Tools found in Ethiopia are the oldest which we have (about 2 ½ million years old) and they consist of stones crudely fashioned by striking flakes off pebbles to give them an edge. The pebbles seem often to have been carried purposefully and perhaps selectively to the site where they were prepared. Conscious creation of implements had begun. Simple pebble choppers of the same type from later times turn up all over the Old World of prehistory; about 1 million years ago, for example, they were in use in the Jordan valley. In Africa, therefore, begins the flow of what was to prove the biggest single body of evidence about prehistoric man and his precursors and the one which has provided most information about their distribution and cultures. A site at the Olduvai Gorge in Tanzania has provided the traces of the fi rst identifi ed building, a windbreak of stones which has been dated 1 . 9 million years ago, as well as evidence that its inhabitants were meat-eaters, in the form of bones smashed to enable the marrow and brains to be got at and eaten raw.

Olduvai prompts a tempting speculation. The bringing of stones and meat to the site combines with other evidence to suggest that the children of early hominins could not easily cling to their mother for long foraging expeditions as do the offspring of other primates. It may be that this is the first trace of the human institution of the home base. Among primates, only humans have them: places where females and children normally stay whileOlduvai prompts a tempting speculation. The bringing of stones and meat to the site combines with other evidence to suggest that the children of early hominins could not easily cling to their mother for long foraging expeditions as do the offspring of other primates. It may be that this is the first trace of the human institution of the home base. Among primates, only humans have them: places where females and children normally stay while the males search for food to bring back to them. Such a base also implies the shady outlines of sexual differentiation in economic roles. It might even register the achievement of some degree of forethought and planning, in that food was not devoured to gratify the immediate appetite on the spot where it was taken, but reserved for family consumption elsewhere. Whether hunting, as opposed to scavenging from carcasses (now known to have been done by australopithecines), took place is another question, but the meat of large animals was consumed at a very early date at Olduvai.

Yet such exciting evidence only provides tiny and isolated islands of hard fact. It cannot be presumed that the East African sites were necessarily typical of those which sheltered and made possible the emergence of humanity; we know about them only because conditions there allowed the survival and subsequent discovery of early hominin remains. Nor, though the evidence may incline that way, can we be sure that any of these hominins is a direct ancestor of humanity; they may all be precursors. What can be said is that these creatures show remarkable evolutionary effi ciency in the creative manner we associate with human beings, and suggest the uselessness of categories such as ape-men (or men-apes) – and that few scholars would now be prepared to say categorically that we are not directly descended from Homo habilis , the species fi rst identified with tool-using.

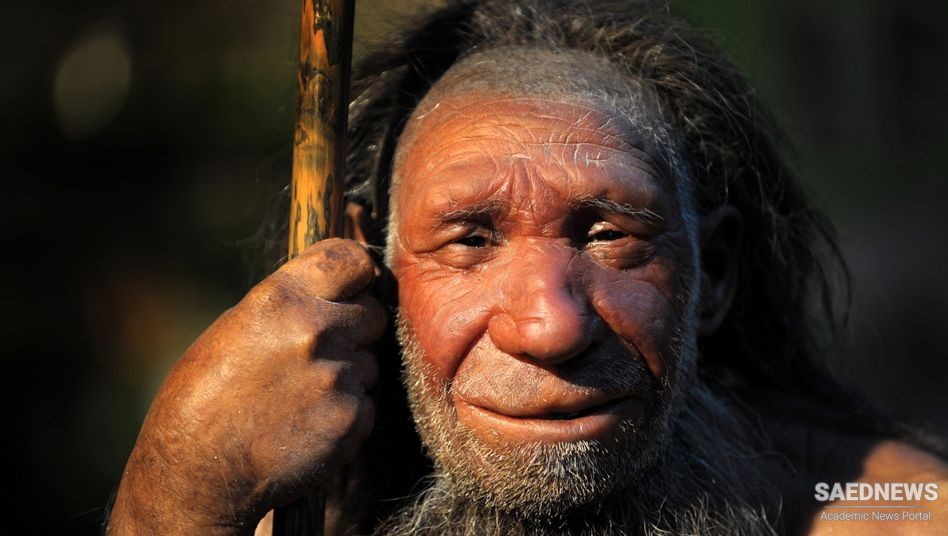

From Pithecus to Anthropos: Evolution of Homo Sapiens

From Pithecus to Anthropos: Evolution of Homo Sapiens