German-born American composer Kurt Julian Weill created a revolutionary kind of opera of sharp social satire in collaboration with the writer Bertolt Brecht. Weill studied privately with Albert Bing and at the Staatliche Hochschule für Musik in Berlin with Engelbert Humperdinck. He gained some experience as an opera coach and conductor in Dessau and Lüdenscheid (1919–20). Settling in Berlin, he studied (1921–24) under Ferruccio Busoni, beginning as a composer of instrumental works. His early music was expressionistic, experimental, and abstract. His first two operas, Der Protagonist (one act, libretto by Georg Kaiser, 1926) and Royal Palace (1927), established his position, with Ernst Krenek and Paul Hindemith, as among Germany’s most promising young opera composers.

Weill’s first collaboration as composer with Bertolt Brecht was on the singspiel (or “songspiel,” as he called it) Mahagonny (1927), which was a succès de scandale at the Baden-Baden (Germany) Festival in 1927. This work sharply satirizes life in an imaginary America that is also Germany. Weill then wrote the music and Brecht provided the libretto for Die Dreigroschenoper (1928; The Threepenny Opera), which was a transposition of John Gay’s Beggar’s Opera (1728) with the 18th-century thieves, highwaymen, jailers, and their women turned into typical characters in the Berlin under�world of the 1920s. This work established both the topical opera and the reputations of the composer and librettist. Weill’s music for it was in turn harsh, mordant, jazzy, and hauntingly melancholy. Mahagonny was elaborated as a full�length opera, Aufstieg und Fall der Stadt Mahagonny (composed 1927–29; “Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny”), and first presented in Leipzig in 1930. Widely considered Weill’s masterpiece, the opera’s music showed a skillful synthesis of American popular music, ragtime, and jazz.

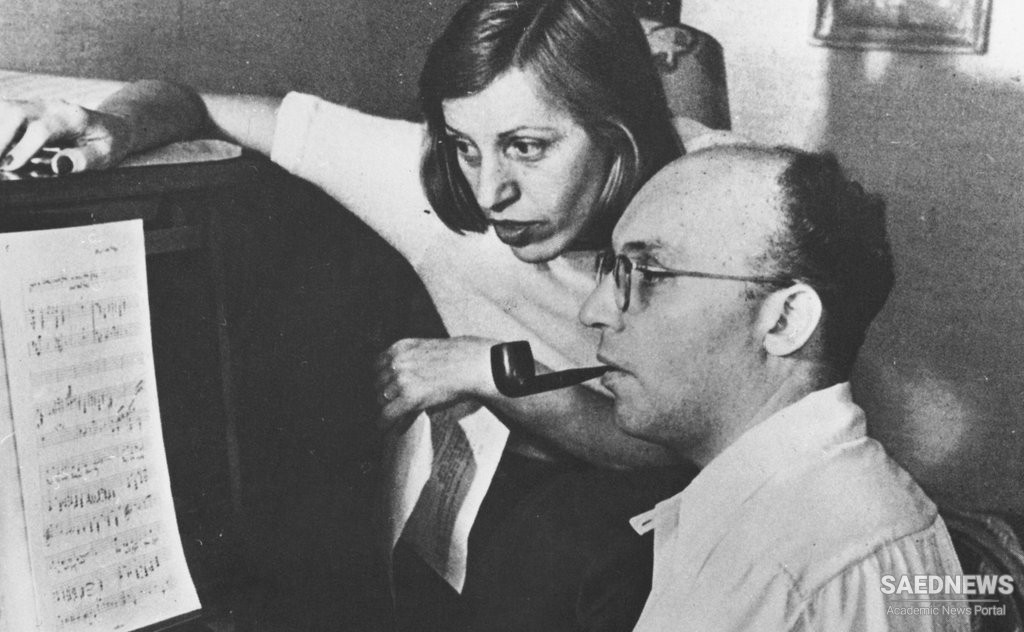

Weill’s wife, the actress Lotte Lenya (married 1926), sang for the first time in Mahagonny and was a great success in it and in Die Dreigroschenoper. These works aroused much controversy, as did the students’ opera Der Jasager (1930; “The Yea-Sayer,” with Brecht) and the cantata Der Lindberghflug (1928; “Lindbergh’s Flight,” with Brecht and Hindemith). After the production of the opera Die Bürgschaft (1932; “Trust,” libretto by Caspar Neher), Weill’s political and musical ideas and his Jewish birth made him persona non grata to the Nazis, and he left Berlin for Paris and then for London. His music was banned in Germany until after World War II.

Weill and his wife divorced in 1933 but remarried in 1937 in New York City, where he resumed his career. He wrote music for plays, including Paul Green’s Johnny Johnson (1936) and Franz Werfel’s Eternal Road (1937). His operetta Knickerbocker Holiday appeared in 1938 with a libretto by Maxwell Anderson, followed by the musical play Lady in the Dark (1941; libretto and lyrics by Moss Hart and Ira Gershwin), the musical comedy One Touch of Venus (1943; with S.J. Perelman and Ogden Nash), the musi�cal version of Elmer Rice’s Street Scene (1947), and the musical tragedy Lost in the Stars (1949; with Maxwell Anderson). Weill’s American folk opera Down in the Valley (1948) was much performed. Two of his songs, the “Morität” (“Mack the Knife”) from Die Dreigroschenoper and “September Song” from Knickerbocker Holiday, have remained popular. Weill’s Concerto for violin, woodwinds, double bass, and percussion (1924), Symphony No. 1 (1921; “Berliner Sinfonie”), and Symphony No. 2 (1934; “Pariser Symphonie”), works praised for their qualities of invention and compositional skill, were revived after his death.

Duke Ellington

Duke Ellington