The coinage mashruteh in fact meant “conditional,” denoting the setting of conditions on the power of the sovereign. Borrowed from the neighboring Ottoman Empire’s first constitutional regime of 1876, which was aborted in 1878 by Sultan ‘Abd al-Hamid, meshrutiyet (as it pronounced in Ottoman Turkish) represented for the Iranians more than just the new conditional system; it represented the entire constitutional experience and political order it entailed. The term mashruteh, moreover, implies a familiar chapter on “conditions” (shorut) in Islamic law, which in turn gave it a certain Islamic acceptability and in the eyes of the ulama and the public put it at a safe distance from such alien notions as constitution and constitutionalism.

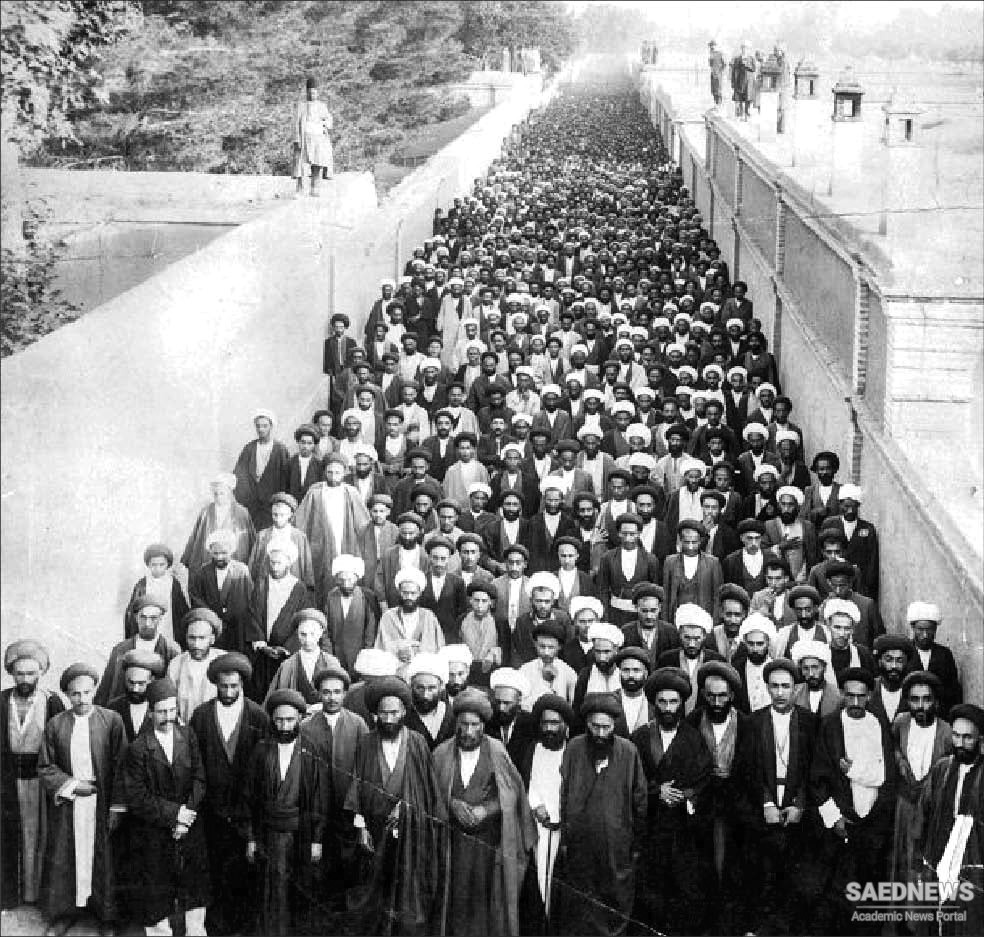

Public debate and publications further gave the term mashruteh and associated buzzwords a greater currency. The growing telegraphic communications throughout Iran’s major cities made it possible for protesters in the capital to transmit the constitutional message of the movement and to coordinate their efforts with cohorts in Tabriz, the true center of radical activism, and elsewhere. Thus, the movement was no longer seen as a quarrel between the ulama and the Qajar state; it had acquired a nationwide constituency that was increasingly becoming conscious of its message and its national identity. “Long live Iran!”—a rallying cry of the constitutionalists from the earliest days—touched on such patriotic sentiments.

As has often been noted, only a small number of the elite understood the idea of the constitution and the liberal values associated with it. Yet the Iranian public was quick to employ the term to air its resentment of their destitution, material decline, and the insecurities they faced in everyday life. For these ills, the people held the ruling establishment responsible. If notions of constitutional rights and democratic representation were new to them, poverty, decline, and state arbitrary rule were familiar. It is rather naive to blame the ordinary people, as critics of the Constitutional Revolution often have, for their unfamiliarity with the lofty liberal ideals of Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Montesquieu, or John Stuart Mill. It is even more condescending to expect that all revolutions would have a standard interpretation of modernity.

The sanctuary in Qom, protests in Tehran, and mediation between the mashruteh seekers and the royal court by moderate statesmen obligated the weary Qajar shah and his court officials to dismiss the unpopular premier, ‘Ayn al-Dowleh, whose draconian measures triggered the earliest protests. He was the third member of the Qajar tribe in a century to serve as premier and stir a crisis. Later, in 1908, his part in quashing the revolutionary resistance in Tabriz further blackened his image as a staunch reactionary. Shortly thereafter, the protesting ulama who had taken refuge in Qom returned after the shah only implicitly accepted their demands. Yet on August 10, 1906, under increased public pressure, he could see no other way but to issue a rescript that came to be known as the Constitutional Decree (Farman-e Mashrutiyat). Addressed to the new premier, Nasrollah Khan Moshir al-Dowleh, the receipt called for the establishment of a “national consultative assembly [majles-e showra-ye melli] . . . to carry out the requisite deliberations and investigations on all necessary subjects connected with important affairs of the state and empire and the public interests; and shall render the necessary help and assistance to our cabinet and ministers in such reforms as are designed to promote the happiness and wellbeing of Iran.”

Constitutional Aspirations and Shift in Regional Policies

Constitutional Aspirations and Shift in Regional Policies