Whether the date is 270 or 273, Hormizd, or Hormizd-Ardashir as he is known from inscriptions, ruled only a little more than a year before he died. Nothing is known of his short reign except a notice in the Arabic history of al-Tha'alibi that he waged war against the Sogdians, not improbable in view of his reputation for valour in war.

With the accession of Varahran I, or, to use the later form of the name, Bahram, we may sense a change in the dynasty. Bahram was not the son of Hormizd, as some later Arabic and Persian writers supposed; rather he was another son of Shapur, and he was called the king of Gilan, in the great inscription of Shapur I. In this inscription, Bahram was not honoured by a fire in his name, as were both Hormizd and Narseh. This may indicate that Bahram's mother was a lesser queen or possibly even a concubine. Narseh, king of the Sakas and of the east, most probably objected to the accession of Bahram II, son of Bahram I, but he certainly blamed the father, since in one instance he substituted his own name for that of Bahram I on a rock-inscription of Bishapur.

We may believe that the problem of succession to the throne had not been settled in a manner agreeable to all princes, and Narseh may have thought he should have succeeded his brothers, but we have no evidence that he revolted. When Bahram I arranged for his son Bahram II to succeed him, Narseh was surely unhappy but bided his time. Bahram I ruled only three years and during his reign, Aurelian brought an end to Palmyra and re-established Roman rule in the east. Under Bahram I the priest Kartlr, or Kerdir, continued his career of consolidating the state church, and incidentally of self-aggrandizement. He was probably the main influence in the imprisonment and death of Man! which took place under Bahram I.

The religious history of the reigns of Hormizd and the two Bahrams is dominated by the figure of Kartlr, who may have been the real power behind the throne of Bahram II. One might speculate that the priest used his influence in securing the succession to the throne for Bahram II, rather than for Narseh. The latter seems to have followed a liberal policy towards religious minorities in the empire, much like his father, Shapur, whereas the Bahrams were more amenable to the wishes of the conservative Zoroastrian priesthood. Apart from his religious impact, Kartir's influence on political affairs should not be underestimated.

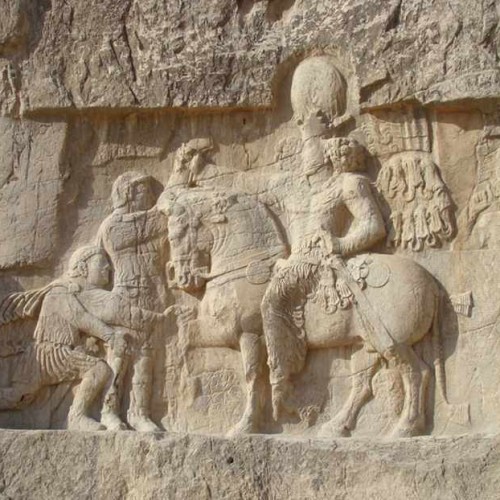

War of Shapur and Valerian

War of Shapur and Valerian