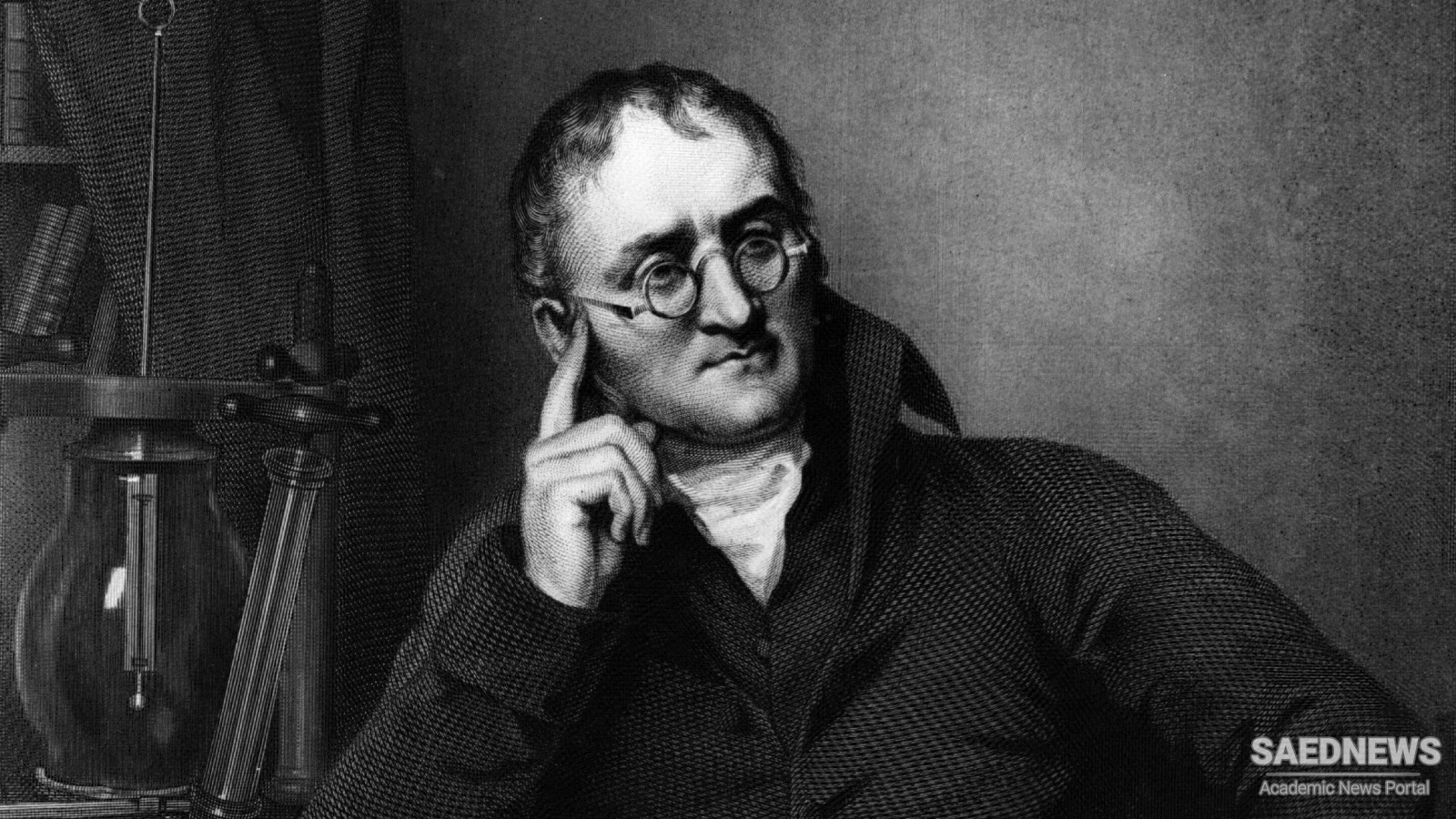

Science historians generally credit the British schoolteacher and chemist John Dalton (1766–1844) with the start of modern atomic theory. In 1803, Dalton suggested that each chemical element was composed of a particular type of atom. He defined the atom as the smallest particle or unit of matter in which a particular element can exist. His interest in the behavior of gases allowed Dalton to quantify the atomic concept of matter. In particular, he showed how the relative masses or weights of different atoms could be determined. To establish his relative scale, he assigned the atom of hydrogen a mass of unity. In so doing, Dalton revived atomic theory and inserted the concept of the atom into the mainstream of modern science. Another important step in the emergence of atomic theory occurred in 1811, when the Italian scientist Amedeo Avogadro (1776–1856) formulated his famous hypothesis that eventually became know as Avogadro’s Law. He proposed that equal volumes of gases at the same temperature and pressure contain equal numbers of molecules. At the time, neither Dalton, Avogadro, nor any other scientist had a clear and precise understanding of the difference between an atom and a molecule. Later in the nineteenth century, scientists recognized the molecule as the smallest particle of any substance (element or compound) as it normally occurs. By the time the Russian scientist Dmitri I. Mendeleyev (1834–1907) published his famous periodic law in 1869, it was generally appreciated within the scientific community that molecules, such as water (H2O), consisted of collections of atoms (here, two hydrogen atoms and one oxygen atom).

Greek Origins of Nuclear Thought

Greek Origins of Nuclear Thought