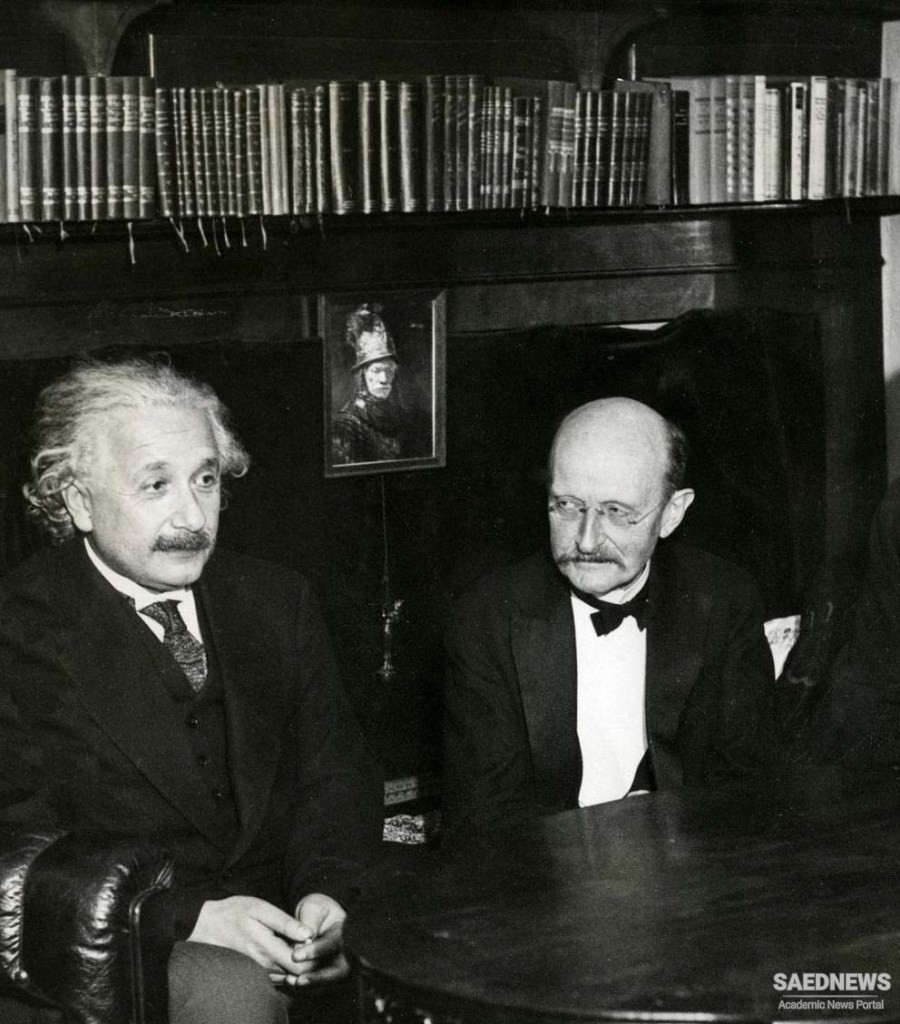

Stimulated by Dalton’s atomic hypothesis, other chemists busied themselves identifying new elements and compounds. For example, by 1819, the Swedish chemist Jons Jacob Berzelius (1779–1848) had increased the number of known chemical elements to 50. That year he also proposed the modern symbols for chemical elements and compounds based on abbreviations of the Latin names of the elements. He used the symbol O for oxygen (oxygenium), the symbol Cu for copper (cuprum), the symbol Au for gold (aurum), and so forth. Over his lifetime, this brilliant chemist was able to estimate the atomic weights of more than 45 elements—several of which he personally discovered, including thorium (Th) (identified in 1828). While nineteenth-century chemists filled in the periodic table, other scientists, like the British physicists Michael Faraday (1791–1867) and James Clerk Maxwell (1831–1879), were exploring the nature of light in terms of electromagnetic wave theory. Their pioneering work prepared the way for the German physicist Max Planck (1858–1947) to introduce his quantum theory in 1900 and for the German-Swiss-American physicist Albert Einstein (1879–1955) to introduce his theory of special relativity in 1905. Planck and Einstein provided the two great pillars of modern physics: quantum theory and relativity. Their great intellectual accomplishments formed the foundation upon which other scientists in the twentieth century formulated a more comprehensive theory of the atom, explored the intriguing realm of the atomic nucleus and its amazing world of subatomic particles and energetic processes, exploited the equivalence of energy and matter through nuclear fission and fusion, and discovered the particle-wave duality of matter.

From Nuclear Fission to Nuclear Disaster

From Nuclear Fission to Nuclear Disaster