The modernization of Iranian music during the first Pahlavi era comprised certain attempts to free this music from its traditional form and content and bring it closer to the structure of European classical music. One can identify intellectual trends which must be considered as pro-Western rather than modernist, because their main objective was to fully eliminate Iranian music and replace it with European music. Also, regardless of the technical discussions about music and whether or not the Modernizers believed in the transformation of traditional forms of Iranian music, modernization represents certain thoughts that tried, by way of imitation from Western societies, to give a totally new definition of the place of music in Iranian society. In addition to pro-Western and modernist trends of thought, Iranian music in its then prevailing structure and form went through a natural evolution that was caused by the changing social conditions in Iran. The present study begins with reviewing the situation of Iranian music during the late Qajar period before the reign of Reza Shah, then discusses the modernization trends in Iranian music, and finally reflects on the degree of acceptance of these trends by the Iranian society at large during the Reza Shah period.

In any review of Iranian music during the Qajar period, the Constitutional Revolution is invariably considered as a defining moment:1 one of the causes of this revolution was Iranian society’s growing contact and acquaintance with Western ideas, which was accelerated by the revolution itself and influenced all social and cultural aspects of Iranian society. Thus, at this point, we shall review Iranian music during the Qajar period and post–Constitutional Revolution period. Iranian music during the Qajar period can be classified into the following categories: 1 motrebi music 2 classical music 3 religious music 4 military marches. Motrebi music was a kind of urban folk music during the Qajar period that was specially used in popular rites and festivities. It used to be played in groups and was accompanied by dances. Musicians playing in such groups were called the motrebs.

Since men and women attended separately held festivals, we find distinct motrebi bands consisting of either men or women in this genre of music. During the Qajar period, the women’s motrebi bands were always greater in number and enjoyed a much higher prestige than the men’s bands.2 They could perform in privately held women’s festivities, harem celebrations, and even in the presence of the shah. Men’s bands could only perform in men’s private parties and certain other public ceremonies. A limited amount of information on these bands can be found in travelogues of foreigners visiting Iran during the Qajar period.

Eugène Flandin, the French traveller, describes how a men’s motrebi band performed during his visit: Very wealthy Iranians have two-three motrebs perform while having lunch. One member of the band is a vocalist, who sings uninterruptedly in praise of love, wine, and gallantry. … [T]he concert played with their instruments does not produce a melodious sound. Iranian music is far behind what one could expect, mainly for two reasons: Firstly, it is scientific rather that imitative; secondly, it is being used by ordinary and common people who can’t do anything else; that’s why it has not been given the value and place it deserves. There’re quite few people who figure out what the music means and how it is played.

The classical-music musicians constitute another category of musicians who, contrary to motrebs, in most cases performed as solo players. These musicians used to play on occasions other than festivities and ceremonials, among which one might mention the private performance of music for the shah before he went to bed, as well as private gatherings of the elite groups. These musicians enjoyed a comparatively higher reputation than the lessrespected motrebs. 5 The classical musicians played a quite significant role in the protection and maintenance of the repertoire of the Iranian classical music (radif), which in its existing form mainly results from their activities during the reign of the Qajar dynasty.

The third category of musicians was mainly performing in the genre of religious music, playing different types of music according to the respective ceremony such as ta‘ziyeh (the Iranian passion play), nowheh (lamentation), rowzeh (sermons), monajat (prayers to God), and azan (call to prayers). Religious music in Iran was generally a vocal music, since in the Shi‘ite clergy singing was not considered as religiously forbidden (haram) and was therefore much more respected than instrumental music, which was regarded as haram. During the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries most Iranian singers had experience in the genre of religious music and were not considered as musicians in the eyes of the society; therefore, the term motreb was not used in reference to them. This provided an appropriate context for the protection and promotion of Iranian music, because the singers, active in this field, were fully familiar with the structure of Iranian classical music.

Another group of musicians that was active played military marches. The first phase of modernization of Iranian music took place in this field and was marked by the establishment of a Military March Department (Sho‘beh-ye Muzik) at the Dar al-Fonun school in 1868.6 Since the military march was taught in its Western form by a French officer named Alfred Jean Baptiste Lemaire, the Dar al-Fonun served as a stepping stone for the acquaintance of Iranian students with the theory of Western music and the introduction of certain Western instruments to Iran.

An outstanding effect of the Dar al-Fonun was the introduction and circulation of the French term musique in Iranian society as a substitute for the traditional expression of the naqqareh khaneh (the kettle-drum band) music, which was in use until the 1870s. Accordingly, those performing musique were labelled as muzikchi-ha (musicians) and local musicians, in contrast, as motrebs. In fact, all musicians active in the field of motrebi music as well as the classical-music performers were called the motrebs in the society at large.

During the reign of Naser al-Din Shah Qajar the division between ‘amaleh-ye tarab for the motrebs and ‘amaleh-ye tarab-e khasseh for the classical musicians was consolidated, and the terms served as a sort of evaluation of the two categories, since the ‘amaleh-ye tarab-e khasseh received a much higher degree of respect at the royal court. However, to what extent this distinction was common within Iranian society is doubtful. Hence, those members of the upper classes who decided to learn the art of music usually kept it secret.

Upon becoming familiarized with the theory of Western music, students of the Dar al-Fonun tried to apply what they had learnt to Iranian music. Hoseyn Heng Afarin, one of these students, began to transcribe the Iranian classical-music repertoire, based on the performance of Mirza ‘Abdollah, a celebrated setar player of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries in the field of classical music. Within the abovementioned four categories of music during the Qajar period, the introduction of military music in its Western form represents the beginning of the modernization of Iranian music, which entered the next phase simultaneously with the Constitutional Revolution.

The most significant event in the history of Iranian music during the pre– and post–Constitutional Revolution era was the effort of musicians to separate from performing at the royal court. There are numerous examples of such attempts: Darvish Khan, for instance, a popular tar player during the first decades of the twentieth century, sought asylum in the British Embassy in Tehran to find release from the duty of serving Mozaffar al-Din Shah’s son.10 The musicians were able to leave the royal court service due to the development of a new economic basis produced by changing social conditions during the twentieth century. These new social conditions, such as the influence of the growing Iranian middle class, were among the most effective factors in the formation of the Constitutional Revolution itself.

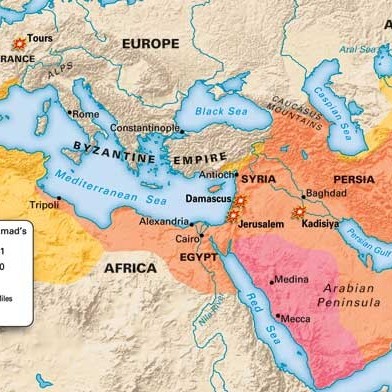

The Expansion of Islam in Various World Regions

The Expansion of Islam in Various World Regions