Together Kuchak Khan and his Jangal resistance would become part of the martyr narrative that permeates Iran’s mythical memory and marks its historical landscape. Born to a family of petty landowners in the provincial capital of Rasht, Kuchak Khan was a student in the local seminary when he first heard and was moved by the message of the Constitutional Revolution.

Following flocks of Iranians to the oil rich-city of Baku and later to the Georgian capital of Tiflis, he was exposed to the revolutionary trends among the Azarbaijanis and Armenians in the Caucasus, and to the émigré merchants, home-brewed revolutionaries, and drifters. On his return to Iran, he joined the Gilan constitutionalists during the civil war of 1908–1909, but in Tehran the euphoria of the 1909 victory quickly gave way to disillusionment as Kuchak Khan witnessed the return to power of the old elites joined by wealthy provincial landowners.

By the time he volunteered in July 1911 to fight against the deposed Mohammad ‘Ali Shah in the battle of Gomish Tappeh north of Astarabad, where he was wounded and captured by Russians, he seemed to have lost hope in the success of the parliamentary process. Upon his release from detention, distraught and penniless, he returned to Rasht, where his anti-Russian activities forced him into hiding from the Russian occupying force.

A devout and austere Muslim, at the outset of the Great War he seems to have been sufficiently enamored of the message of pan-Islamism, which at the time was heavily promoted by the Young Turks regime, to contact the Ottoman and German legations in Tehran. He entertained the idea of organizing a partisan war in the thick forests of his homeland in the province of Gilan.

With little logistical support and even less local backing, Kuchak and a handful of like-minded local supporters managed to mobilize a small guerilla force. By 1914 they had consolidated in and around the village of Pasikhan near Rasht, the birthplace of the fourteenth-century founder of the Noqtavi movement Soon after he was joined by local peasants, artisans, shopkeepers, and petty landowners, but also by journalists, intellectuals, and former revolutionaries. Handsome, charismatic, and witty, yet also easily irritable and fatalistic, the thirty-three-year-old Kuchak Khan founded what is perhaps the twentieth century’s first guerilla movement, with its revolutionary ideology and a semblance of partisan organization .

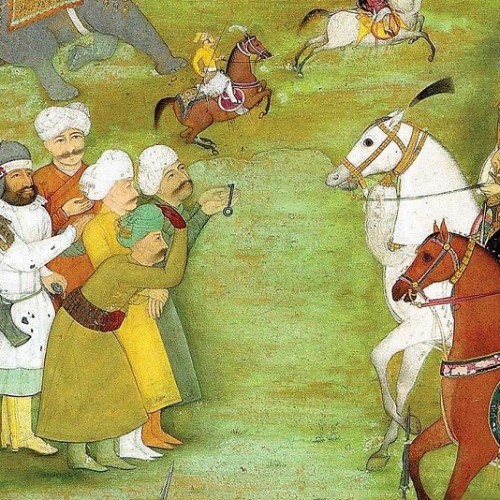

He may also be considered a crucial link between romantic nationalism with a socialist flavor and new interpretations of Islam as an anti-imperialist force. He was dressed in an iconic local outfit of the Galesh peasant of Gilan: a round felt cap, coarse leather shoes, and the thick sleeveless felt jacket worn by the shepherds of the Fuman region. With wild, uncut hair and a massive black beard, the sight of Kuchak and the Jangali fighters was utterly and deliberately divorced from the urbane world from which most of their leaders had come. Posing proudly for cameras, often with their rifles held diagonally across their chest and with bulky rounds of ammunition strapped to their torso, they embodied patriotism and a love affair with firearms. Towering high over his disciples, Kuchak Khan loomed as a prophet in the wilderness, defying occupation and corrupt authorities and seeking to make right all the wrongs his nation had sustained. That he chose a forest (jangal) to launch a partisan war may in part be because of his familiarity with his native terrain but also because of the symbolism that the forest invoked as the birthplace of a salvation movement.

Mutinies, Radical Movements and Fragile Governance

Mutinies, Radical Movements and Fragile Governance