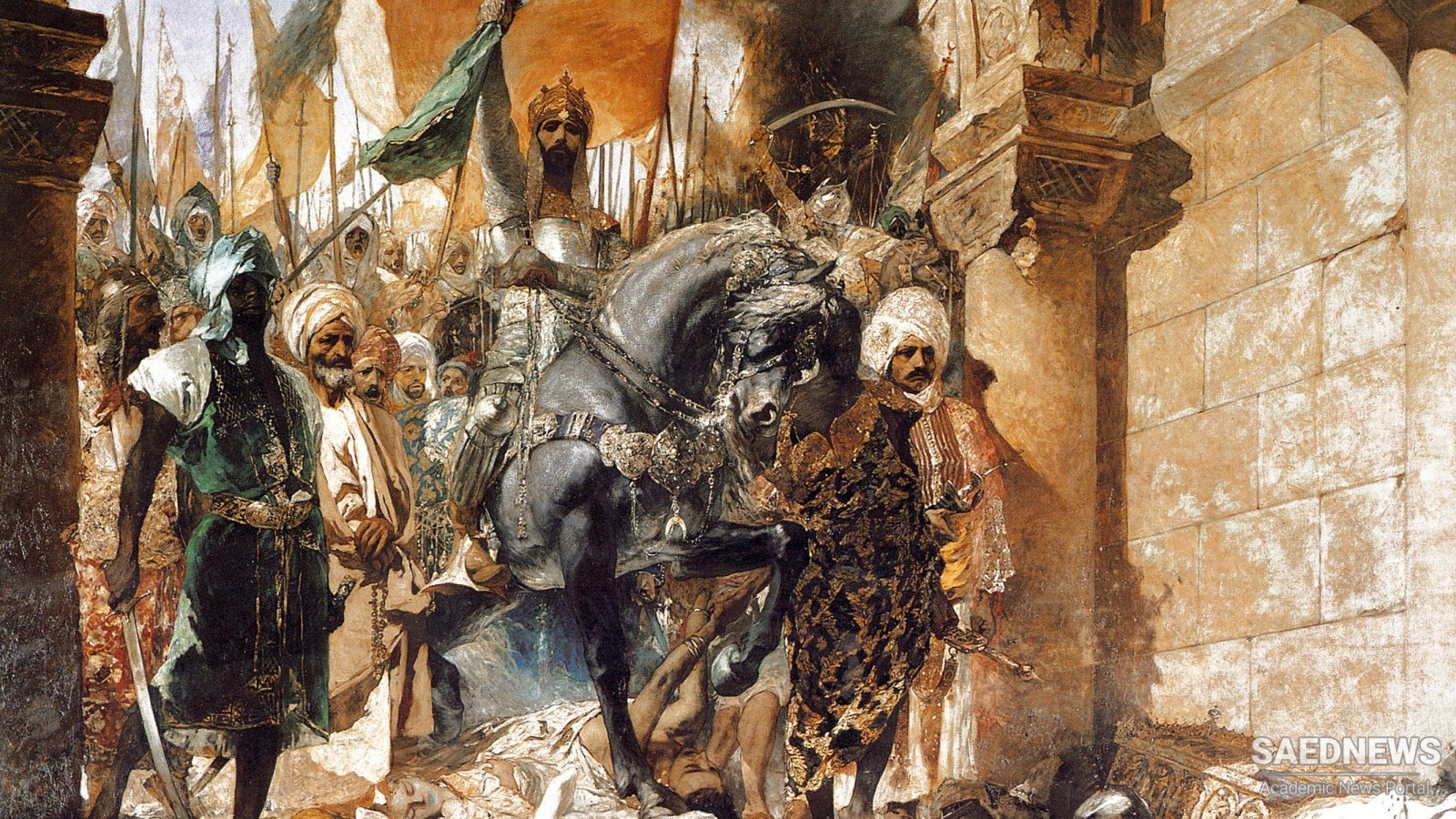

The Arab conquests of the first Islamic century created in a few decades a great empire of unprecedented size. The Prophet himself in his own lifetime had united the Arabian peninsula under a Pax Islamica. The threatening movement of apostasy after his death (632) was stemmed by the first caliph Abu Bakr through the call to wage war against the unbelievers – with the aim of booty in this world and eternal salvation in the next.

Not only the Arab tribes but also those of the neighbouring areas of Syria and Mesopotamia (where until the sixth century Christian Arab dynasties had served as the buffer states of Eastern Byzantium and Iran against attacks from Inner Arabia) embraced the new movement and advanced in the name of God against the empires of Byzantium and Sasanian Persia, which were unprepared from both the military and the political point of view. Under Abu Bakr’s great successor, Umar, Damascus fell (635), and soon afterwards the other territories of the Byzantine Empire in Syria and Egypt fell too (Alexandria 642). At the same time the Persians in Iraq had to undergo severe defeats (636 at Qadisiyya).

The decisive battle of Nihawand (641) cleared the way across the Iranian plateau. In the year 649 the empire of the Sasanian kings came completely to an end, and two years later the fugitive Yazdagird III was killed in Khurasan. The caliphs of the Umayyad dynasty (from 661), after emerging triumphant from two civil wars, renewed a policy of expansion. Arab armies poured out of Iraq to the east and the north (as far as adharbayjan), and westwards from Egypt. In the year 711 they finally reached Spain, Transoxiana and India.

The consequences of Islamisation and the effects of Arabisation were very different from region to region; everywhere Islamisation was a very slow-moving process. The centres of power, which were at first determined by military necessity, shifted and multiplied under the pressure of political change: the transition from tribal alliance to a centrally-organised State, and tensions between sedentary, nomadic and newly-settled population as well as between Arab and newly-converted non-Arab Muslims. Everywhere the broad outlines of later disintegration can already be seen in the geographical and geopolitical structure of the emerging empire.

Each of the classic regions of Islam had its own individual history: the Arabian peninsula; the Fertile Crescent: Egypt, Syria and the Jazira, the ‘island’ between the upper Euphrates and the Tigris; the Islamic West (Maghrib): North Africa and Spain (al-Andalus), Iraq and Iran with the provinces in the east: Khurasan, Khwarazm on the Oxus and Transoxiana, Sistan and Sind. Even after the collapse of the caliphal empire other areas came under Muslim rule: Anatolia and India, South-East Asia and Inner Africa.

Second Pilar of Islam: Salah

Second Pilar of Islam: Salah