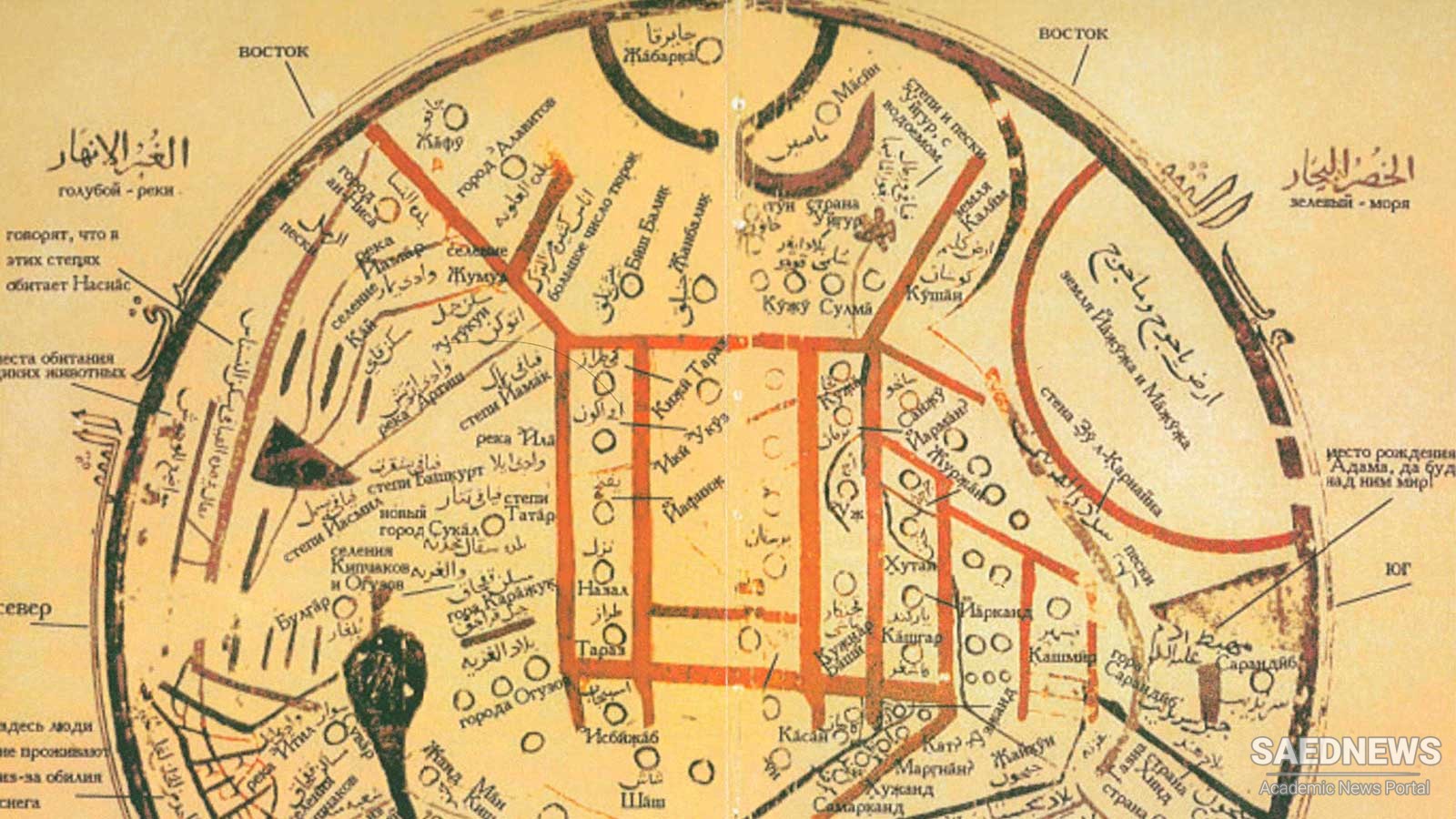

The first was a sudden and comprehensive change in the medium in which it was written, with the introduction of a specially adapted form of the Latin alphabet in 1928, accompanied by a total prohibition on any further use of the Arabic script for teaching or publication in Turkish. The second affected the substance of the language itself, particularly its lexicon, and comprised a systematic campaign, launched by the official Turkish Language Foundation in 1932, to ‘liberate’ Turkish from its ‘subjugation’ to other languages, i.e. to Arabic and Persian. In order to give some indication of the significance of this change it will be necessary to say something about the Ottoman form of Turkish, the precursor of the modern language. As a linguistic term, ‘Ottoman’ denotes the form of Turkic which became the official and literary language of the Ottoman Empire (1300–1922). This was, essentially, the variety of Oghuz Turkic which developed in Anatolia after that region was settled by Oghuz Turks in the eleventh to thirteenth centuries. It was written in the Arabic script, the form of writing adopted not only by the Oghuz but by all the Turkic-speaking peoples who, from about the tenth century onwards, had accepted the Islamic faith. The primacy accorded in Islam to the Arabic language itself, the language of the Qur’an, had a profound impact on the intellectual life of Ottoman society. The language of scholarship and of Islamic law, and the medium of instruction in the only schools available to the Muslim population before the nineteenth century, the medreses, was Arabic. In literature, on the other hand, the influence that was more directly felt was that of Persian, since it was the aesthetics of Persian poetry and ornate prose that provided inspiration for the Ottoman literati. A truly cultured Ottoman was expected to have a fluent command of ‘the three languages’, and many Turkish-speaking Ottomans did indeed write treatises in Arabic and/or poetry in Persian.

Turkish the Language and Its History

Turkish the Language and Its History