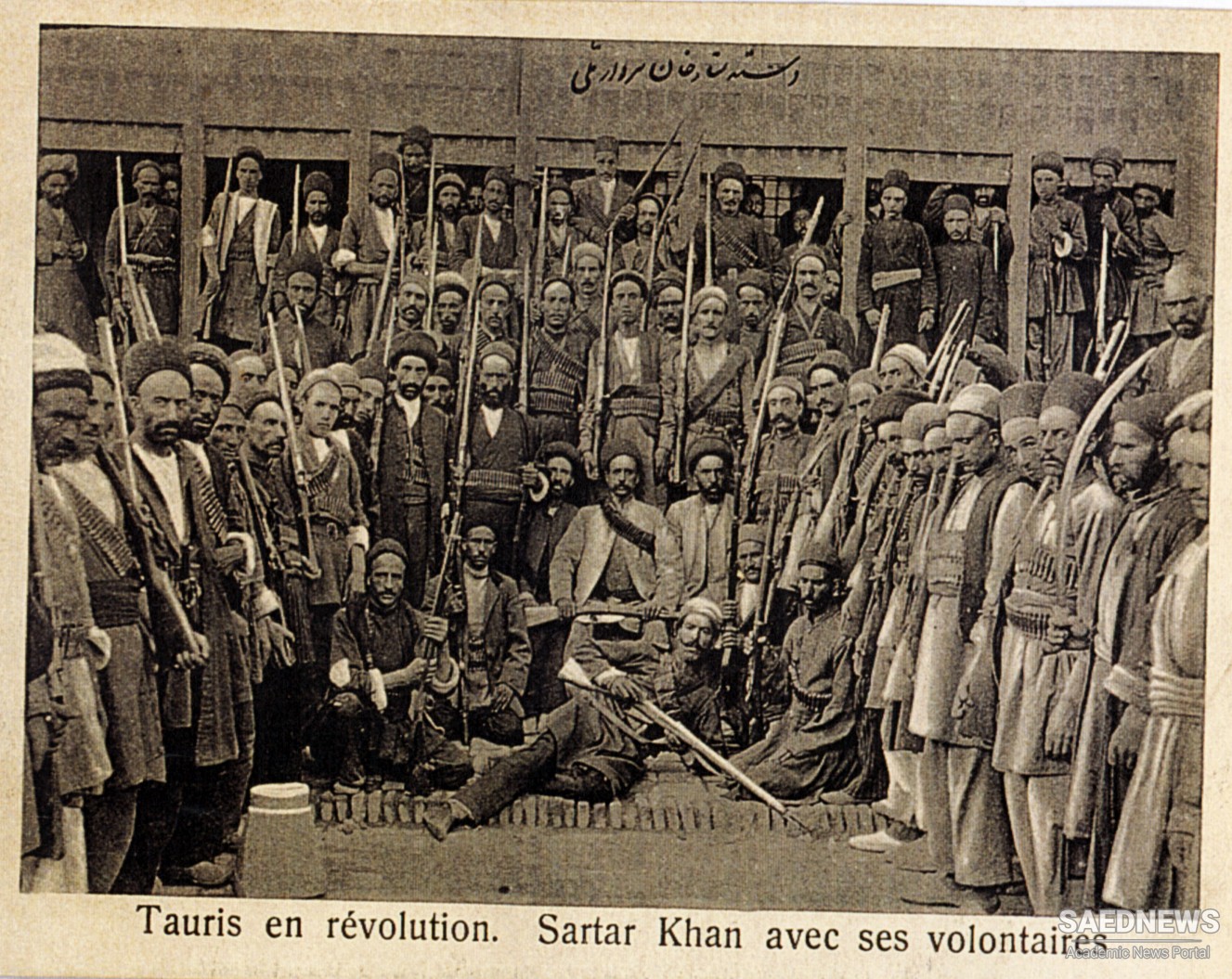

The radicals among the deputies and outside the Majles were supported by the revolutionary societies known as anjomans. Members of the anjomans, some of them armed with small weapons, assumed the task of guarding the Majles, but also acted as a pressure group, dictating their wishes to the legislature. Whether former Babis, nationalists, or socialists, the anjomans’ leadership came to play a decisive role in the political process. By mid-1908, there were at least seventy anjomans in Tehran alone, with an estimated five thousand armed fighters. Best known among them, Anjoman-e Azarbaijan, acted as a political party and a paramilitary force, and was the political agent for the influential provincial council in Tabriz known as Anjoman Ayalati Azarbaijan.

The mouthpiece of the constitutionalists and their supporting anjomans was the budding press, which had multiplied since 1905. They made explicit demands of the Majles, attacked the mashru‘eh camp and the court, and criticized the shah for not complying with his constitutional duties. By 1908, more than eighteen newspapers were in circulation all over Iran, as well as a vast number of tracts and clandestine posters. The journalists were of varying quality; some, like Mirza Jahangir Khan Shirazi (1870–1908), an intellectual from a Babi family, created the influential weekly Sur-e Esrafil (Seraphim’s trumpet) and set the tone for liberal constitutional debate with intelligent editorials.

The columns by a gifted satirist, Mirza ‘Ali Akbar Qazvini, with the pen name Dehkhoda (1879–1956), offered a vivid portrayal of revolutionary politics and current affairs through the eye of a witty Qazvini village headman. Other papers, particularly Habl al-Matin (Strong cord), published in Calcutta since 1893 under the editorship of Jalal al-Din Mo’ayyed al-Islam Kashani (1863–1930) and his daughter Fakhr al-Soltan (and during the constitutional period in Tehran and Rasht) placed Iranian constitutionalism in a broader regional context and amplified its international significance.

The thrust of most newspapers, however, focused on political education and advocacy of secular modernity, invariably tied up with emphasis on Iran’s window of opportunity to liberate itself from the slumber of centuries of ignorance and oppression by authoritarian institutions. The subtext was more drastic; it was as though between the lines they were calling for the removal of the old institutions: the Qajar kingship and the Shi‘i establishment and even a secular republican order. The passage of a press law in early 1908 that allowed for greater freedom of expression in turn brought more direct attacks on the shah and the royalists.

Beyond the press, the anjomans were successful in mobilizing not only the guilds and merchants of the bazaars but also a new class of government bureaucrats and even telegraph, post, and Tehran’s transportation workers. The state employees were willing to go on strike in support of the Majles. Remarkably, the Persian telegraph system, manned primarily by sympathizers of the constitutionalists, created under the government’s nose a semiclandestine communication network. The telegraphic network connected constitutionalists and their anjomans all over the country, thus allowing for the rapid exchange of ideas and decisions, calling on the Majles deputies to act quickly, and admonishing them for compromise and indecision. It reinforced a sense of national accord all over Iran from Tabriz and Rasht to Isfahan, Kerman, Shiraz, and Kermanshah.

Development of New Musical Structures in Qajar Persia

Development of New Musical Structures in Qajar Persia