The highly artistic nature of Persians and their love for beauty, refinement, and delicacy enabled them not only to create one of the great schools of art in the ancient world associated with the Achaemenians, Parthians and Sassanids, but also to absorb and apply the principles of the Islamic revelation in the creation of numerous outstanding works of Islamic art. Both because of its richness, variety, and depth of expression, Persian Islamic art presents an ideal field for the study of the sacred art of Islam in relation to Islamic spirituality on the one hand and to the ethos and genius of a particular people and culture on the other.

Some of the principles of sacred art have already been discussed in earlier chapters but they need to be reasserted due to the confusion which reigns in the modern world as far as the nature of sacred and traditional art, as distinct from profane art, is concerned. To understand sacred art we must understand the meaning of the sacred and also the meaning of art, which today has become divorced from human life and relegated mostly to a few buildings called museums. To understand the sacred we must in turn comprehend the traditional view of reality, both cosmic and metacosmic, within whose confines men have lived and still continue to live in many Oriental countries.

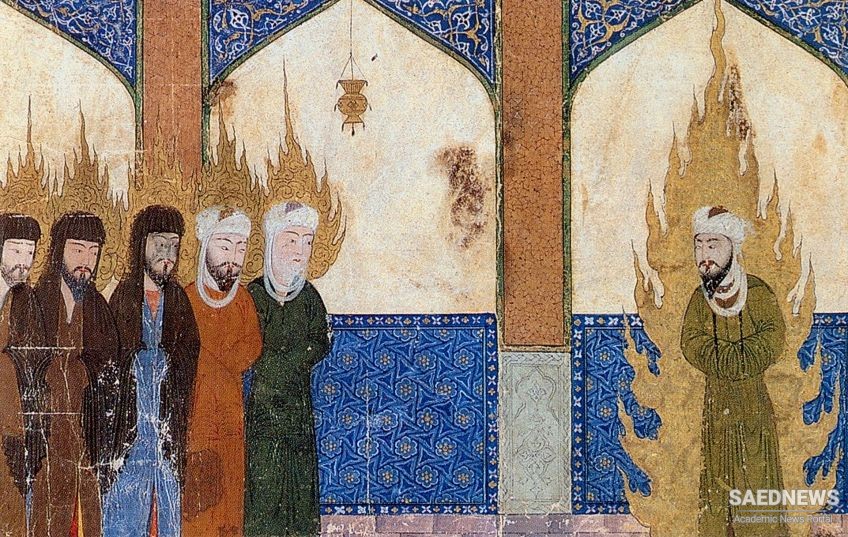

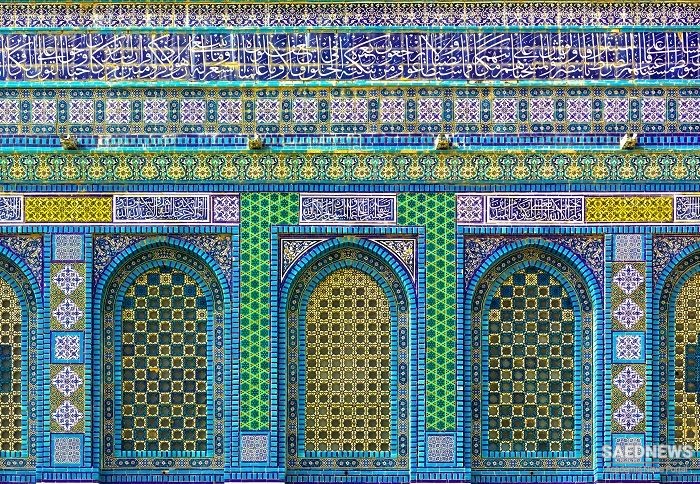

It is true that a religion can adopt certain forms and even artistic symbols of a previous religion, but in such a case the forms and symbols are completely transformed by the spirit of the new revelation, which gives a new life to them within its own universe of meaning. The techniques and forms of Roman architecture were adopted by Christian architecture to produce works of a very different spiritual quality. As we have already seen, Islam, and before it Byzantine Christianity, adopted Sassanid techniques of dome construction and produced domed structures which, however, reflect different types of art. In Persia itself Islamic art adopted many art motifs of pre-Islamic Persia with its immensely rich artistic heritage as well as those of Central Asia, but they became transformed by the spirit of Islam and served as building blocks in structures whose design was completely Islamic. The same could be said in fact about the Zoroastrian art of the Achaemenian Period which adopted certain Babylonian and Urartu techniques and forms but certainly transformed them into something distinctly Zoroastrian.

