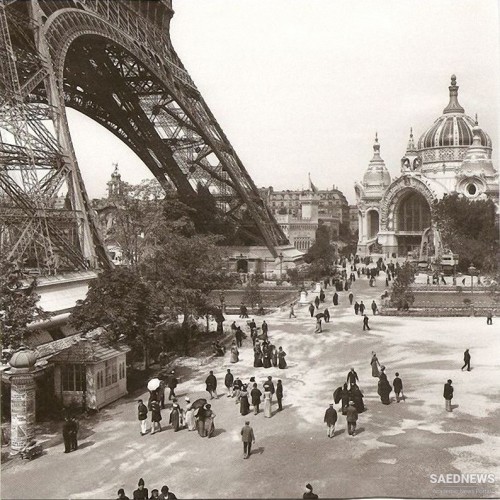

The French Republic was identified in the minds of its supporters as the bastion of the enlightenment and so, curiously, despite their frozen attitude towards the desirability of social change, republicans saw themselves as the people who believed in progress and the modern age. This was only possible because they could identify an ‘enemy to progress’ in the Church and its teachings. More passion was expended on the question of the proper role of the Church and the state during the first three decades of the Third Republic than on social questions. In every village the secular schoolteacher represented the Republic and led the ranks of the enlightened; the priest led the faithful and the Church demanded liberty to care for the spiritual welfare of Catholics not only in worship but also in education. Republicans decried the influence of the Church as obscurantist and resisted especially its attempts to capture the minds of the rising generation of young French people. The Church was supported by the monarchists, most of the old aristocracy and the wealthier sections of society; but ‘class’ division was by no means so complete and simple as this suggests: the Church supporters were not just the rich and powerful. The peasantry was divided: in the west and Lorraine, they were conservative and supported the Church; elsewhere anti-clericalism was widespread. In the towns, the less well-off middle classes and lower officials were generally fervid in their anti-clericalism. Their demand for a ‘separation’ of state and Church meant in practice that the Church should lose certain rights, most importantly, its right to separate schools. The Catholic Church in France by supporting the losing monarchial cause was responsible in good part for its own difficulties. In the 1890s the Vatican wisely decided on a change and counselled French Catholics to ‘rally’ to the Republic and to accept it; but the ralliement was rejected by most of the French Catholic bishops and the Church’s monarchist supporters. The Dreyfus affair polarised the conflict with the Church, the monarchists and the army on one side and the republicans on the other. Whether one individual Jewish captain was actually guilty or not of the espionage of which he stood accused seemed to matter little when the honour of the army or Republic was at stake.

France at the Turn of Century: Divided and Impotent

France at the Turn of Century: Divided and Impotent