The multiplicity of notes in ancient Greek music must certainly have made it a very long and laborious study, even at a time when the art itself was in reality very simple. Hence it is not surprising to find that Plato, though he was unwilling that youth should bestow too much time upon music, allowed them to sacrifice three years to it, merely in learning the elements ; and thought that he had reduced this study to its shortest period: but at the end of this time, a student could hardly be capable of naming all the notes, and of singing an air at sight, as we call it, in all keys and in all the genera, accompanying himself at the same time upon the lyre ; much less could it be expected that he should be correct in every species of rhythm ; that he should be master of taste and expression; or be able to compose a melody himself to a new lyric poem. It was much more difficult to sing from the tablature, than to follow a voice or instrument, as it is far more perplexing to read the Chinese language than to speak it, on account of the great multiplicity of characters. However, if we could find Greek music now, we should be able to read it, contrary to the general opinion, which is, that the ancient notation is utterly lost. But though we can perhaps decypher it as exactly as the Greeks themselves could have done, yet to divide it into phrases, to accentuate, and to give it the original and true expression, are things, at present, impossible, and ever will remain so. For it is with the music of every country as with the language ; to read it with the eye, and to give it utterance, are different things ; and we can arrive at no greater certainty about the expression of a dead music, than the pronunciation of a dead language.

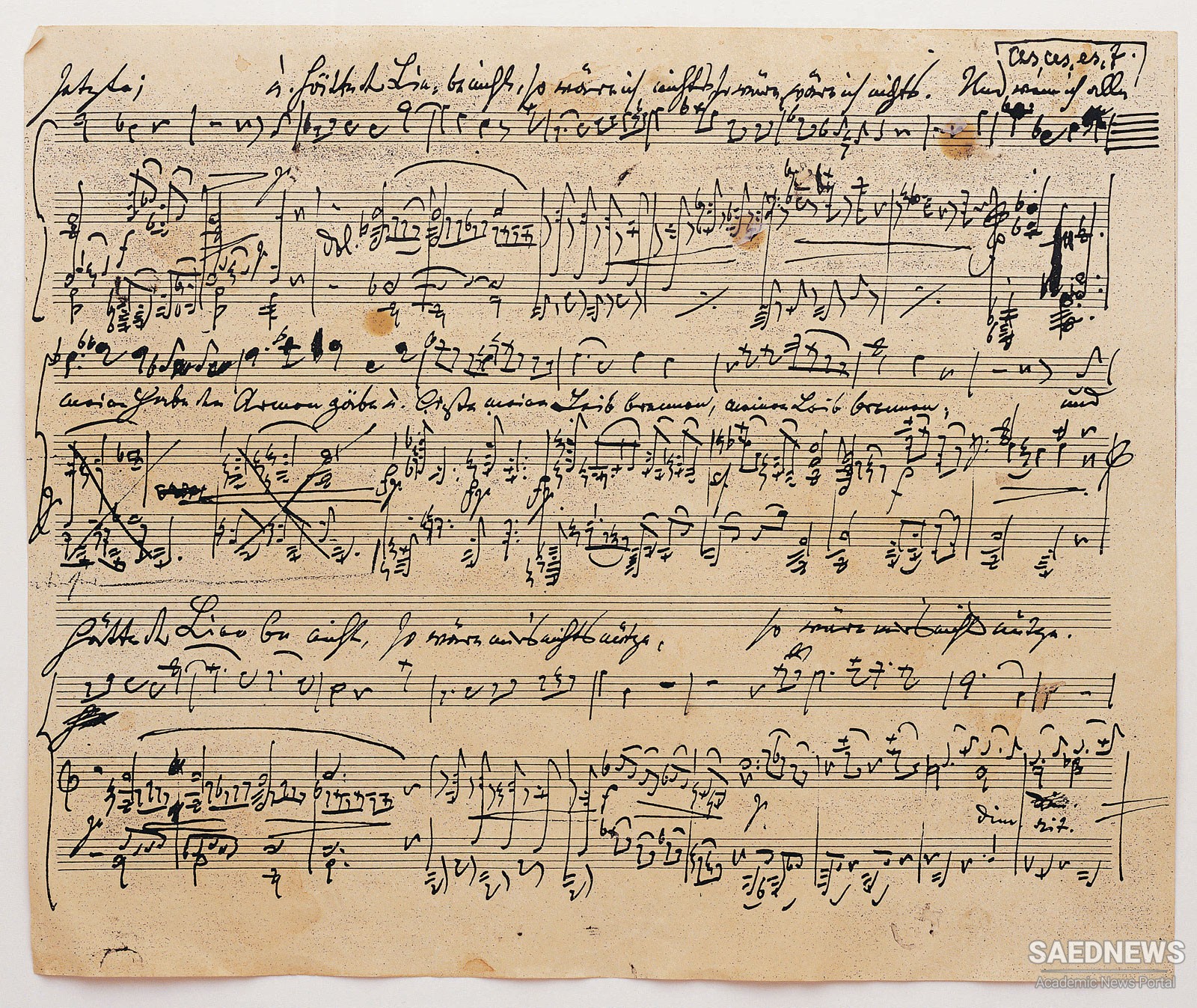

Five Tetrachords of General System of Greek Music

Five Tetrachords of General System of Greek Music