His grandfather was mostawfī (chief accountant) for the taxation of Fārs around 492/1099 under Atābak Rokn-al-Dawla or Najm-al-Dawla Ḵomārtegīn, who had been appointed governor there by Sultan Barkīāroq (487-98/1094-1105; Ebn Balḵī; pp. 3, 118). Ebn al-Balḵī apparently accompanied his grandfather in his journeyings through the province, thus acquiring a first-hand knowledge of local conditions, topography, crops, etc. He was subsequently commissioned by Barkīāroq’s successor Ḡīāṯ-al-Dīn Moḥammad (d. 511/1118) to put together an account of Fārs (Ebn al-Balḵī, pp. 2-3, 118). This Fārs-nāma is accordingly dedicated to the Saljuq sultan; and since it frequently mentions as still living Atābak Faḵr-al-Dīn Čāvlī Saqāʾū (d. 510/1116; cf. Camb. Hist. Iran V, pp. 116-18), it must have been composed before that date.

Some two-thirds of the Fārs-nāma is devoted to the pre-Islamic rulers of Persia and the Arab conquest of Fārs. Although there is some material here in common with such earlier Arabic sources as Ṭabarī and Ḥamza Eṣfahānī, there is much additional information on pre-Islamic Persia, making the work a valuable primary source (Camb. Hist. Iran III/2, p. 1279). Ebn al-Balḵī frequently projects back material pertaining to the Sasanian period into the mythical past of Persian national mythology; he says that the city of Eṣṭaḵr was built by Gayōmarṯ and attributes Sasanian administrative procedures and court ceremonies to Goštāsp (“Veštāsf”; pp. 26-27, 48-49; cf. Camb. Hist. Iran, III/1 pp. 363, 402-03). Interesting material is given on Mazdak and his movement (pp. 86-91).

The last third of the Fārs-nāma (pp. 119-72) includes a geographical account of the province, district (kūra) by district, with notes on its antiquities and fortresses and many historical details. For example, he describes events in Shiraz when it was the capital of the Buyid ʿAżod-al-Dawla and the raids and depredations during the fighting between the Saljuq amir of Kermān, Qāvūrd b. Čaḡrī Beg, and the Šabānkāra chief Fażlūya (pp. 132-4), and he notes the decline of the once flourishing Persian Gulf port of Sīrāf, despite the efforts of the Atābak Ḵomārtegīn (pp. 136-37). This topographical section is followed by a section on the ethnography of Fārs containing valuable material, especially on the early Islamic history of the Kurdish Šabānkāra and their renowned chief, Fażlūya (5th/11th century), and also on the other Kurdish tribes of Fārs, the five so-called romūm (sing. ramm) or clans (pp. 164-69). The work closes with an account of the revenue assessment (qānūn-e māl) of Fārs and some remarks on the province’s history under the last Buyids (pp. 170-72).

Two centuries later, Ebn al-Balḵī’s section on topography of Fārs was much used by Ḥamd-Allāh Mostawfī for his Nozhat al-qolūb. Finally, in the 19th century, Ḥājī Mīrzā Ḥasan Fasāʾī echoed the title of Ebn al-Balḵī’s work in his own Fārs-nāma-ye nāṣerī.

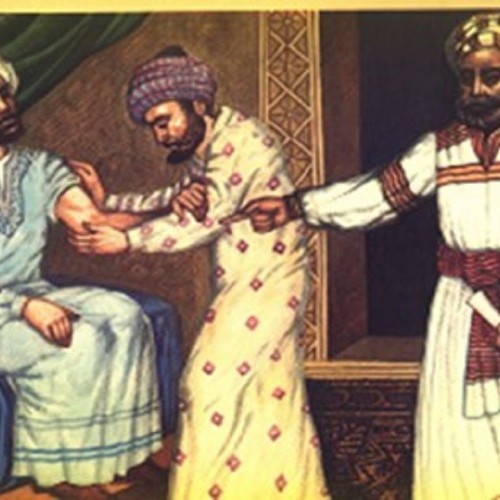

Muqim Arzani the Physician

Muqim Arzani the Physician