More than many other scholars Schaeder was a self-made man, educated in a strictly European way. His personal connection with countries outside Europe was almost nil. He never visited the East and did not take much scholarly interest in contemporary problems of the Near, Middle, or Far East (Pritsak, p. 25). For Schaeder, as he himself admitted, the “Orient” was not the idealized world of romanticism and immeasurable wisdom but the alternative plan to the unique occidental culture. Occidental culture won its freedom, according to Schaeder, from its characteristic, never resolved tension between “Christian revelation” and “Greek education” (Goethe als Mitmensch, pp. 5-6). This freedom was never and nowhere achieved in the “Orient” with its monocausal forms of culture. It is all the more astonishing to see how much ingenuity and time Schaeder devoted to his research into eastern and mainly Iranian cultures.

Schaeder is described by those who knew him personally as an independent, passionate scholar. His thirst for knowledge was inexhaustible. It was not unusual for one idea to project or to chase the other, but this gift of overwhelming inspiration had its price. Many of the envisaged plans remained torsos or even unwritten at all. Neither Schaeder’s doctoral dissertation nor his habilitation thesis have ever been properly published (Pritsak, p. 24).

Schaeder often took the short cut of giving public lectures on whatever topic he was currently interested in or asked to talk about. He was an impressive orator who could be sure that his words would fill the lecture halls.

It was not easy to become Schaeder's pupil. Schaeder was permanently looking for gifted students who more or less fulfilled the preconditions of academic work. If they somehow disappointed the master, those “Genies vom Dienste” (geniuses at the service) could find themselves replaced by others. Yet some of his best students did not give in and became well-known scholars in their own right. Suffice it to mention the renowned Islamicist Annemarie Schimmel (1922-2003) and the noted historian of oriental religions, Carsten Colpe (1929-2009). The last student to study with Schaeder was Hans Helmhart Kanus-Credé, a scholar of the Šāh-nāma.

Schaeder's life and professional career was very much determined by his father, professor Erich Schaeder (1861-1936) who taught Protestant theology at several universities. The educational level in his parental home as well as the classical schools he was privileged to attend prepared him in the best possible way and in many respects for his further private and academic life. Thus Schaeder came to be a gifted pianist, even introduced into the art of writing music (Pritsak, pp. 21-22).

Schaeder’s first classical studies in 1914 at the university of Kiel were interrupted by the outbreak of the First World War. Schaeder did voluntary service as a medical orderly in Russia and Rumania (where he came closest to the real “Orient”). He continued his classical studies after the end of the war with Werner Jäger (1888-1961). It was the historian Fritz Kern (1884-1950) who drew his attention to the East. He needed a gifted person who was able to read medieval Arabic sources on German countries in their original language. Not only did Schaeder fulfill Kern's expectations, he even chose the Middle East and above all Iran as the worthwhile subject of his further studies.

Schaeder took all his academic degrees in an incredibly short time. He was awarded his doctorate in 1919 with a thesis on the early Islamic theologian Ḥasan Baṣri, and he took the habilitation degree in 1922 with a study on the poetical means and motives of Šams-al-Din Moḥammad Hafez (Hafizstudien). Omeljan Pritsak (1919-2006), who must have seen this unfortunately unpublished work, says that it was (or is?) an introduction to the arts of classical Persian poetry (Pritsak, pp. 28-29).

During his studies Schaeder worked in Berlin as a cultural journalist for publications such as the conservative Grenzbote and became active in ephemeral Christian oriented conservative circles in 1920 and 1921 (Pritsak, pp. 25-26).

Schaeder was not introduced into Iranian studies by, and at the time dominate and rival, schools of F. C. Andreas and Chr. Bartholomae. Schaeder was and remained independent of both schools all his life. Instead he owed his introduction into his later working field to such contrasting scholars as the German orientalist and politician in Prussia C. H. Becker (1876-1933), and the secluded polymath J. Markwart. It is obvious that both of them influenced the subject of his work and even the form and arrangement of his articles.

