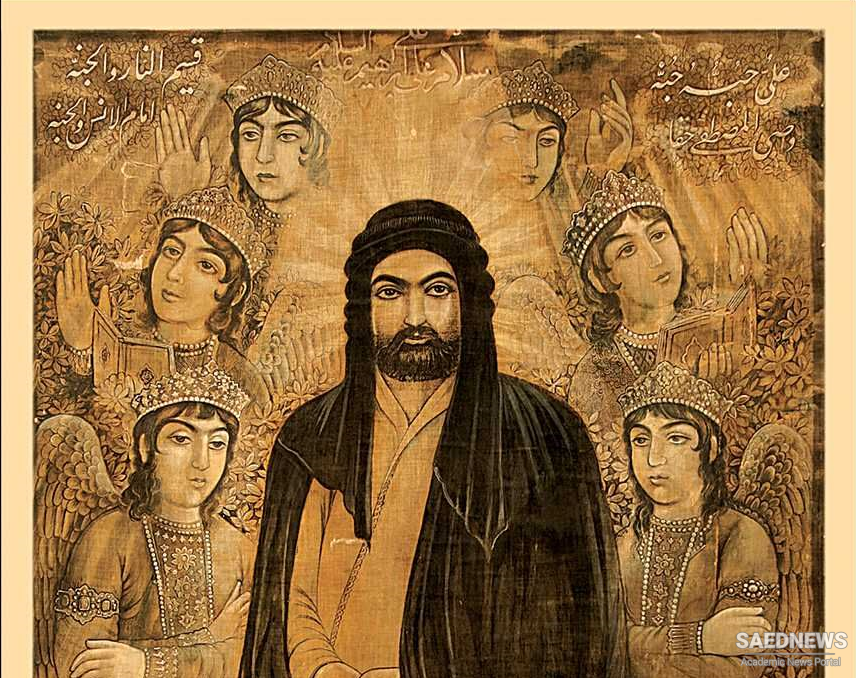

The dominant theme of Shia Islam is clearly and indisputably the lmamate, an institution of a succession of charismatic figures who dispense true guidance in comprehending the esoteric sense of prophetic revelation. Concepts of the Imamate have varied widely, not only with rega.rd to the identity and number of the Imams, but also with respect to the modus operandi and extent of their guidance of the community. Recent research has established that the Twelve Imams now recognized by the branch of Shi'ism dominant in Iran and represented elsewhere by minority groups were not all in their lifetimes the leaders of a sharply defined following that stood aside from the main body of the Muslim community. The messianic hopes attached to charismatic leaders in both Umayyad and Abbasid times did not rest solely on the descendants of the Prophet through his daughter Fatima and his cousin 'Ali: uprisings took place in the name of, among others, Hanafiya, a son of 'Ali by another wife.• Moreover, both activist and quietist attitudes to prevailing authority could be deduced from the Imami belief, but it is clear that the latter came gradually to dominate the mainstream of Shi'ism, leaving its trace also on the Safavid and post-Safavid Shi'ism of Iran. Insofar as any attitude to the state and existing authority can be deduced from the teachings of the Jmams, it is one that combines a denial of legitimacy with a quietistic patience and abstention from action. The Imam Jafar Al Sadiq, sixth in the succession and from whom originates so much of Imami hadith (traditions concerning the sayings and deeds of the Prophet and the Imams), recommended to his followers total abstention from even so much as verbal dispute with their opponents (Religion and State in Iran 1785-1906 : The Role of the Ulama in the Qajar Period).

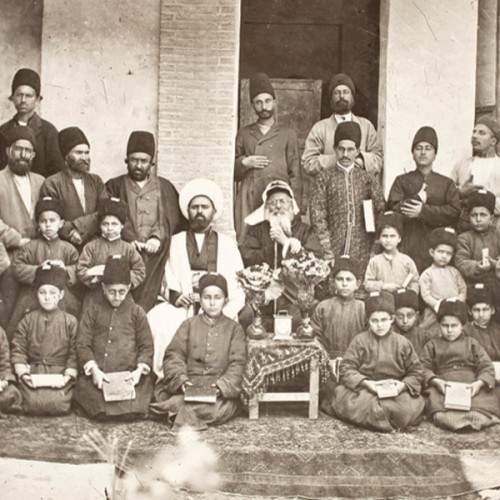

Social Hierarchical Life, Inequity and Modern Cultural Identity in Iran

Social Hierarchical Life, Inequity and Modern Cultural Identity in Iran