In 1319, during Abu Sa'id’s reign, Pope John XXII divided the Franciscan diocese of Khan Baliq (China), and created a new ecclesiastical seat in Sultaniya, to which he confided Western Asia, India and Ethiopia. The first incumbent was Francis of Perugia, who was granted six suffragans; he was followed by William Adam in 1323. There were Catholic bishoprics established in Tabriz, Maragha and Dehkhwarqan. The atmosphere of insecurity persuaded a group of Armenian monks to join Rome in 1319.

Knowing the benevolence of Amir Chupan towards Christians, the Pope wrote to him in 1321 to recommend his Franciscan missionaries and all the Christians residing in Persia. It appears that he listened to the Pope’s exhortations, at least to protect the Christian Armenians from their Muslim neighbours. But two years later, a definitive peace treaty was agreed between the Persian Khanate and Mamluk Egypt, and the political relations between Persia and the Latin states deteriorated, if they did not actually temporarily cease. By 1328, Barthelemy of Bologna was the only Catholic bishop left in Persia, in the town of Maragha. The Nestorians had lost so much of their influence and presence at the court that the ambassadors were henceforth chosen from the Italian merchants established in Iran, who had certainly acquired the local language, now making non-Iranian Christians ideal representatives.

One of the most important effects of the Mongol invasion was the ‘secularization’ of the cultural atmosphere in Iran. For the first time in centuries Islam was abolished as the official religion, and no other state religion was imposed. Consequently, not only were non-Muslims politically and socially emancipated, they were also culturally ‘demarginalized’. As Islam was not supported by the new rulers, its language, Arabic, lost its cultural dominance to Persian. The Mongols used Persian extensively in their diplomatic exchanges. Even the rulers of the Golden Horde sent letters in Persian to the sovereigns of other states besides those of Iran. The emergence of Persian as the language of art and science, although not falling directly within the scope of this study, had a notable impact on the non-Muslims and their participation in the new developing culture. Persian, unlike Arabic, did not challenge their tradition, as it had no religious value. Thus, it could be used without inhibition.

The first non-Muslim group to manifest itself in Dari Persian, appears to have been the Zoroastrians. During the 9th and 10th centuries, a series of Zoroastrian religious texts were produced in Pahlavi scripture, and one Zoroastrian author, Kay Kavus, even wrote his story in Classical Persian, but after the tenth century no Zoroastrian documents are preserved until the Mongol invasion. This scarcity of sources makes the evaluation of the Zoroastrians’ cultural activity difficult; nonetheless, some inferences maybe drawn from the works of Zarthusht Bahram, and his father Bahram Pajdu.

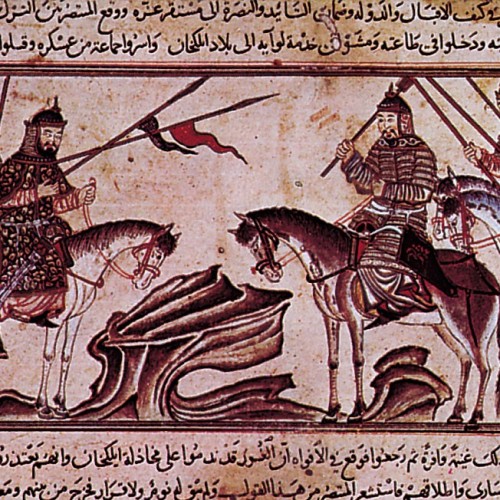

Mongol Invasion and Life Conditions of Religious Minorities in Mongol Persia

Mongol Invasion and Life Conditions of Religious Minorities in Mongol Persia