In 1922, the year of his habilitation, Schaeder was appointed to his first professorship at Breslau where he stayed till 1926. This time is regarded as the most productive period of his life. Pritsak stated that Schaeder, in steady contact with outstanding specialists and through studies of his own, acquired an amazing knowledge of Semitic, Iranian and Turkic languages, of philosophy, religious science and general linguistics, and such important works as “Urform und Fortbildungen des manichäischen Systems” (1927) and Die Komposition von Esra 2-4 (often called Esra der Schreiber) were written at that time (1930; Pritsak, pp. 29-31).

Schaeder became professor at Königsberg (and for a brief period at Leipzig) from 1926 to 1931. In 1930, Markwart died and Schaeder was appointed as the successor to his chair, unique in Germany, for Iranian and Armenian philology. He occupied the chair from 1931 to 1944 (Pritsak, p. 29). This was the time of the Third Reich, and without doubt the most problematic period of Schaeder’s life. Schaeder shared with the new regime a basic national bias, but what he wrote during that period does not compel us to suspect that his scholarly work had undergone any influence from the side of fascist primitive racism and expansionism. Moreover, Schaeder always wrote in a respectful way about the merits of his Jewish colleagues. But Schaeder did not leave Germany, and a kind of inner emigration would have been impossible for a man of his moods. On the contrary, from 1933 to 1935 he stepped forth as the director of the Orientalisches Seminar of the University of Berlin (Pritsak, p. 34).

One must also say that Schaeder allowed himself to be misused by the Nazi propaganda as the kind of scholar they liked to show off. The impression Schaeder made abroad is best characterized by an episode in C. P. Snow's novel The Light and the Dark (1947, pp. 214-25). The hero of Snow’s story, Roy Calvert (alias Charles R. C. Allberry), had and kept close contacts with German colleagues and repeatedly visited Germany even under fascist rule. During his visit to Germany in 1938 he met and was received by a high-ranking official whose name was—with a slight spelling deviation—(Reinhold) Schäder.

Schaeder left Berlin in 1944 and went back to Göttingen. There he soon obtained the well-designed chair of Orientalische Philologie und Religionsgeschichte that he kept till 1957, the year of his death. The last years of his life are described as an unhappy sequence of depressions and diseases (Pritsak, p. 21). It was certainly also a time of scholarly decline. The religious and the aesthetic components in Schaeder’s life may have given him some last comfort, as his conversion to the Catholic faith seems to testify.

Schaeder and Iranian Studies. Of about 260 publications (monographs, articles, obituaries, reviews, translations into German, editions, printed lectures, journalistic essays) circa 90 are mainly devoted to Iranian and Manichaean studies. The figure is sufficient to show that these two subjects are the main part of Schaeder’s scholarly oeuvre.

It was not Schaeder's aim to distinguish himself as a first editor of those texts or art objects that had become accessible in the first half of the 20th century and that revolutionized Iranian studies. His editions of Iranian Turfan texts are insignificant. He was the ideal scholar to work up the results of the editorial work of others, to point out in which way and to which degree they corrected or completed our current knowledge, and, if possible or necessary, to improve on the editions themselves.

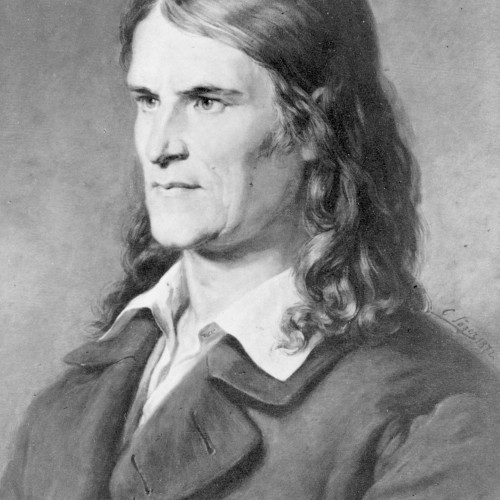

Friedrich Rückert

Friedrich Rückert