These judgments and ordinances were not revealed to the Prophet (s) in order for him and the Imāms (‘a) to convey them truthfully to the people as series of divinely appointed muftis,52 and then to pass this trust on in turn to the fuqahā, so that they might likewise convey them to the people without any distortion. The meaning of the expression: “The fuqahā are the trustees of the prophets (‘a)” is not that the fuqahā are the trustees simply with respect to the giving of juridical opinions. For in fact the most important function of the prophets (‘a) is the establishment of a just social system through the implementation of laws and ordinances (which is naturally accompanied by the exposition and dissemination of the divine teachings and beliefs). This emerges clearly from the following Qur’anic verse: “Verily We have sent our messengers with clear signs, and sent down with them the Book and the Balance, in order that men might live in equity” (57:25). The general purpose for the sending of prophets (‘a), then, is so that men’s lives may be ordered and arranged on the basis of just social relations and true humanity may be established among men. This is possible only by establishing government and implementing laws, whether this is accomplished by the prophet himself, as was the case with the Most Noble Messenger (s), or by the followers who come after him.

God Almighty says concerning the khums: “Know that of whatever booty you capture, a fifth belongs to God and His Messenger and to your kinsmen”(8:41). Concerning zakāt He says: “Levy a tax on their property”(9:103). There are also other divine commands concerning other forms of taxation. Now the Most Noble Messenger (s) had the duty not only of expounding these ordinances, but also of implementing them; just as he was to proclaim them to the people, he was also to put them into practice. He was to levy taxes, such as khums, zakāt and kharāj, and spend the resulting income for the benefit of the Muslims; establish justice among peoples and among the members of the community; implement the laws and protect the frontiers and independence of the country; and prevent anyone from misusing or embezzling the finances of the Islamic state.

Now God Almighty appointed the Most Noble Messenger (s) head of the community and made it a duty for men to obey him: “Obey God and obey the Messenger and the holders of authority from among you” (4:59). The purpose for this was not so that we would accept and conform to whatever judgment the Prophet (s) delivered. Conformity to the ordinances of religion is obedience to God; all activities that are conducted in accordance with divine ordinances, whether or not they are ritual functions, are a form of obedience to God. Following the Most Noble Messenger (s), then, is not conforming to divine ordinances; it is something else. Of course, obeying the Most Noble Messenger (s) is, in a certain sense, obeying God; we obey the Prophet (s) because God has commanded us to do so. But if, for example, the Prophet (s), in his capacity as leader and guide of Islamic society, orders everybody to join the army of Usāmah,53 so that no one has the right to hold back, it is the command of the Prophet (s), not the command of God. God has entrusted to him the task of government and command, and accordingly, in conformity with the interests of the Muslims, he arranges for the equipping and mobilization of the army, and appoints or dismisses governors and judges.

This being the case, the principle: “The fuqahā are the trustees of the prophets (‘a)” means that all of the tasks entrusted to the prophets (‘a) must also be fulfilled by the just fuqahā as a matter of duty. Justice, it is true; is a more comprehensive concept than trustworthiness and it is possible that someone may be trustworthy with respect to financial affairs, but not just in a more general sense.54 However, those designated in the principle: “The fuqahā are the trustees of the prophets (‘a)” are those who do not fail to observe any ordinances of the law, and who are pure and unsullied, as is implied by the conditional statement: “as long as they do not concern themselves with the illicit desires, pleasures, and wealth of this world” that is, as long as they do not sink into the morass of worldly ambition. If a faqīh has as his aim the accumulation of worldly wealth, he is longer just and cannot be the trustee of the Most Noble Messenger (‘a) and the executor of the ordinances of Islam. It is only the just fuqahā who may correctly implement the ordinances of Islam and firmly establish its institutions, executing the penal provisions of Islamic law and preserving the boundaries and territorial integrity of the Islamic homeland. In short, implementation of all laws relating to government devolves upon the fuqahā: the collection of khums, zakāt, sadaqah, jizyah, and kharāj and the expenditure of the money thus collected in accordance with the public interest; the implementation of the penal provisions of the law and the enactment of retribution (which must take place under the direct supervision of the ruler, failing which the next-of-kin of the murdered person has no authority to act); the guarding of the frontiers; and the securing of public order.

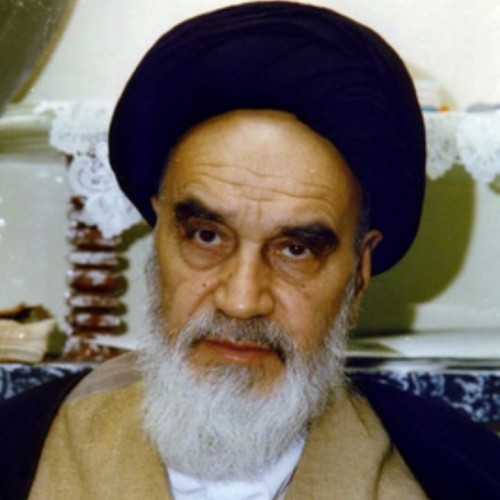

Imam Khomeini and the Revival of the Islamic Penal System

Imam Khomeini and the Revival of the Islamic Penal System