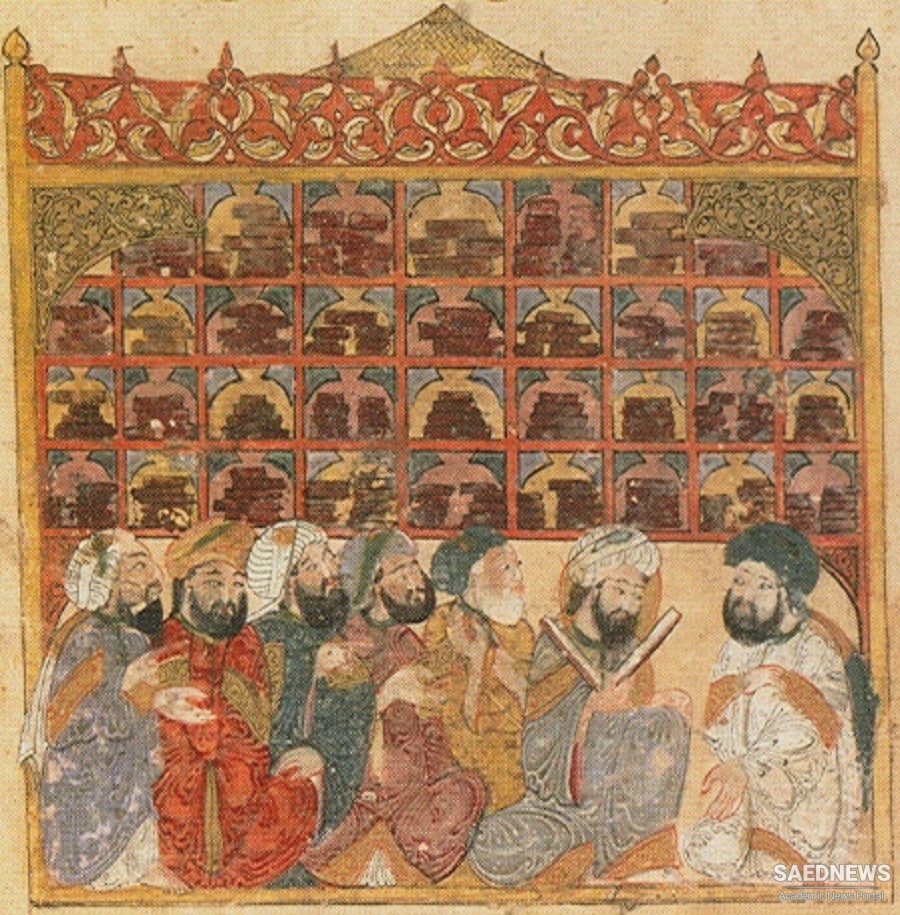

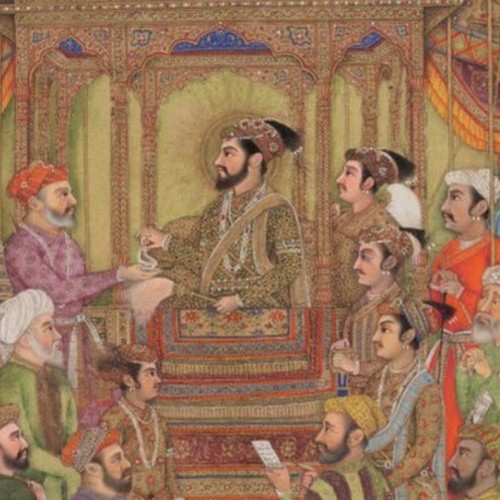

Should an Arab governor in Persia possess an interest in science and scholarship, he would engage on the level of culture at most with Arabic poetry or religious affairs, although such reports may be no more than courtly hyperbole. The importance of the school of medicine in Gondēshāpūr, which could look back on a long tradition dating from the Sasanid era, was in continuous decline at this time. Texts which had been translated into Middle Persian here and elsewhere were translated into Arabic not at the place of their origin but in Mesopotamia. Consequently they, as well as translations from Syriac and Greek, contributed to the emerging Islamic scholarship, which included natural history. They did not, however, stimulate Persian intellectual life. This did not really change until the tenth century. Nishapur had indeed been a centre of scholarship before this. The grammatical, historiographical and genealogical research carried out by the followers of the Shuʿūbīya had developed a high degree of academic understanding. However, it was only under the Samanids that an independent cultural life received real support; only then that colleges, for theology in particular, but also for the religious law connected with it, were founded in the East while the intellectual development of the west and southwest of the country, such as in Fars, lagged behind (Source: Early Islam and Persia).

Early Islamic Centuries and Intellectual Shining of Persian Culture

Early Islamic Centuries and Intellectual Shining of Persian Culture