Yet the Upper Palaeolithic world was still a rather empty place. Calculations suggest that 20,000 humans lived in France in Neanderthal times; this becomes possibly 50,000 out of perhaps 10 million humans in the whole world twenty millennia ago. ‘A human desert swarming with game’ is one scholar’s description of it. They lived by hunting and gathering, and a lot of land was needed to support a family. Homo sapiens were exceptional hunter-gatherers when times were good; there is new evidence suggesting that the newcomers when fi rst in Europe outbred the Neanderthals by a factor to ten to one. But even so, human population was small and the world very big.

It is not hard to see that such population fi gures mean very slow cultural change. Greatly accelerated though man’s progress in the Old Stone Age may be and much more versatile though he is becoming, he is still taking thousands of years to transmit his learning across the barriers of geography and social division. A man might, after all, live all his life without meeting anyone from another group or tribe, let alone another culture. The divisions which already existed between different groups of Homo sapiens open a historical era whose whole tendency was towards the cultural distinction, though in no way isolation, of one group from another, and this was to increase human diversity until reversed by technical and political forces in very recent times.

About the groups in which Upper Palaeolithic man lived there is still much unknown. What is clear is that they were both larger in size than in former times and also more settled. The earliest remains of buildings come from the hunters of the Upper Palaeolithic who inhabited what are now the Czech and Slovak republics and southern Russia. In about 10,000 BCin parts of France some clusters of shelters seem to have contained anything from 400to 600people, but judging by the archaeological record, this was unusual. Something like the tribe probably existed, therefore, though about its organization and hierarchies it is virtually impossible to speak. All that is clear is that there was a continuing sexual specialization in the Old Stone Age as hunting grew more elaborate and its skills more demanding, while settlements provided new possibilities of vegetable gathering by women.

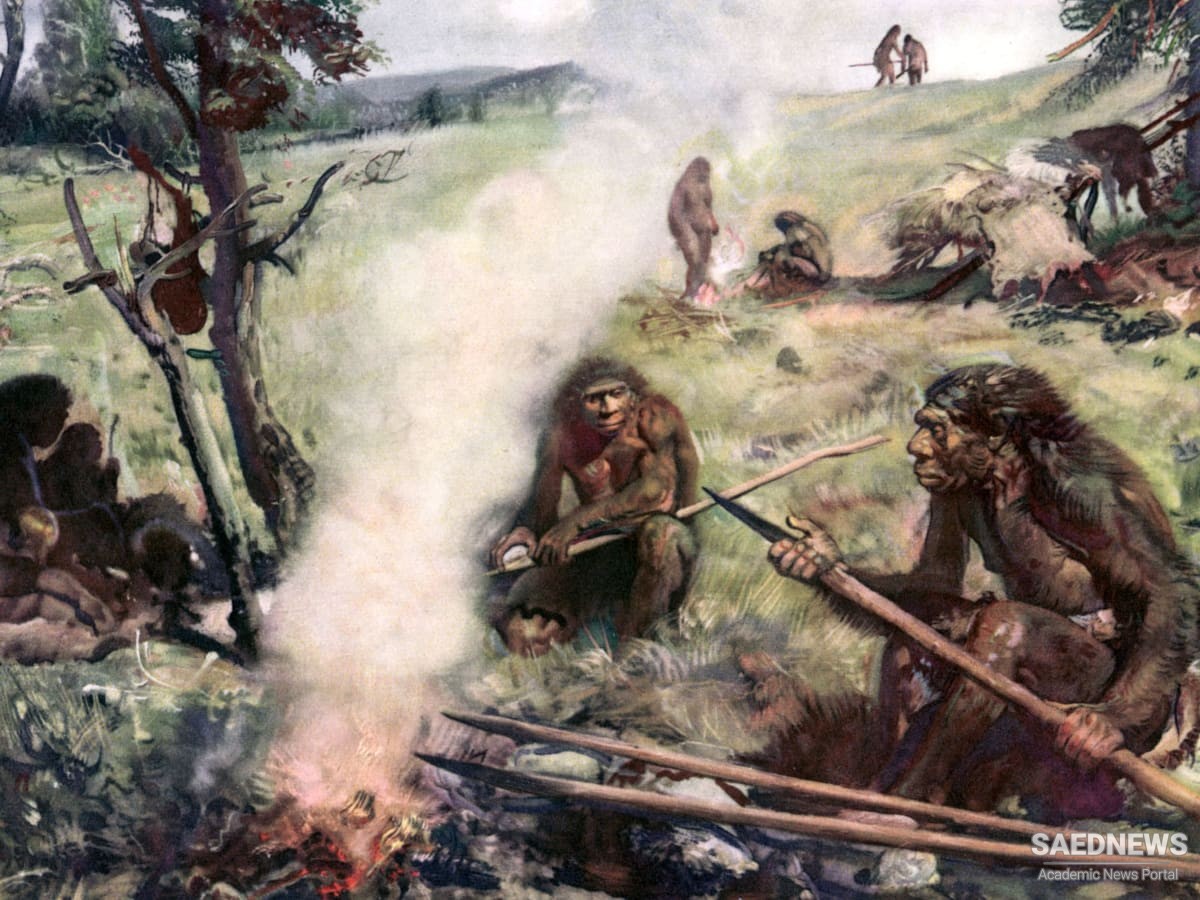

Cloudy though its picture is, none the less, the earth at the end of the Old Stone Age is in important respects one we can recognize. There were still to be geological changes (the English Channel was only to make its latest appearance in about 7000 BC , for example), but we have lived in a period of comparative topographical stability which has preserved the major shapes of the world of about 9000 BC . That world was by then fi rmly the world of Homo sapiens. The descendants of the primates who came out of the trees had, by the acquisition of their tool-making skills, by using natural materials to make shelters and by domesticating fire, by hunting and exploiting other animals, long achieved an important measure of independence from some of nature’s rhythms.

This transformation had brought them to a high enough level of social organization to undertake important co-operative works. Their needs had provoked economic differentiation between the sexes. Grappling with these and other material problems had led to the transmission of ideas by speech, to the invention of ritual practices and ideas which lie at the roots of religion, and, eventually, to a great art. It has even been argued that Upper Palaeolithic man had a lunar calendar. Man as he leaves prehistory is already a conceptualizing creature, equipped with intellect, with the power to objectify and abstract. It is very diffi cult not to believe that it is this new strength which explains the last and greatest stride in prehistory, the invention of agriculture.

Human Continuous Need for Convenience and Technological Development

Human Continuous Need for Convenience and Technological Development