Charles Seeger was an original and sometimes thorny thinker whose writing and activism encompassed musicology, ethnomusicology, composition, and music theory. He worked on folk music collecting, administration, and publishing in a number of federal agencies from 1936 to 1953. His second wife, Ruth Crawford Seeger, a noted modernist composer, contributed folk-song studies. Of Charles’s children, Pete has had the greatest public infl uence as singer, songwriter, and activist. A key figure in the “folk revival” that stretched from the 1940s to the early 1960s, he was a member of the Almanac Singers and the Weavers.

Pete Seeger suffered anticommunist blacklisting in the 1950s and beyond, but eventually became a much-honored living legend and a mentor of Bruce Springsteen. Mike Seeger played a pivotal role in promoting little-known American folk musicians and as part of the New Lost City Ramblers; Bob Dylan has called him “the supreme archetype” of a folk musician. Peggy Seeger has carried on similarly infl uential work after moving to Great Britain, originally teaming up with her husband, Ewan MacColl, to spur the folk revival there.

With a broader sense of national identity and the success of the recording industry, African American music came to be appreciated as a source of, and eventually as an infl uence on, mainstream American music. Yet the focus on British Isles origins—and later on black music—meant that it took until late in the twentieth century for Latino, Jewish, and many other ethnic groups to be recognized for their roots folk music. Striking miners in Appalachia in the twentieth century might have been listening to a Hungarian band as well as an English tune, but that possibility does not fi gure in the national imaginary about the coalfi elds. Other regional styles were overlooked. Writing about the upper Midwest group The Goose Island Ramblers, all of northern and central European heritage, Jim Leary says that “the neglect of upper Midwesterners generally requires nothing less than a reassessment of what constitutes American folk music.”