To understand sacred art and its efficacy in any context it is far from sufficient to search out the historical borrowing of forms. What is important is what forms and symbols mean within the traditional universe under consideration. And this question is unanswerable unless one has recourse to the religion which has brought the traditional civilization and sacred art into being. One could not understand, not to speak of create, works of sacred art without penetrating deeply into the religion which has produced these works. The attempt of some modern artists in both East and West to do so can be compared to trying to split the atom by copying the forms of mathematical signs found in books of physics. But as far as the result is concerned, it is the opposite, for any attempt to create such a so-called 'sacred art' must have severe repercussions in human terms.

Throughout Persian history an intimate relation has existed between art and the spiritual discipline deriving from the religion then dominant in Persia. Since little is known of the details of social organization in pre-Islamic Persia, the exact institutional link between the artisans and craftsmen and the priestly. Now, in the traditional view of the Universe in general and the Islamic universe in particular, reality is multistructured, that is, it possesses several levels of existence. It issues forth from the Origin or the One, from God, and it consists of many levels which, as mentioned in the previous chapter, in conjunction with Islamic cosmology, can be summarized as the angelic, psychic and physical worlds. Man lives in the material world but is at the same time surrounded by all of the higher levels of existence above it. Traditional man lives in the awareness of this reality even if its metaphysical and cosmological knowledge is beyond the ken of the 'ordinary believer' and reserved for the intellectual elite.

The sacred marks an eruption of the higher worlds within the psychic and material planes of existence, of eternity in the temporal order, of the Centre in the periphery. All that comes directly from the spiritual worldwhich stands above the psychic world and must never be confused with it, the one being ruh (spirit), and the other nafs (soul) in Islamic parlanceis sacred, as is all that serves as a vehicle for the return of man to the spiritual world. But this possibility, namely return to the realms beyond, is inseparable from the reality of the descent from above, because essentially only that which comes from the spiritual world can act as the vehicle to return to that world. The sacred, then, marks the 'miraculous' presence of the spiritual in the material, of Heaven on earth. It is an echo from Heaven to remind earthly man of his heavenly origin.

Although we have already mentioned the distinction between 'traditional' and 'sacred', it is necessary to return to this point in order to understand more clearly the role of sacred art in Persian culture in distinction from traditional Persian art. It must first of all be remembered that 'traditional' and 'sacred' are inseparable, but not identical. The quality termed 'traditional' pertains to all the manifestations of a traditional civilization reflecting the spiritual principles of that civilization both directly and indirectly. 'Sacred', however, especially as used in the case of art, must be reserved for those traditional manifestations which are directly connected with the spiritual principles in question, hence with religious and initiatic rites and acts possessing a sacred subject and a symbolism of a class is difficult to delineate. But the results are there to prove that such a link clearly existed. Nearly all important remnants of the art of that period are either religious or royal in character. And since the royalty was of a definite religious character, the royal art was in turn intimately connected with the Zoroastrian world-view. Even Persepolis, as has been suggested by A. U. Pope, seems to have been constructed as a palace for religious ceremonies rather than for the purely political activity of ruling over the empire. 3 Moreover, the architectural forms and the gardens have a definite traditional and symbolic character, the garden being a form of mandala which closes upon an inner centre and serves as a 'reminder' and 'copy' of paradise. It must not be forgotten that the word paradise itself, in European languages, as well as firdaws in Arabic, derive from the Avestan pairi-daeza, meaning garden, which itself was the terrestrial image of the celestial garden of paradise.

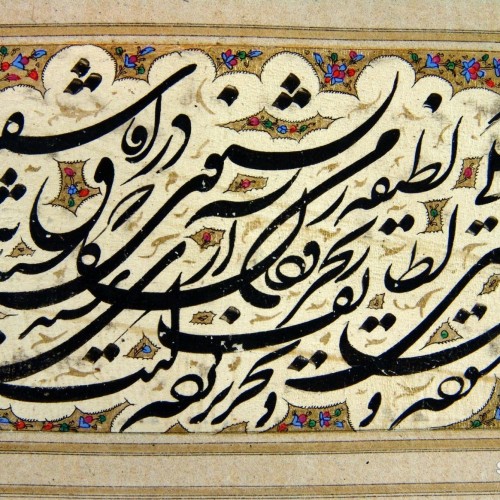

The Spiritual Message of Islamic Calligraphy

The Spiritual Message of Islamic Calligraphy