in Persian Music, Hormoz Farhat).

Older Millennia in Iranian Plateau: Unknown Cultures

Older Millennia in Iranian Plateau: Unknown Cultures