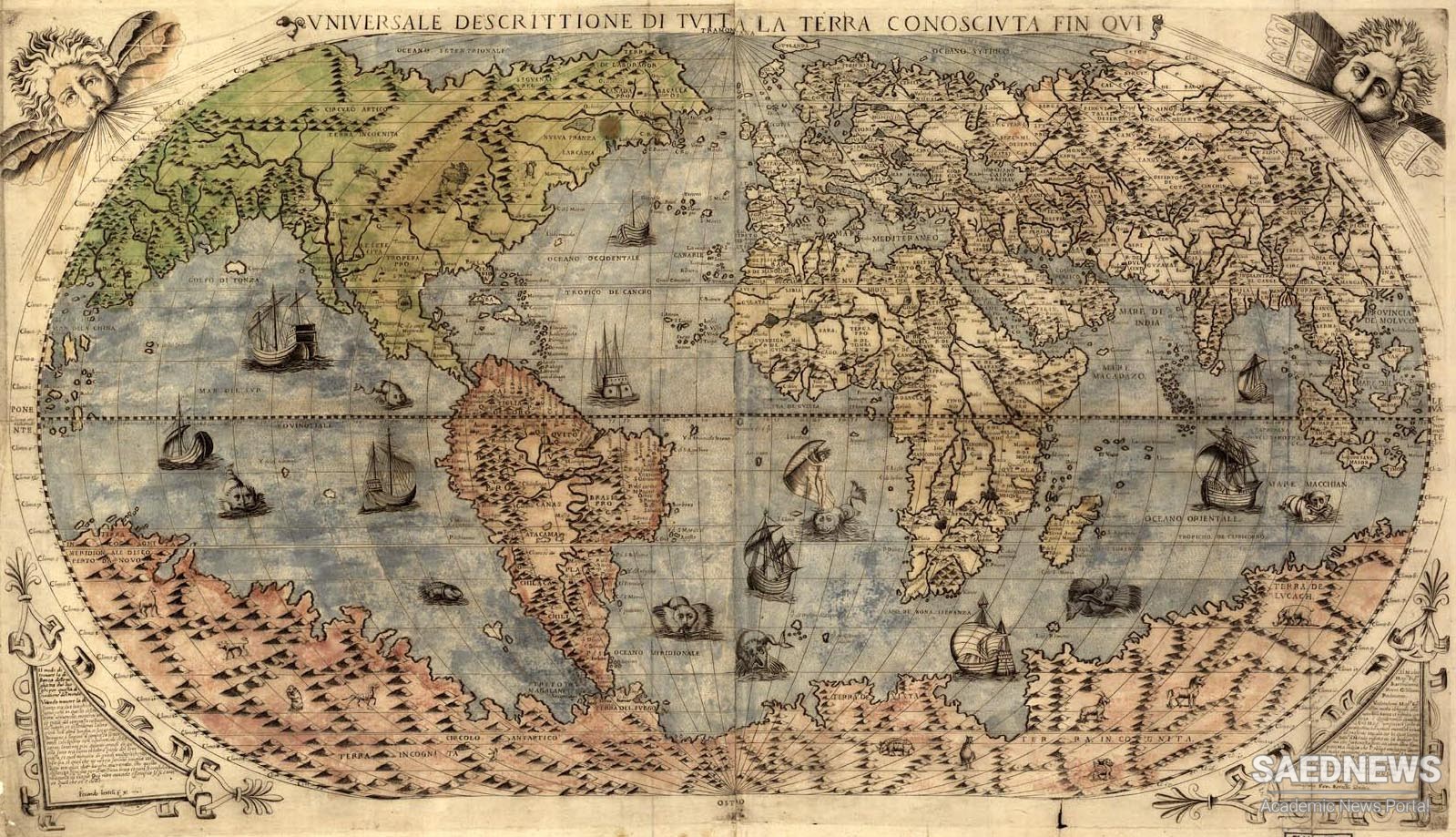

In other regions around the world, the story played out under conditions set by Europeans. For hundreds of years, travelers, missionaries, and colonialists heard folk music around the world. They often disdained local folk songs but paid tribute to what they thought of as ancient, “civilized” high-culture music, concentrating on the courtly traditions of the kingdoms of the Middle East, India, and China. Jaap Kunst, a Dutch scholar-administrator living in Indonesia, who coined the word “ethnomusicology” around 1950, made a specifi c instrument-set, the gleaming bronze gamelan of the Javanese sultans, famous, rather than the songs of villagers. He was responding to the standard three-part model of the world’s musics: oriental to describe the ancient-civilization approach, primitive for all the indigenous musics of Africa, Oceania, and the Americas, and folk for the “internal primitives” of Europe: the peasants and farmers.

Globally, this set of divisions of the world of music spread, as local intelligentsia members adopted or adapted the Euro-American idea of intellectual intervention. In Latin America and the Caribbean, the Europeanized upper class downplayed the traditions of indigenous peoples and the imported African workforce in favor of a search for “Hispanic” styles as the basis for national music cultures. In the “oriental” zone, local elites also neglected folk music in favor of what the West had defi ned as being of value: court and urban professional styles and histories. In parts of Africa, the infl uence of missionaries downgraded or suppressed village musics, as also happened in Oceania. As these regions emerged from the long cultural shadow of European domination, they began to rethink vernacular music. Martin Stokes says, for example, that “folk music is presented by many musicians and folklorists in Turkey as a timeless and self-evident fact of Turkish cultural life,” and “is considered by its proponents and practitioners to play a specifi c role in creating a culturally unified and cohesive nation-state.”

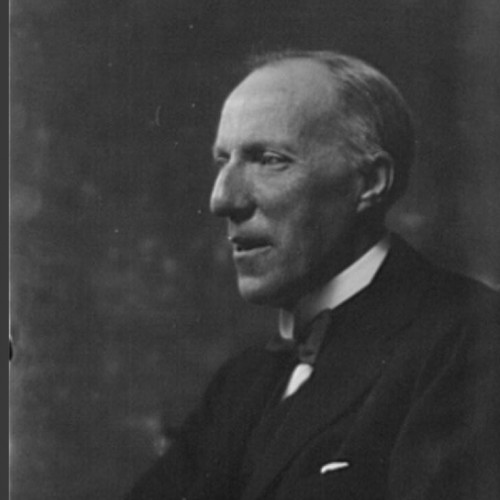

Cecil Sharp and English Volk Music

Cecil Sharp and English Volk Music