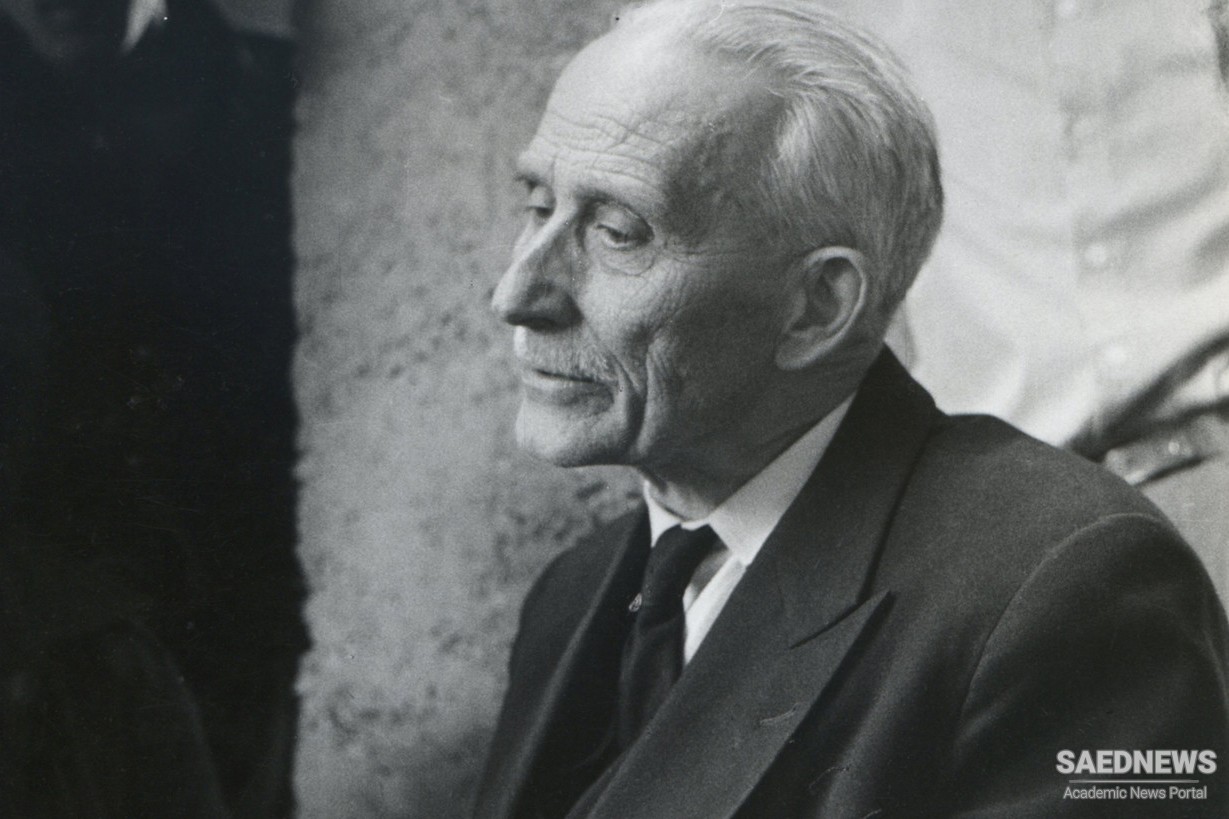

In 1922 he submitted his two requisite doctoral theses on al-Ḥallāj and early Islamic mysticism to the University of Paris; published in two volumes as La passion d'al-Hosayn-ibn-Mansour al'Hallâj, martyr mystique de l'Islam exécuté à Bagdad le 26 mars 922 (1922), his thèse principale has since become a classic. A second, greatly enlarged edition appeared posthumously (1975). In 1926 Massignon was elected professor of sociology and sociography of Islam at the Collège de France in Paris, and in 1933 he was appointed director of studies for Islam at the École Pratique des Hautes Études, also in Paris, in the section of sciences religeuses. In the same year he was elected a member of the new Academy of the Arabic Language in Cairo, where he spent several weeks working each winter.

