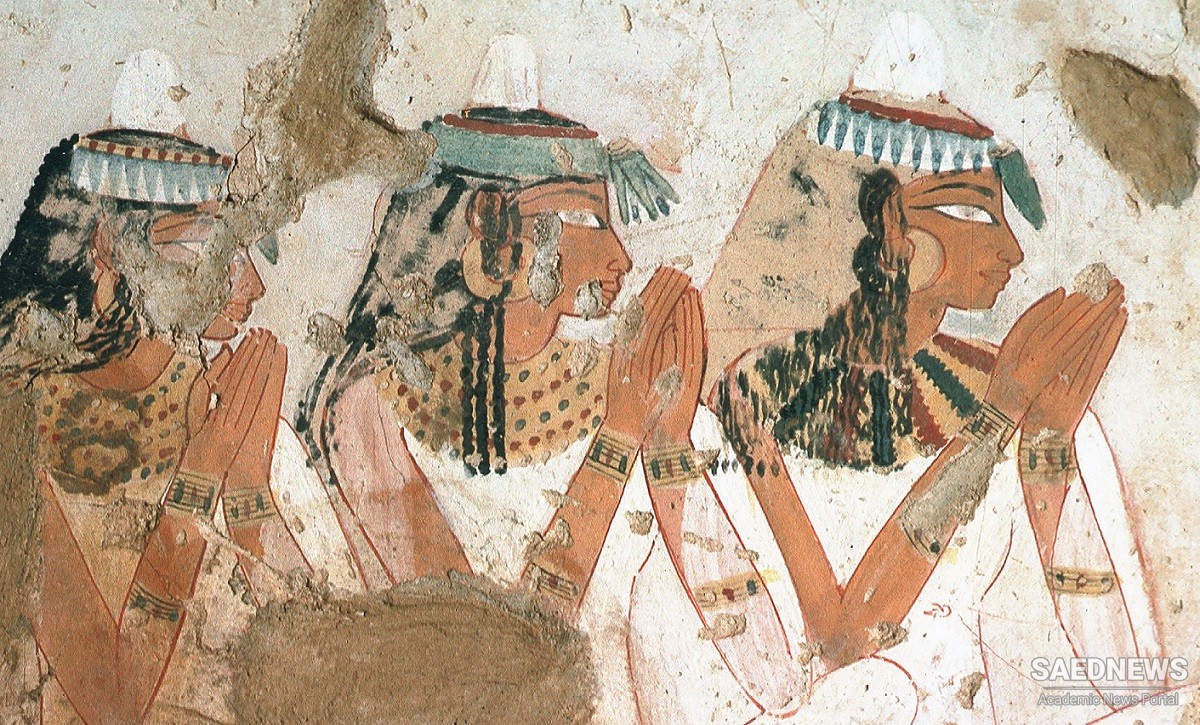

The Egyptian flute was a so-called vertical flute (not a transverse flute); the player held it slanting obliquely downwards and blew across the open upper end against the opposite, sharp edge. It shared the name ma .t or m .t with both clarinets and oboes, the ending t indicating the feminine gender. Any other names given by previous writers to th e Egyptian flute are erroneous.

Egyptian flutes are smaller than many primitive ceremonial flutes. Cut from a simple cane generally a yard long and half an inch wide, the Egyptian flute had from two to six fingerholes near the lower end; one excavated specimen was even provided with a thumb hole in the back. This simple cane flute without a whistle head might be supposed to be older than whistle flutes, but it is not.

Its comparatively small size enables the player to blow it without the aid of a mouthpiece. In primitive civilizations we find much larger flutes, whose size necessitates the use of a whistle head because the breath of the player is too weak to blow across so wide an opening. Vertical flutes, such as the Egyptian flutes, had greater musical possibilities than the whistle flutes.

Being able to vary the angle of blowing against the edge, the player could give more expression to the tone; no instrument had a more incorporeal sound, a sweeter sostenuto, a more heartfelt vibrato. The flute, with its characteristic quality, still exists today all over the Islamic world. It is best known under its Persian name n y, which has replaced the arabic name qa.

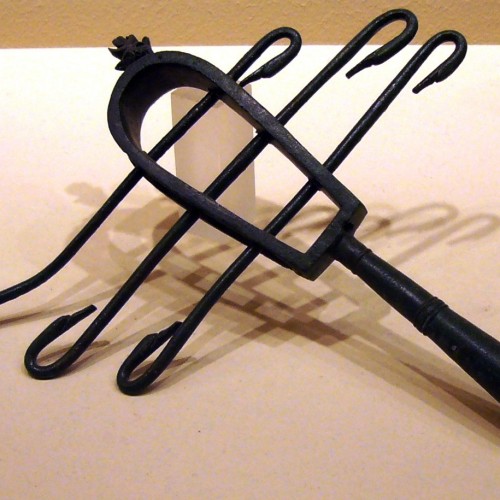

Egyptian Musical Instruments: Sistrum

Egyptian Musical Instruments: Sistrum