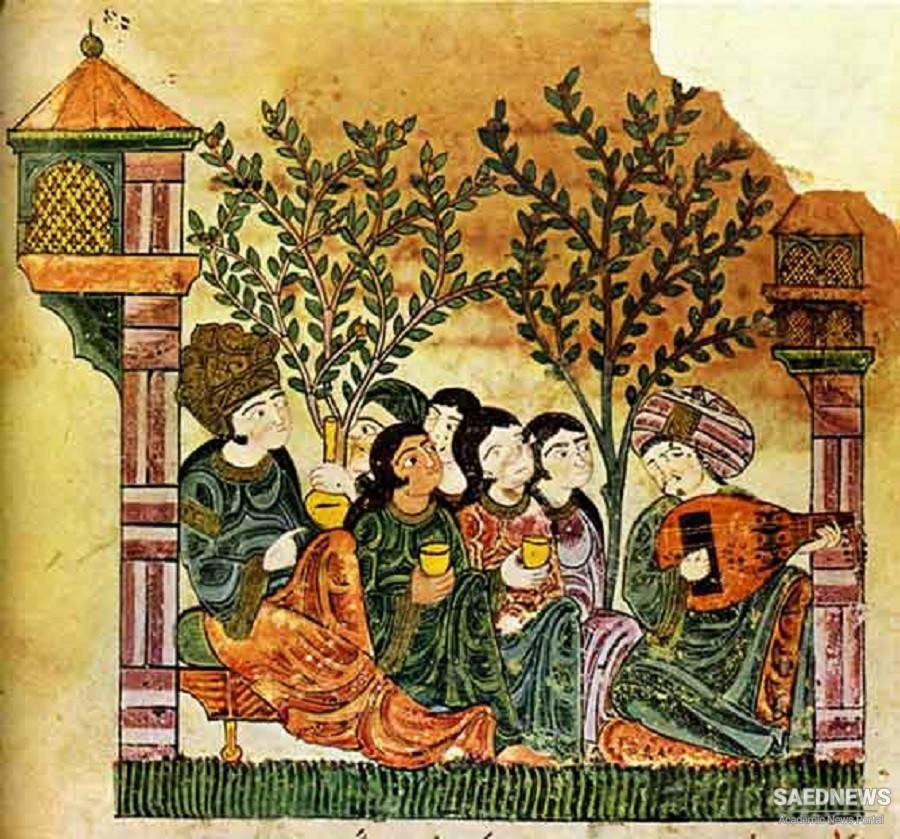

In these circumstances there can be no doubt that musical performance was important in Persia as well. Tradition does not report this very frequently, but mentions some Persian melodies (alḥān) from Fars and numerous musical instruments. Besides the lute | (ʿūd) and the dulcimer (ṣanj), of which the inhabitants of Khurasan had a particular version (muwannaj) with seven strings, much-loved instruments in Persia included the tambourine (tanābīr, also spelled ṭanābīr), barābīṭ, a lutewith a wooden box, and the flute (nāi; mizmār). In 743 the caliphs had musical instruments together with dulcimer players (ṣannāj) come from Khurasan to Damascus in order to have a complete band of musicians at court. When receiving allied princes101 and ambassadors, the Ghaznavids had their musicians play fiddles (rabāb[a]) and harps (chang), or beat on drums (duhl) and tambourines (dabdaba). Military triumphs were also celebrated with music, and there are reports that the soldiers of the Khurramite leader Bābak used a kind of oboe or flute to identify themselves. The Assassin prince Ḥasan-i Ṣabbāḥ (d. 1124) on the other hand was opposed to music, or at least to the playing of trumpets, perhaps for religious reasons. Music would maintain a particular rhythm (īqāʿat) and was recorded as a melody of notes. If a concert was being held, which was also recommended during feasts, there would be certain guidelines recommending a particular choice of songs to be performed (e.g. ‘now reunion, now separation – now faithfulness, now heartache’). Praising the Prophet and virtue as well as lamenting the vanity of the world were also among the subjects recommended for songs (Source: Iran in Early Islamic Period).

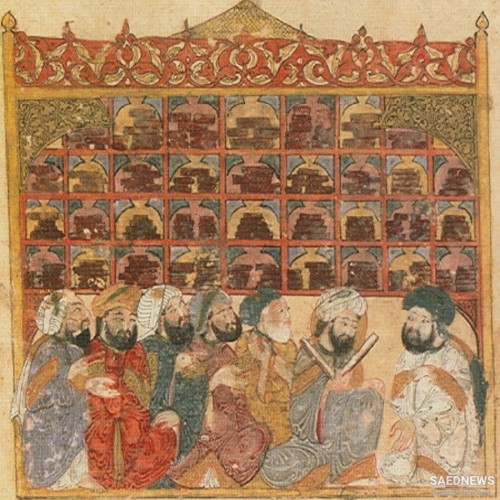

Intellectual Conversion of Persian Culture into Islamic Scholarship

Intellectual Conversion of Persian Culture into Islamic Scholarship