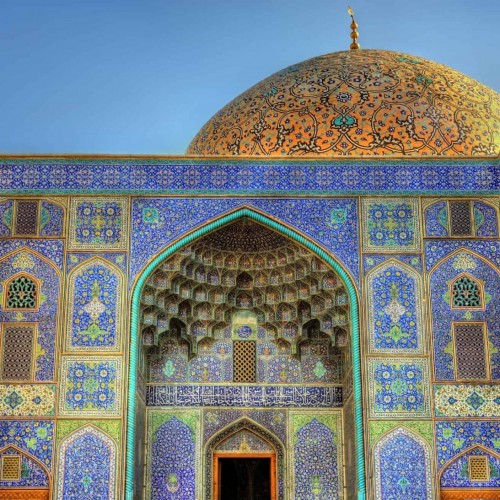

In Esfahan, Shah Abbas embarked on a concerted campaign to build a magnificent city with ornate palaces, mosques, a bazaar, and a grand central square. For his own and his subjects’ viewing pleasure, he also built a polo grounds and a carnival arena. Shi‘ite scholars were brought in from Syria, Iraq, and Arabia to help teach and propagate the new religion, and great mosques and religious schools (madresahs) were built in the major cities.

Despite the zeal and determination of the dynasty’s founder, Ismail, and the splendor of the royal court and the capital under Shah Abbas, the Safavids were never quite able to consolidate their rule throughout much of the country. Soon they were to confront strong resistance from various nomadic tribes and from other local rulers. More importantly, they were challenged in their Shi‘ite legitimacy and interpretation by an increasingly independent and vocal class of clerics. Significantly weakened, by the late 1600s and early 1700s Safavid rule was being threatened nearly everywhere outside the capital city of Esfahan. According to the historian Ira Lapidus, “[T]he Safavid state remained a court regime in a fluid society in which power was widely dispersed among competing tribal forces. These forces would in the end overthrow the dynasty.” The end came in the 1720s. Esfahan was captured in 1722 by one of the uymaqs, the Ghalzai Afghans, who then overthrew the dynasty in 1726.

A period of competing, local dynasties followed, none quite capable of achieving meaningful territorial hegemony beyond its immediate areas of control. Nevertheless, one of these competing groups, the Qajars, was able to establish a precarious suzerainty over significant parts of Iran beginning in 1779, giving rise to a dynasty by the same name. Although their hold on power remained tenuous throughout, the Qajars did manage to last until 1925.

Persia's Regional Policy in Late Middle Ages: Safavids

Persia's Regional Policy in Late Middle Ages: Safavids