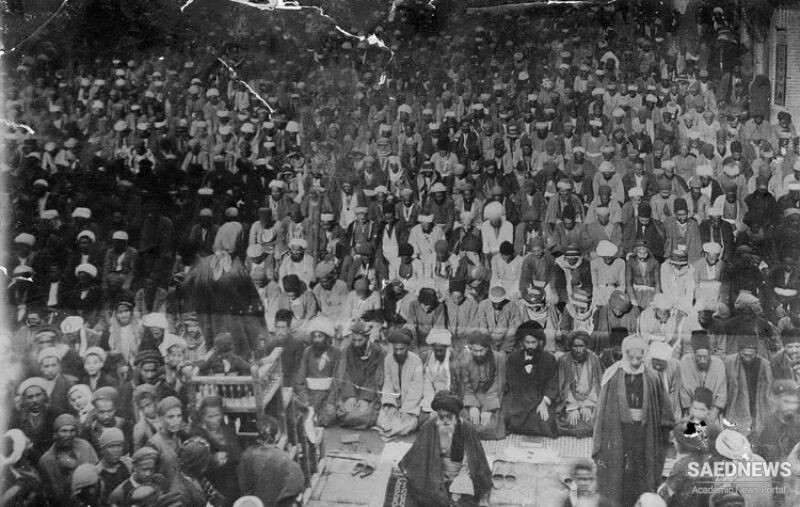

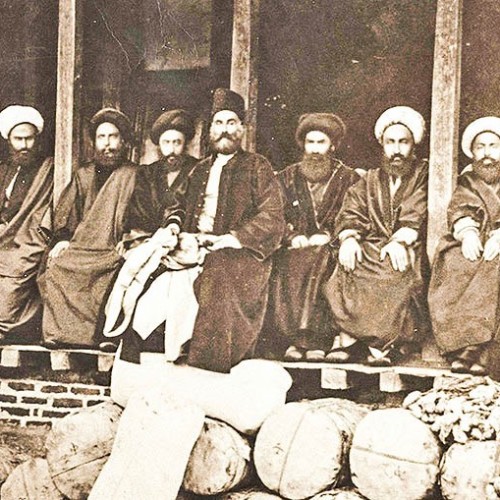

Whether it was Afghani’s provocation or the emerging consensus among dissidents and discontent merchants, the Tobacco Protest had widened the gap between the state and the ulama, and displayed the latter’s compliance with the grievances of their mercantile clients. Popular involvement was an unexpected outcome of a protest rooted in deeper economic problems. In Iran men and women complied with Shirazi’s fatwa in public and in private. Water pipes were broken and thrown into the streets, or otherwise stored in backrooms and out of sight. Tobacco retailers shut their businesses, and banners were brought out to demonstrate public solidarity. To the shah’s great annoyance, apparently even women of his own harem refrained from smoking on the grounds that they followed the marja‘-e taqlid on religious issues, not the shah. The public ban, perhaps aggravated by tobacco withdrawal symptoms, demonstrated the power of mass protest and persuaded people to take even bolder steps. Negotiations with Amin alSoltan, exchanges of telegrams between the shah and the ulama, and between the mojtaheds in the capital and in the provincial centers, added to the sense of urgency. The rebellion was no longer localized or confined to one economic sector but increasingly gave voice to popular frustrations on a national scale.The prerevolutionary scene—complete with vigilante enforcement of the smoking ban, appearance of clandestine posters and leaflets known as “night-letters,” and declaring a curfew in the capital—reached its climax in January 1892. The government’s threat to expel from the capital the chief mojtahed of Tehran, Mirza Hasan Ashtiyani, if he continued to provoke the public and refrain from breaking the smoking ban, backfired. He refused to accept the terms offered by the government. The violent demonstration soon after, following the closure of the bazaar, brought a huge crowd to the Arg square in front of the royal citadel calling not only for the repeal of the tobacco monopoly but also for an end to government corruption and the shah’s despotic rule. The crowd showered insults not only on Kamran Mirza, who served as governor of the capital and minister of war, but also on the premier Amin al-Soltan and on the person of the shah. This was followed by an attempt to break through the gates of the citadel. The armed confrontation with the royal guards and the elite troops who were brought in to defend the royal compound, ended in the deaths of ten demonstrators, with many more injured (Source: Iran a Modern History, Abbas Amanat).

Royal Gift for Major G. F. Talbot: The Regie Monopoly

Royal Gift for Major G. F. Talbot: The Regie Monopoly