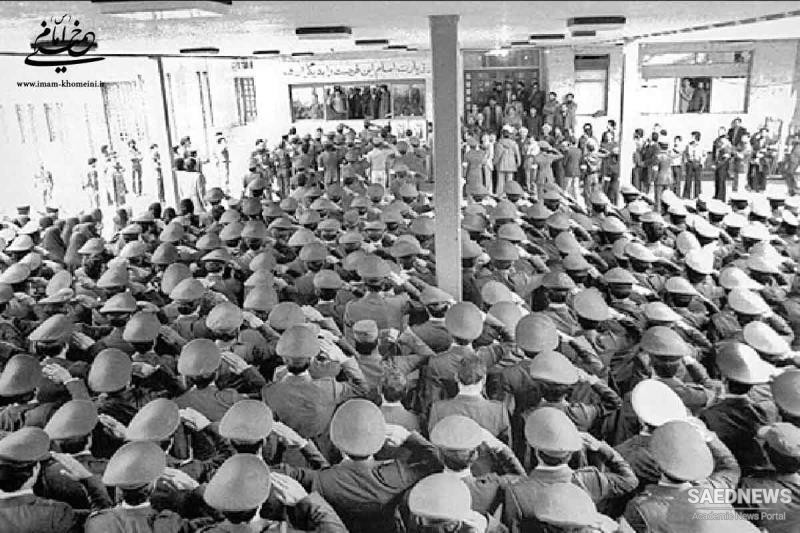

Significantly for what was to follow, 800 air force technicians from the aircraft servicing organization known as the Homafaran had defected together to the revolutionary movement in the second half of January. Attempts to discipline them were lost in the general chaos, and they became an important militant element in the revolutionary movement, comparable with the Kronstadt sailors in the February and October revolutions of 1917 in Russia. Most of them were noncommissioned officers, specialists with a grievance because, although technically qualified, they felt their promotion within the service was blocked by a structure that favoured socially and politically privileged officers trained in cadet college – in its way a situation that echoed the wider disposition of socially insecure petit- bourgeois classes toward the revolutionary movement. 15 But a number of air force officers and cadets joined them too. After 5 February, with two rival governments in the country, the leaders of the armed forces were in an awkward position. Many of the senior officers knew that some of their number were negotiating with Bazargan and/or clerics close to Khomeini, like Ayatollah Beheshti; as were the Americans, through their embassy. General Huyser, who had wanted to keep open the option of a military coup, had left the country. It seems that, although the account of this episode in his own memoirs is quite vague, 16 General Hosein Fardust, head of the supervisory Special Intelligence Bureau under the Shah, may have been instrumental between 5and 9 February in steering other generals away from action against Bazargan’s nascent government. Having been a childhood friend of the Shah, Fardust seems to have sided with the Islamic regime in 1979and controversially, afterwards helped the new SAVAMA , later renamed the Ministry of Intelligence and Security ( VEVAK ), the ugly phoenix that rose out of the remnants of the Shah’s infamous secret police, SAVAK .

Iranians Are Not Going to Be Used for Trial of Foreign Vaccines, Iran President Hassan Rouhani Says

Iranians Are Not Going to Be Used for Trial of Foreign Vaccines, Iran President Hassan Rouhani Says