In such a religious country as Persia, and especially at this intensely religious time, what the clergy ordained and the royal court sanctioned was closely followed. Music lost its social approval, a condition that lasted well into the twentieth century. But even more damaging than the accompanying loss of patronage was its loss of respectability as a profession. In Safavid Persia, music became the province of illiterate entertainers, who were accorded the rank of laborer and in contemporary accounts are even called "laborers of pleasure." Among the upper classes, those with musical talent who might otherwise have become professionals remained amateurs, practicing their art in private. Indeed, the Safavid rulers so thoroughly suppressed the musical profession that even after the dynasty was firmly established and religious control relaxed, social disapproval of music remained,in marked contrast to the honoring of musicians in Sassanian times and to the great respect the musical profession held during the early Islamic period. Today, a legacy of the Safavid attitude can be discerned in the lesser respect accorded to music practice as compared with theory—in the prevalent attitude that "music is good when it is scientific, but playing is not good." This theme is also found in many present-day writings that mourn the loss of science in music with the passing of Safi al-Din in the thirteenth century, or Maraghi in the fifteenth, and declare the following centuries to be a dark age in Persian music until Vaziri reestablished Persian music on a scientific basis in 1923 (Source: Classic Persian Music).

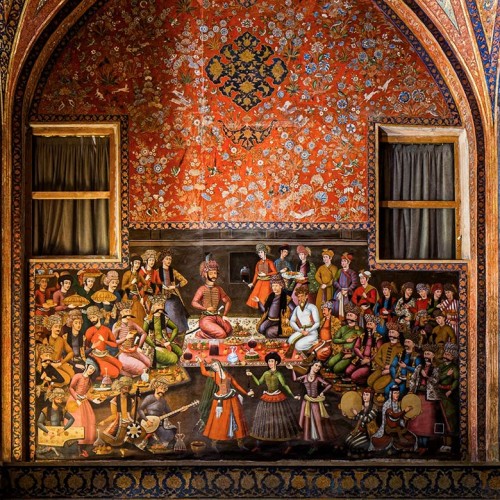

Renaissance of Classic Music in Safavid Persia

Renaissance of Classic Music in Safavid Persia