So was the subsequent advance on Tabriz, which was plundered and laid in ruins, but not occupied. Shah Safi himself took part in the Persian counter-offensive in the following spring, which ended with the reconquest of Erivan. Overtures of peace made by the Persians immediately afterwards were once more unavailing.

The reason for the Supreme Porte's reluctance to make peace was no doubt that Istanbul had not given up the idea of reconquering Baghdad. In fact, in 1048/1638 the sultan again undertook a campaign into Mesopotamia, by means of which he achieved the desired result, for Baghdad fell into his hands in mid-Sha'ban/the closing days of December without the Persians making any attempt to relieve their garrison in the city. From then until the First World War the city remained an Ottoman possession.

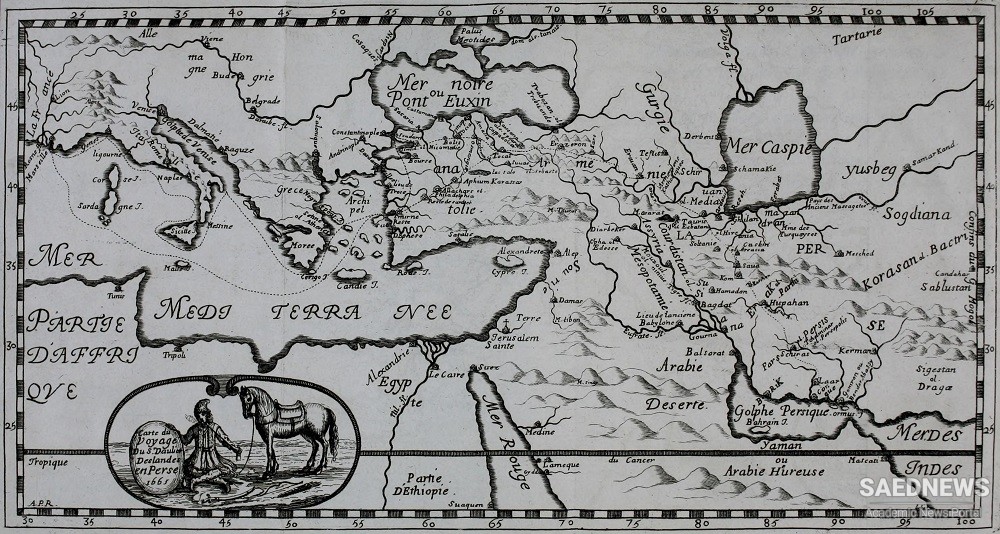

In spite of the atrocities that followed the conquest, the Persians entered into peace negotiations with the Ottomans. These resulted, on 14 Muharram 1049/17 May 1639 Peac e treaty of Zuhab, as a consequence of which a settlement of frontiers was agreed that survived beyond the end of the Safavid empire and — apart from the northern sector, where a new situation was created by the advance of the Tsarist empire in the 12th/18th century — endured up to the present time. For Persia, it meant not only the loss of Baghdad, but also the final abandonment of the whole of Mesopotamia. Both parties abided by the terms of the treaty, and after this no more wars were fought between the Safavids and the Ottomans.

Nor were there any serious consequences from conflicts in the Transcaucasian petty states, especially the Georgian kingdoms and principalities, where Safavid and Ottoman interests overlapped. It will be remembered that Shah 'Abbas I had not only undertaken campaigns of conquest into Georgia, but had transplanted very large numbers of Georgians to Persia, where many of them, in connection with the reorganisation of the army, were taken into the Iranian forces and not infrequently rose to the higher and even to the highest military and governmental positions. Stubbornly though the Georgians clung to their own national ways in their homeland, even under Muslim rule, to their language, and to their Christian faith especially, in Persia they were quickly assimilated and, alongside Iranians and Turks, formed the third ethnic element of modern Persian society. In this they contrasted markedly with their Armenian neighbours, whose treatment under Persian tutelage was entirely comparable.

Shah Safi's relations with Georgia have already been touched on in the context of the transfer of the governor of Isfahan, Rustam Khan. He held to the Islamic faith and had made his entire career in Persia up to this point; but in 1634 he succeeded in defeating Theimuraz and seizing power in Tiflis in the name of the shah. His success determined the lords of Imeretia, Mingrelia and Guria, who strictly owed allegiance to the Ottoman state and its ruler, to declare their willingness to accept the shah's authority.

Even Theimuraz, who at first disappeared from the scene, but later managed to oust the Safavid governor of Kakhetia, finally placed himself under the Isfahan government, which confirmed his rule over Kakhetia - clearly in order thus to create a rival to Rustam and prevent his gaining excessive power. Conflicts between the two viceroys, Rustam and Theimuraz, were not slow to develop, but did not assume very serious proportions. Thus Rustam Khan, who remained in office until his death in 1658, was able to give his country a long period of peace and reconstruction, of which it was sorely in need after the serious devastations and losses of population resulting from the campaigns of Shah 'Abbas I. The exportation of Georgians to Persia, especially boys and girls, continued throughout the nth/17th century, but it was no longer in the form of official, obligatory requisitions or forced deportations, as had formerly been the case, but was arranged by agents, who tackled the problem by means of bribes, persuasion, and cunning.

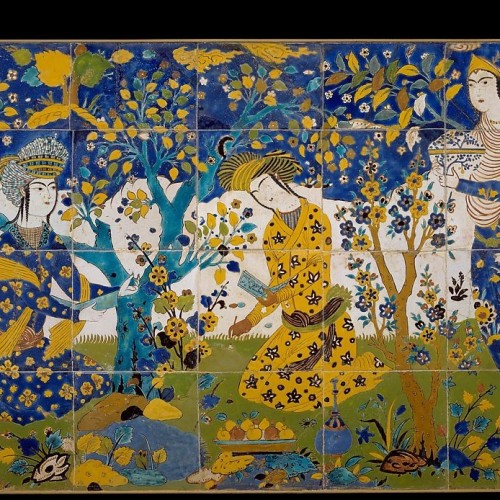

Royal Support of Art and Culture in Safavid Persia

Royal Support of Art and Culture in Safavid Persia