Born and raised a Roman Catholic, Massignon underwent a particular inner experience in 1908, which he spoke of as his "conversion." As a result he became once more a loyal member of the Roman Catholic church, increasingly with a spiritual vocation with regard to Islam. In 1931 he became a third-order Franciscan, and in 1934 he founded the Badaliya sodality, the members of which were inspired by compassion and devoted themselves to "substitution" for their Muslim brethren. (The idea of substitution involves one person's taking another's suffering upon himself.) After joining the Greek Catholic (Uniate) church in 1949, Massignon was ordained a priest on January 28, 1950, in Cairo. Even though ordination in this church is possible for a married man, as Massignon was, the Vatican imposed the condition that Massignon's priesthood, which turned out to be an essential element in his spiritual life and vocation, should remain secret. Even after his retirement in 1954 Massignon continued to take an active part in defending victims of violence (e.g., Palestinians and Algerians) until his death on October 31, 1962, in Paris.

Massignon's work is the accomplishment and creation of a mind of remarkable stature, illuminated by flashes of genius but capable of being carried away, to the verge of aberration, by ideas. A reader is confronted with the difficult task of recognizing the particular perspectives in which Massignon interpreted his subject matter and correcting them according to the scholarly criteria of factual interpretation and validity. If Massignon's unique spiritual commitments made his oeuvre one of the richest in the whole field of Islamic studies, one must recognize that it drew its strength from an existential position unrelated to scholarship. While its originality deserves respect and admiration, the lack of scholarly standards must also be recognized.

Massignon's monumental study of al-Ḥallāj will probably remain his lasting contribution to the study of Islam and religion generally. It is more than a careful historical reconstruction of facts and bygone spiritual worlds. It is the record of a spiritual encounter in which a scholar fascinated by a religious truth meets a mystic of the past in whom this truth is recognized. Were it not for Massignon, such spiritual dimensions might not have been revealed in al-Ḥallāj, but to what extent the spiritual al-Ḥallāj discovered by Massignon is the result of valid hermeneutics of the texts and not a spiritual creation born of the religious needs and passions of Massignon as a person is a question that haunts the reader. Massignon's inner experiences of May and June 1908, as a result of which he received a "new life" of adoration and witnessing, welded together for him the figures of al-Ḥallāj and Christ, the existence of God and the experience of divine grace. Thereafter, al-Ḥallāj, Christ, and their witness Louis Massignon could no longer be separated either by Massignon himself or by those studying his reconstruction of the Hallajian drama.

Massignon's second contribution is his precise technical investigation of the religious, particularly the mystical, vocabulary in Islam. Apart from his claim that the spiritual realities to which these words allude can be rediscovered through the study of the words themselves—and that the researcher at a certain moment finds himself confronted precisely with that reality to which the mystic testifies—his technical achievements were enormous and have inspired such scholars as Paul Nwyia to proceed with their researches on religious vocabulary along the same line.Massignon's third major contribution is to have succeeded, in a period of ever-growing specialization, in retaining a global view of what may be called the world of Islam in its various material and spiritual dimensions. He could see it all as forming a meaningful whole under the sign of Islam, just as he could see Islam as meaningful in the perspective of al-Ḥallāj. Thus his "minor works," collected in Opera minora (1963), include articles on widely varying subjects. Throughout these articles we find a complex hermeneutics of texts, personalities, and ideas directed to revealing not only their literary, historical, and semantic meanings but also their spiritual intentions. In his hermeneutical research, Massignon showed both an immense erudition and an extraordinary sensitivity, particularly to religious and devotional realities. His sensitivity extended to those realities that exist partly in the realm of dreams and partly in that of fact, realities to which the religious mind and what was once commonly called the "Oriental mind" are so attuned.

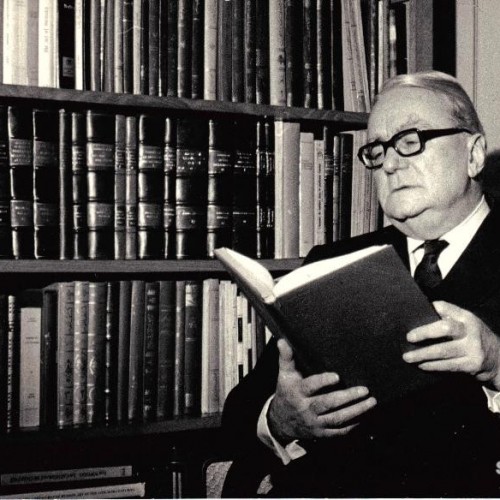

Henry Corbin the Discoverer of Persian Spiritual Gems

Henry Corbin the Discoverer of Persian Spiritual Gems