Petroleum revenues continued to fuel Iran’s economy in the 1970s, and in 1973 Iran concluded a new 20-year oil agreement with the consortium of Western firms led by British Petroleum. This agreement gave direct control of Iranian oil fields to the government under the auspices of the NIOC and initiated a standard seller-buyer relationship between the NIOC and the oil companies. The shah was acutely aware of the danger of depending on a diminishing oil asset and pursued a policy of economic diversification. Iran had begun automobile production in the 1950s and by the early 1970s was exporting motor vehicles to Egypt and Yugoslavia. The government exploited the country’s copper reserves, and in 1972 Iran’s first steel mill began producing structural steel. Iran also invested heavily overseas and continued to press for barter agreements for the marketing of its petroleum and natural gas.This apparent success, however, veiled deep-seated problems. World monetary instability and fluctuations in Western oil consumption seriously threatened an economy that had been rapidly expanding since the early 1950s and that was still directed on a vast scale toward high-cost development programs and large military expenditures. A decade of extraordinary economic growth, heavy government spending, and a boom in oil prices led to high rates of inflation, and—despite an elevated level of employment, held artificially high by loans and credits—the buying power of Iranians and their overall standard of living stagnated. Prices skyrocketed as supply failed to keep up with demand, and a 1975 government-sponsored war on high prices resulted in arrests and fines of traders and manufacturers, injuring confidence in the market. The agricultural sector, poorly managed in the years since land reform, continued to decline in productivity (Source: Britanica).

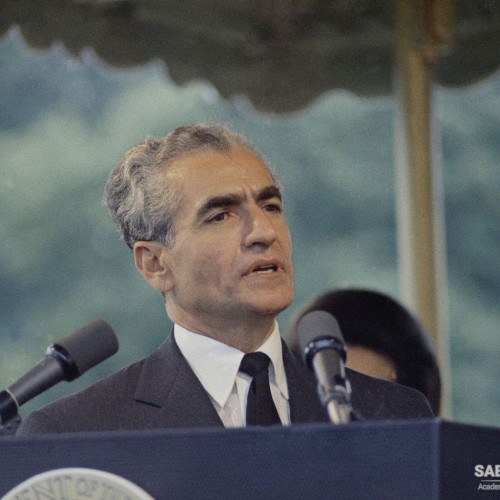

Shah, White Revolution and Covered Westernization of Iranian Society

Shah, White Revolution and Covered Westernization of Iranian Society