Suspected of Babi affiliation (even though they most likely were both agnostics), they were easy and legitimate prey, used to instill terror in the hearts of the public. The other revolutionary preacher, Jamal al-Din Isfahani, another Babi suspect who had fled the capital, was captured in the western town of Borujerd and swiftly put to death by the governor of the province with the shah’s approval. Two other journalists were murdered in prison. The rest of the detainees, including the two mojtaheds, were gradually released and sent into exile, and a few were employed by the shah as go-betweens to the remnants of the Majles deputies. The newspapers were all closed down and the anjomans were declared illegal. Two royal announcements proclaimed that, with the removal of the heretics and agitators, the shah intended to restore the “correct” constitutional regime within three months.

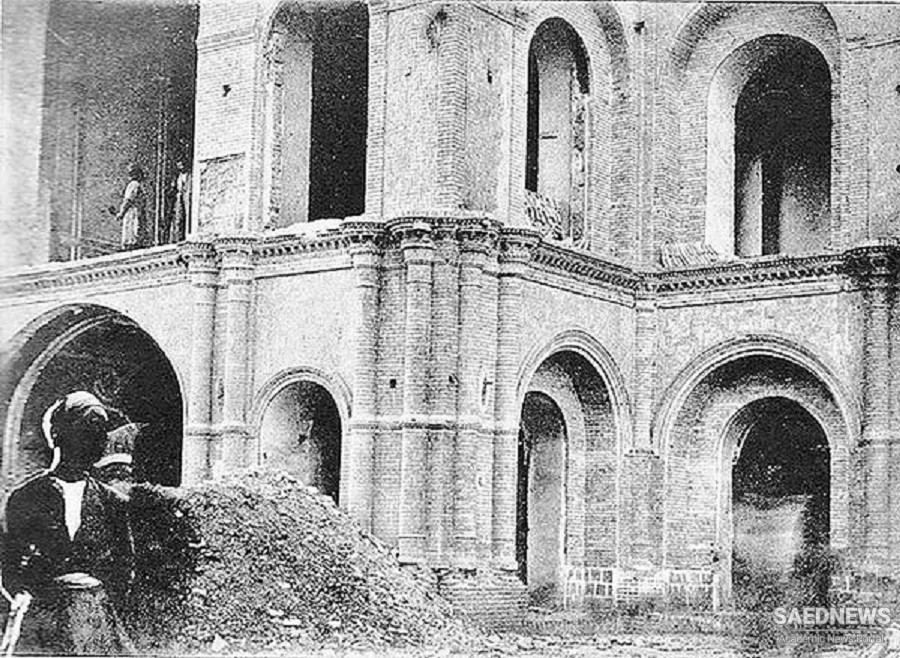

The royalist coup, the bombardment of the Majles, and the executions had the effect of terrorizing the public into silence, at least in the capital. People began to go about their business again, and the Tehran bazaar reopened with a sense of relief. With Nuri and his growing contingency of clergy fully integrated into the royalist camp and having abandoned for the most part their mashru‘eh objective in favor of Qajar absolutism, there were hopes that Mohammad ‘Ali Shah would consolidate his reign. Some sycophants among the Majles’ deputies began to ingratiate themselves with the shah, who liked to believe, at least for the sake of appearances, that he favored the constitutional regime. He declared, in conformity with Nuri’s propaganda, that he was against the prevalence of the radicals, heretics, and anarchists.

The royalists needed such rhetoric for domestic consumption but also to improve their tarnished image abroad. Although the coup was welcomed in St. Petersburg’s conservative circles, it was frowned upon in London and elsewhere. Save a handful of liberals in the Persia Committee—formed in October 1908 in support of the Iranian Constitutionalists—the European public was prepared to forget about Iran and its revolution. Most significantly, the great scholar and supporter of Iranian revolution Edward Granville Browne, protested the brutal clampdown in numerous pamphlets and newspaper articles. If it were not for the popular resistance that soon reignited in Tabriz and thereafter in Rasht and Isfahan, constitutionalism seemed to have lost.

There was also a sense of relief among the public, who hoped to see an end to chaos and a return to the relative calm and security of earlier decades. Growing harassment in towns and villages by plundering tribal horsemen and armed bandits, and encroaching Kurdish irregulars and Russian frontier guards in the northern provinces killed thousands and ravished the countryside. The Majles’ failure to deliver remedies to the country’s economic and social needs was an added source of public frustration. By the time of the coup, it was as though the whole mystique of the mashruteh had been spoiled, if not lost altogether.

Royal Coup against the Nascent Constitutional State

Royal Coup against the Nascent Constitutional State