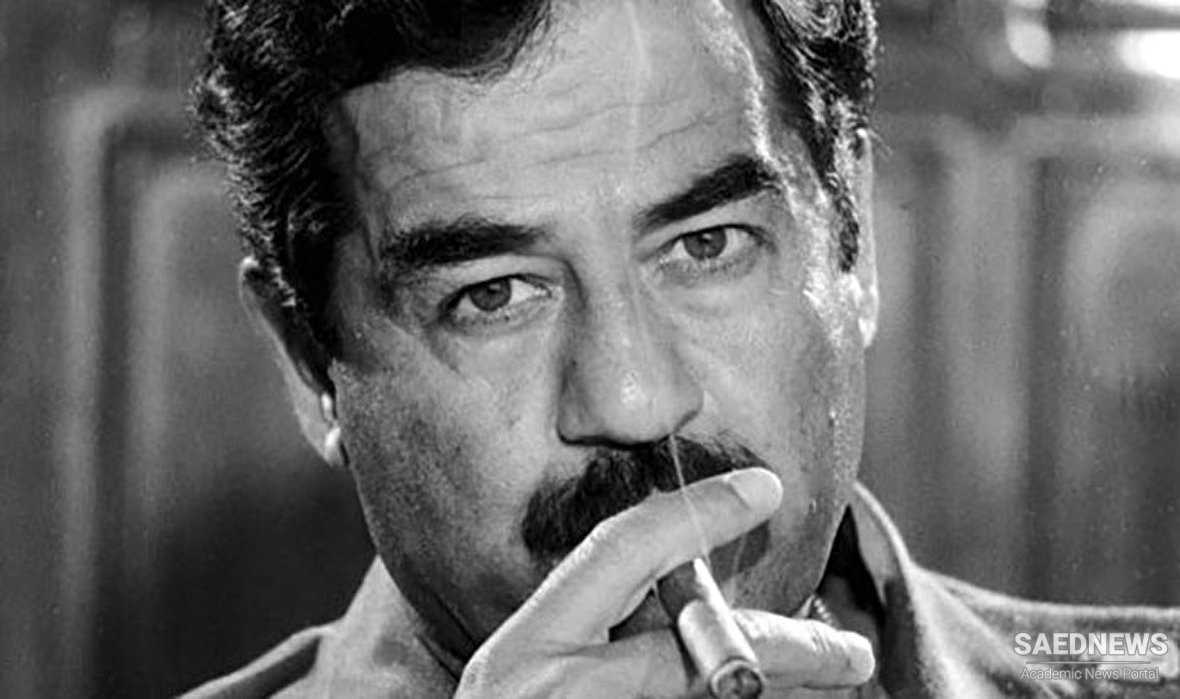

As the transition approached, the bosses apparently began maneuvering to block Saddam’s elevation. It is unclear precisely how they intended to accomplish this. Some observers have suggested that an issue was made of “party democracy.” Bakr and Saddam should not be permitted to orchestrate the succession; instead, the senior party leaders should have a say. Apparently there was to be a party congress at which Saddam’s candidacy would be voted upon.

There may well have been such a scheme, but we should not be swayed by the appeal to “democracy” into thinking that Saddam was bereft of intraparty support. In fact, he had a large following of junior party members who backed him against the older cadres. Saddam was a cautious individual who rarely made a move without preparing the ground. It is likely that he feared the outcome of a party congress vote that he could not sew up beforehand. This probably is what persuaded him to preempt the bosses by inducing Bakr to step down prematurely. Once installed as president, Saddam called for the creation of a national assembly—that is, a parliament—that would ratify his new office.

It was a fairly shrewd operation all around. By sanctioning the creation of a parliament, Saddam advanced Iraq toward modernization. By getting the parliament to legitimize his leadership, he circumvented the bosses’ attempt to cut him down. Of course his performance did not endear him to the bosses—and thus his next move. Saddam announced the discovery of a plot against himself, in which, he claimed, prominent party leaders were involved. We should not be surprised that all of the leaders implicated were suspected of being opponents of the new president. He subsequently ordered the execution of a number of them. And in a related move that was in many ways even more shocking, Saddam implicated Syria’s president Hafez el Assad in the alleged plot. As a consequence he aborted discussions then ongoing to form a union between Iraq and Syria, a plan promoted by Bakr over a period of years.

The Carrot and the Stick

The Carrot and the Stick