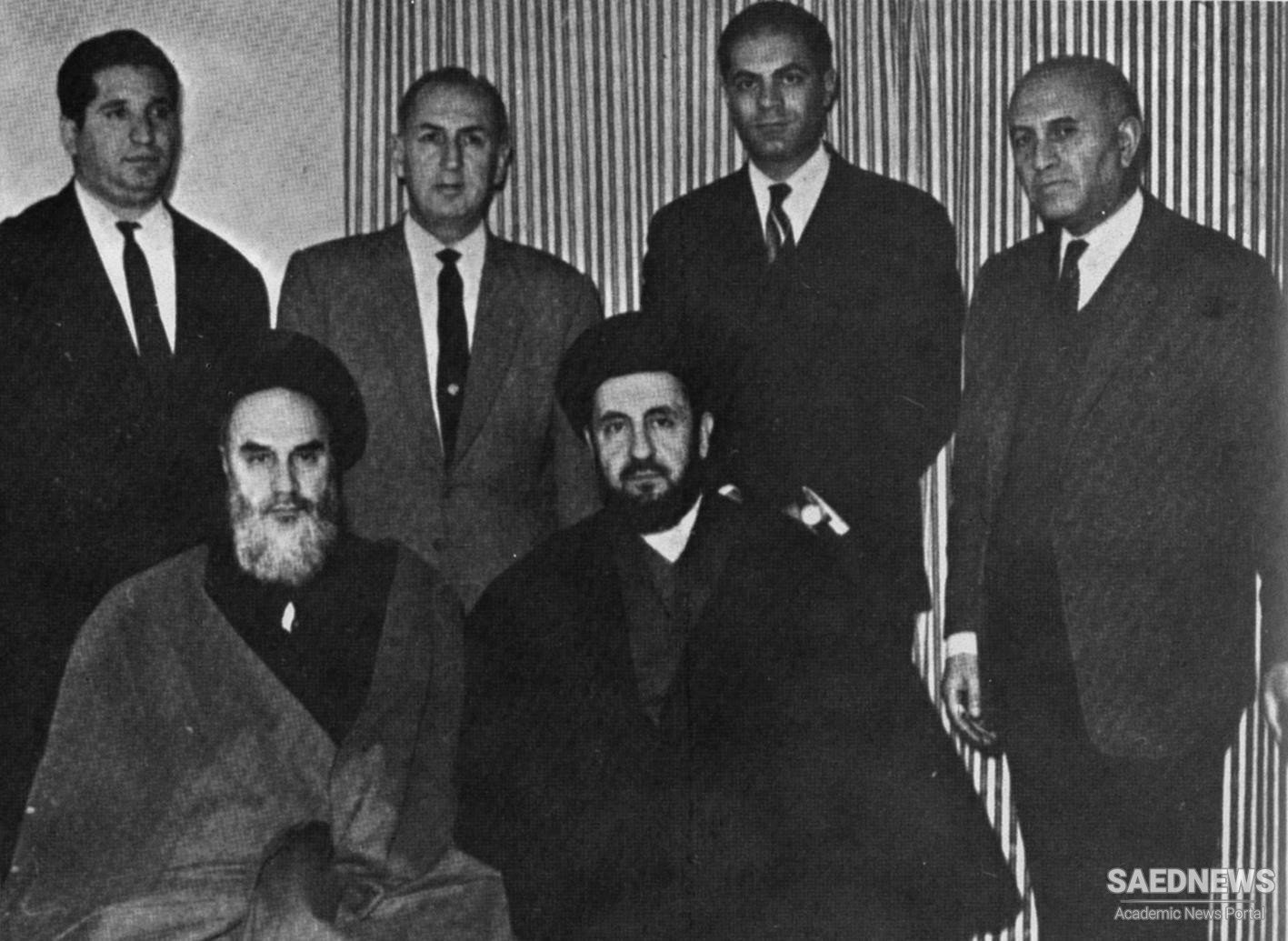

In 1963 a relatively obscure member of the ulama named Ruhollah Musavi Khomeini—a professor of philosophy at the Fayẕiyyeh Madrasah in Qom who was accorded the honorific ayatollah—spoke out harshly against the White Revolution’s reforms. In response, the government sacked the school, killing several students, and arrested Khomeini. He was later exiled, arriving in Turkey, Iraq, and, eventually, France. During his years of exile, Khomeini stayed in intimate contact with his colleagues in Iran and completed his religio-political doctrine of velāyat-e faqīh (Persian: “governance of the jurist”), which provided the theoretical underpinnings for a Shiʿi Islamic state run by the clergy. Land reform, however, was soon in trouble. The government was unable to put in place a comprehensive support system and infrastructure that replaced the role of the landowner, who had previously provided tenants with all the basic necessities for farming. The result was a high failure rate for new farms and a subsequent flight of agricultural workers and farmers to the country’s major cities, particularly Tehrān, where a booming construction industry promised employment. The extended family, the traditional support system in Middle Eastern culture, deteriorated as increasing numbers of young Iranians crowded into the country’s largest cities, far from home and in search of work, only to be met by high prices, isolation, and poor living conditions (Source: Britanica).