Ernest Orlando Lawrence was born on August 8, 1901, in Canton, South Dakota. In 1919, he enrolled at the University of South Dakota, receiving his undergraduate degree in chemistry in 1922. The following year, he received his master’s degree from the University of Minnesota. He then spent a year in physics research at the University of Chicago. Under scholarship to Yale University, Lawrence completed his Ph.D. in physics in 1925. Following graduation, he remained at Yale for another three years, first as a postdoctoral fellow and then as an assistant professor of physics.

In 1928, Lawrence accepted an appointment as associate professor of physics at the University of California in Berkeley. This academic appointment began a lifelong relationship for Lawrence with the university, and the association allowed him to bring about great changes in the world of nuclear physics. Two years after his initial academic appointment, he advanced to the rank of professor, becoming the youngest full professor on the Berkeley campus. In 1936, he also became director of the university’s Radiation Laboratory. He retained both positions until his death.

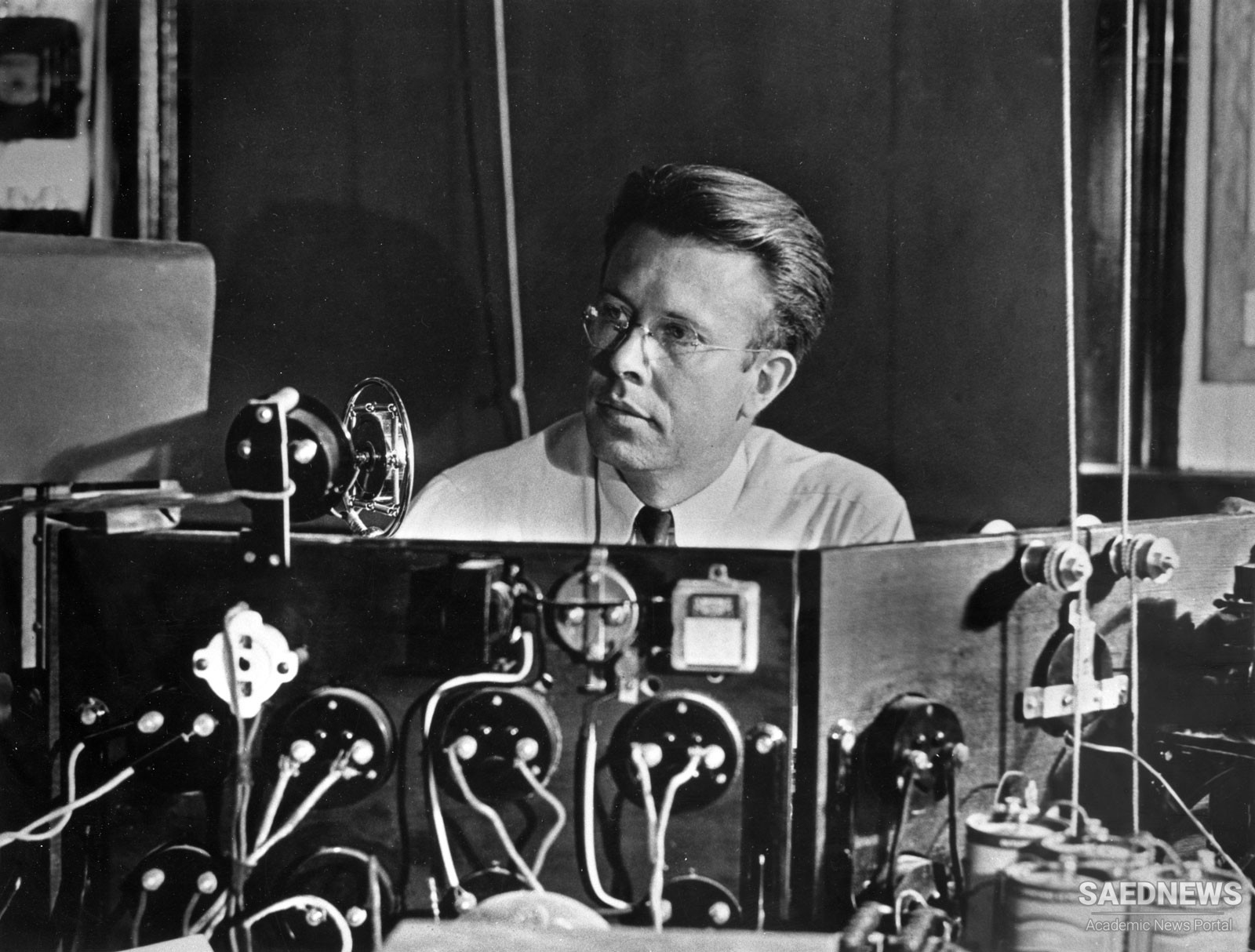

Lawrence’s early nuclear physics research involved ionization phenomena and the accurate measurement of the ionization potentials of metal vapors. In 1929, he made a major contribution to nuclear technology when he invented the cyclotron—an important research device that uses magnetic fields to accelerate charged particles to very high velocities without the need for very high voltage supplies. Developed and improved in collaboration with other researchers, Lawrence’s cyclotron became the main research tool at the Radiation Laboratory and helped to revolutionize nuclear physics for the next two decades. As more powerful cyclotrons appeared, scientists from around the world came to work at Lawrence’s laboratory, where they organized into highly productive research teams. Not only did Lawrence’s cyclotron provide a unique opportunity to explore the atomic nucleus with high-energy particles, but his laboratory’s scientific team kept producing high-impact results that were beyond the capabilities of any one individual working alone.

Lawrence received the 1939 Nobel Prize in physics for “the invention of the cyclotron and the important results obtained with it.” Because of the hazards of wartime travel, Lawrence could not go to Stockholm for the presentation ceremony. Just prior to direct U.S. involvement in World War II, Edwin McMillan (1907–1991) and Glenn Seaborg (1912–1999) discovered the first two transuranic elements, neptunium (Np) and plutonium (Pu) at the Radiation Laboratory. The discovery there of plutonium and its superior characteristics as a fissile material played a major role in the development of the U.S. atomic bomb. Lawrence’s Radiation Laboratory became a secure defense plant during World War II, and its staff members made many contributions to the overall success of the Manhattan Project.

Lawrence himself was given responsibility for uranium enrichment work—a challenging and stressful task that taxed his health. To support the giant uranium-235 enrichment effort emerging in Oak Ridge, Tennessee, Lawrence designed a device called the calutron. It was a clever, but technically pesky, electromagnetic isotope separation device, consisting of a 94-cm (37-inch) cyclotron and a 467-cm (184-inch) magnet leading into the mass spectrographs. Almost all of the highly enriched uranium-235 in Little Boy, the atomic weapon that destroyed Hiroshima, passed through Lawrence’s calutrons in Oak Ridge.

Baron Ernest Rutherford (1871-1937)

Baron Ernest Rutherford (1871-1937)