It was instrumental in organizing the Tabriz neighborhood militias into an effective fighting force. A large numbers of émigrés revolutionaries from among the Muslims, Armenians and Georgians of Baku and Tiflis also joined the resistance. The Baku Social Democratic Party, which included Iranian émigrés, and Russian Social Democrats also supported Tabriz with manpower, money, weapons, and tactical advice.

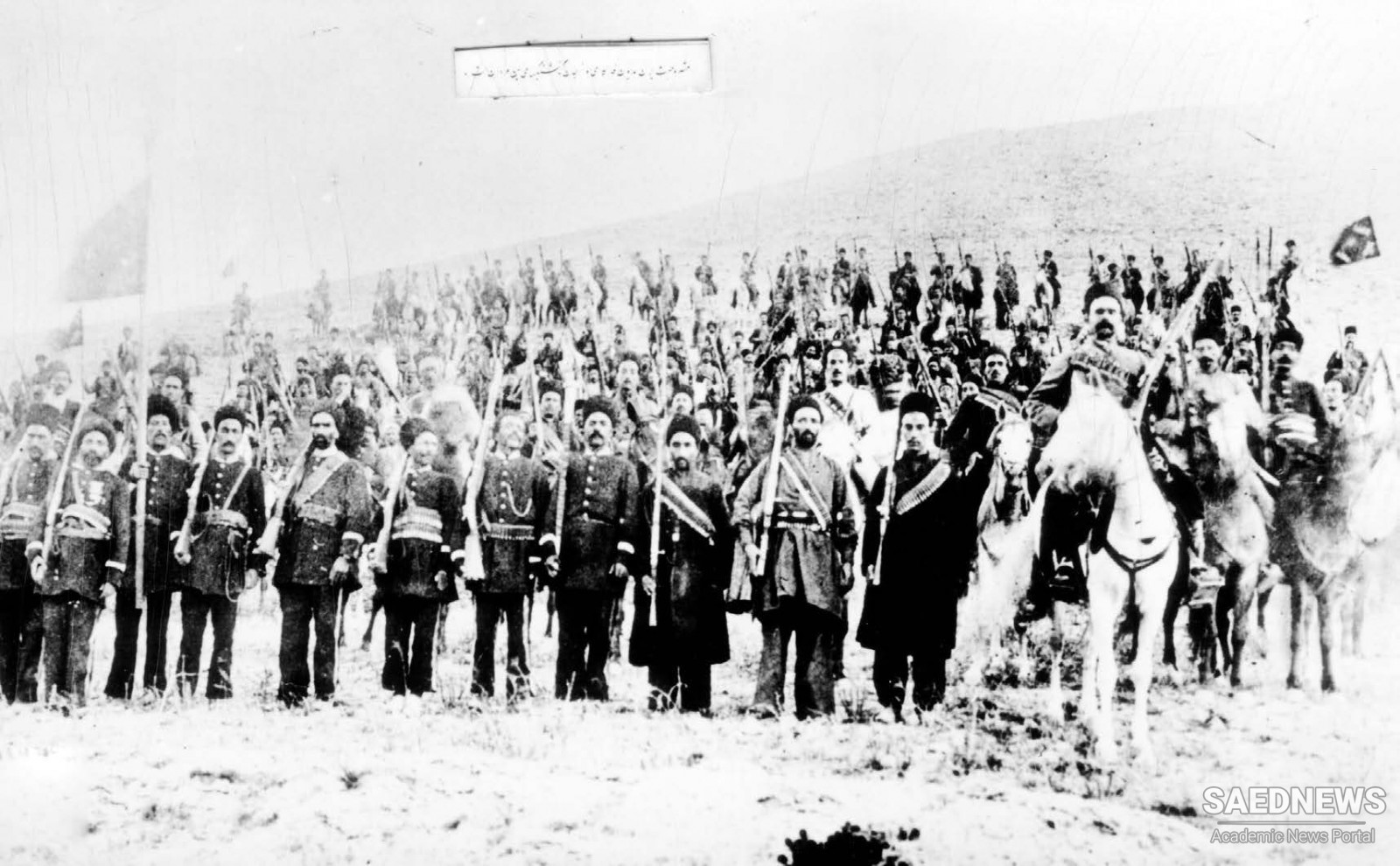

Sattar Khan (1866–1914), a former horse trader and reformed luti, was a natural leader whose gift for urban warfare complemented his habit of extorting “contributions” for the national cause. Access to the government arsenal inside the Tabriz citadel allowed the fighters, who had adopted the general name Fada’i (devotee), to indulge in a cache of weapons, ammunitions, and field guns. Using local expertise, and often improvising, they fortified barricades, gates, and other strategic locations around constitutionalist wards. Beginning with a handful of devotees, Sattar endured not only enemy fire but also defection from his own ranks. Motivated by neighborhood rivalry, personal gain, and a code of honor, he did not easily accept defeat. Though at the outset the Fada’is were primarily motivated by neighborhood loyalties, over time they cultivated greater appreciation for value of constitutionalism.

For the Tehran coup to succeed, subduing the Tabriz rebels seemed essential, and the shah mustered all the forces he had to achieve this objective. At the outset, and at an enormous cost, he mobilized several regiments from Azarbaijan and elsewhere and sent off to Tabriz the Shahseven irregular cavalry. Later, Cossack reinforcements were dispatched. He financed and gave his blessings to the Tabriz Islamic Anjoman and its affiliated Usuli ulama in the royalist wards. Under the pretext of protecting foreign nationals, the Russian consulate in the city also collaborated with the shah.

The government forces almost succeeded in their objective to isolate Sattar, Baqer, and a handful of their cohorts. But as time passed, fortunes changed once the Fada’is learned how to conduct urban warfare. Government troops in and around the city relentlessly pounded their positions and engaged in pitched battles in narrow streets and in orchards and adjacent villages. Casualties were heavy on both sides, throughout the eleven months amounting to at least five thousand dead and many more injured and displaced. Parts of Tabriz were ruined and villages at the outskirts and along the trade routes in every direction suffered. Innocent citizens were plundered and killed, and merchandise in the Tabriz bazaar and in a new shopping arcade was looted or destroyed by the troops, armed brigands, and by the constitutionalist partisans.

At first, looting and extortion were about the only means of survival for the starving Qajar army and the revolutionary fighters. Later, however, the revolutionary leadership enforced greater discipline among their troops and gradually improvised a chain of command, including fighting units with regular shifts, detachments for special tasks, logistics, a camp kitchen, medical aids (including a camp hospital), makeshift communication and intelligence, a minimum wage, and even a uniform Fada’i karakul cap. These improvements allowed the Tabriz fighters to defend their ground, but they barely made any physical advances between July and October 1908. What was at stake, however, was a symbolic resistance against the Tehran regime that neither the shah nor his Russian backers could afford to ignore. When a new round of fighting began in March 1909 after a three-month lull, the Tabriz fighters enjoyed better finances thanks to a donation committee that had been established to persuade affluent citizens to contribute. They acquired superior weapons, and above all, there was growing moral support within Iran and beyond in the Caucasus and the Ottoman Empire. The Young Turk Revolution that had removed Sultan ‘Abd al-Hamid from power in April 1908 was welcomed by the fighters in Tabriz as much as it was despised by Mohammad ‘Ali Shah in Tehran.

Minor Tyranny and Civil War

Minor Tyranny and Civil War