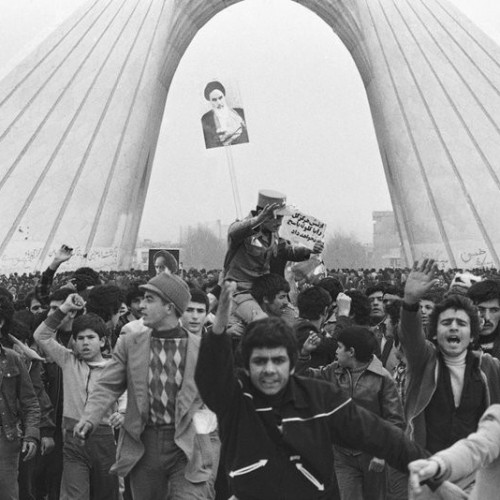

In January 1978, incensed by what they considered to be slanderous remarks made against Khomeini in Eṭṭelāʿāt, a Tehrān newspaper, thousands of young madrasah (religious school) students took to the streets. They were followed by thousands more Iranian youth—mostly unemployed recent immigrants from the countryside—who began protesting the regime’s excesses. The shah, weakened by cancer and stunned by the sudden outpouring of hostility against him, vacillated between concession and repression, assuming the protests to be part of an international conspiracy against him. Many people were killed by government forces in anti-regime protests, serving only to fuel the violence in a Shiʿi country where martyrdom played a fundamental role in religious expression. Fatalities were followed by demonstrations to commemorate the customary 40-day milestone of mourning in Shiʿi tradition, and further casualties occurred at those protests, mortality and protest propelling one another forward. Thus, in spite of all government efforts, a cycle of violence began in which each death fueled further protest, and all protest—from the secular left and religious right—was subsumed under the cloak of Shiʿi Islam and crowned by the revolutionary rallying cry Allāhu akbar (“God is great”), which could be heard at protests and which issued from the rooftops in the evenings. The violence and disorder continued to escalate. On September 8 the regime imposed martial law, and troops opened fire against demonstrators in Tehrān, killing dozens or hundreds. Weeks later, government workers began to strike. On October 31, oil workers also went on strike, bringing the oil industry to a halt. Demonstrations continued to grow; on December 10, hundreds of thousands of protesters took to the streets in Tehrān alone (Source: Britanica).

Islamic Revolution: Towards an Understanding of Roots and Causes

Islamic Revolution: Towards an Understanding of Roots and Causes