There is a tradition of Imām Ridā (‘a) in which he says approximately the following: “An upright, protecting, and trustworthy imām is necessary for the community in order to preserve it from decline,” and then reasserts that the fuqahā are the trustees of the prophets (‘a). Combining the two halves of the tradition, we reach the conclusion that the fuqahā must be the leaders of the people in order to prevent Islam from falling into decline and its ordinances from falling into abeyance. Indeed it is precisely because the just fuqahā have not had executive power in the lands inhabited by Muslims and their governance has not been established that Islam has declined and its ordinances have fallen into abeyance. The words of Imām Ridā have fulfilled themselves; experience has demonstrated their truth.

Has Islam not declined? Have the laws of Islam not fallen into disused in the Islamic countries? The penal provisions of the law are not implemented; the ordinances of Islam are not enforced; the institutions of Islam have disappeared; chaos, anarchy, and confusion prevail does not all this mean that Islam has declined? Is Islam simply something to be written down in books like al-Kāfi57 and then laid aside? If the ordinances of Islam are not applied and the penal provisions of the law are not implemented in the external world so that the thief, the plunderer, the oppressor, and the embezzler all go unpunished while we content ourselves with preserving the books of law, kissing them and laying them aside (even treating the Qur’an this way), and reciting Yā-Sin on Thursday nights58 can say that Islam has been preserved?

Since many of us did not really believe that Islamic society must be administered and ordered by an Islamic government matters have now reached such a state that in the Muslim countries, not only does the Islamic order not obtain, with corrupt and oppressive laws being implemented instead of the laws of Islam, but the provisions of Islam appear archaic even to the ‘ulamā. So when the subject is raised, they say that the tradition: “The fuqahā are trustees of the prophets” refers only to the issuing of juridical opinions. Ignoring the verses of the Qur’an, they distort in the same way all the numerous traditions that the scholars of Islam are to exercise rule during the Occultation. But can trusteeship be in this manner? Is the trustee not obliged to prevent the ordinances of Islam from falling into abeyance and criminals from going unpunished? To prevent the revenue and income of the country from being squandered, embezzled or misdirected?

It is obvious that all of these tasks require the existence of trustees, and that it is the duty of the fuqahā to assume the trust bequeathed to them, to fulfill it in a just and trustworthy manner. The Commander of the Faithful (‘a) said to Shurayh: “The seat [of judge] you are occupying is filled by someone who is a prophet (‘a), the legatee of a prophet, or else a sinful wretch.”60 Now since Shurayh was neither a prophet nor the legatee of a prophet, it follows that he was a sinful wretch occupying the position of judge. Shurayh was a person who occupied the position of judge in Kūfah for about fifty or sixty years. Closely associated with the party of Mu‘āwiyah, Shurayh spoke and issued fatwās61 in a sense favorable to him, and he ended up rising in revolt against the Islamic state. The Commander of the Faithful (‘a) was unable to dismiss Shurayh during his rule, because certain powerful figures protected him on the grounds that Abu Bakr and ‘Umar had appointed him and that their action was not to be controverted. Shurayh was thus imposed upon the Commander of the Faithful (‘a), who did, however, succeed in ensuring that he abided by the law in his judgment.

It is clear from the foregoing tradition that the position of judgment may be exercised only by a prophet (‘a) or by the legatee of a prophet. No one would dispute the fact that the function of judge belongs to the just fuqahā, in accordance with their appointment by the Imāms (‘a). This unanimity contrasts with the questions of the governance of the faqīh: some scholars, such as Narāqi,62 or among more recent figures, Nā’ini, regard all of the extrinsic functions and tasks of the Imāms (‘a) as devolving upon the faqih, while other scholars do not. But there can be no doubt that the function of judging belongs to the just fuqahā; this is virtually self-evident.

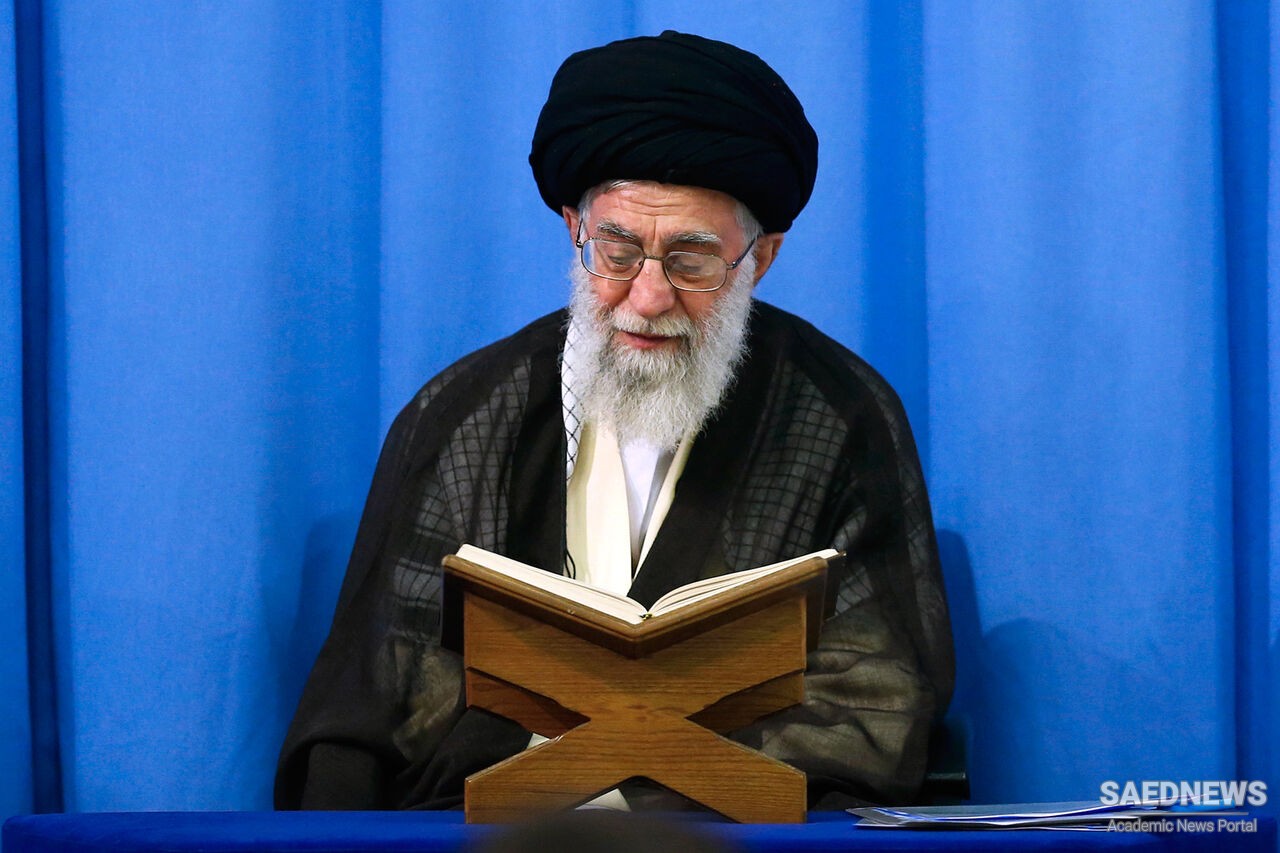

Authorized Jurist the Lighthouse of Islamic Society

Authorized Jurist the Lighthouse of Islamic Society